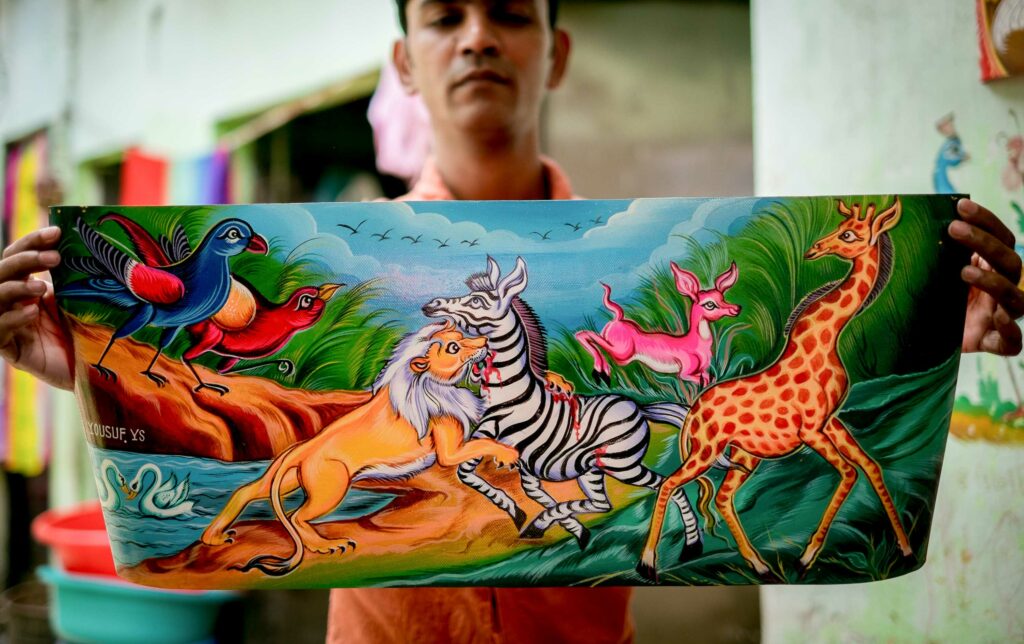

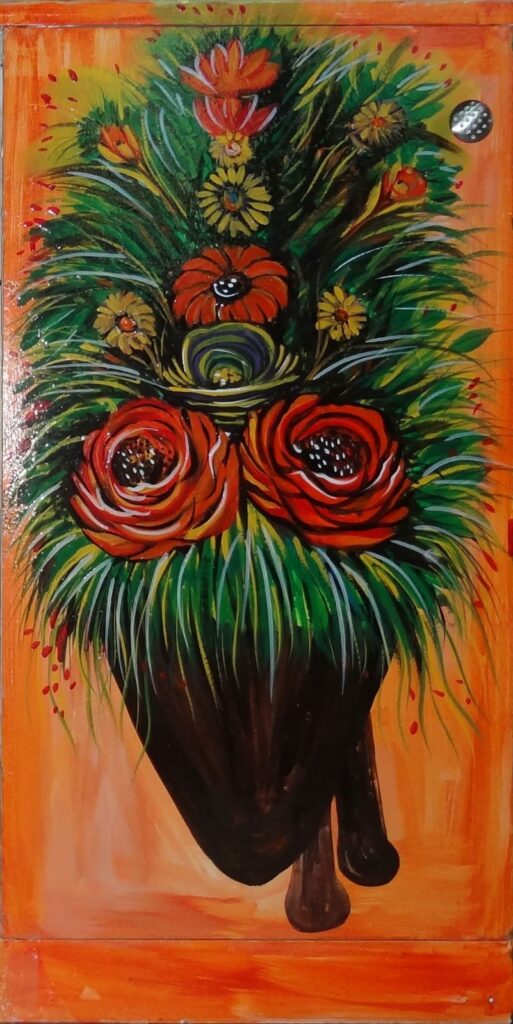

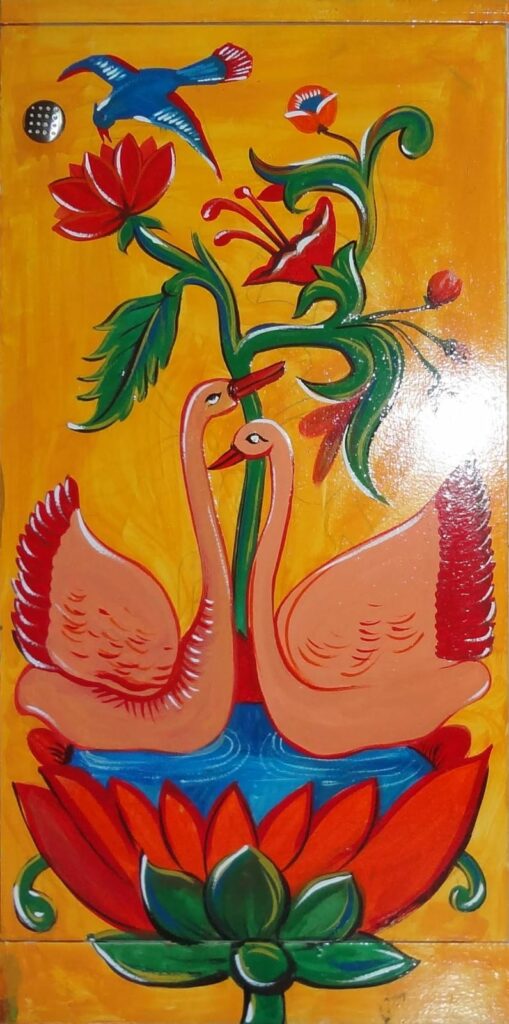

In December 2023 UNESCO inscribed Bangladeshi rickshaws and rickshaw decorative paintings on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. The colorful, hand painted, pedal driven carts used as taxis in the congested streets of Dhaka are considered the heartbeat of transportation in many parts of Bangladesh as well as in other Asian countries. They became the focus of favorable attention and recognition after the UNESCO proclamation brought back into light the artistry of the decorative oil paintings on the rear canvas and roofs of the vehicles, done by local artists who study with a master specializing in the craft of painting landscapes, portraits, abstract floral and animal decorations, sometimes movie stars and personal statements of the driver. Rickshaw decorative painting developed as an art form after the 1948 Partition of India, and is currently at risk of extinction as there isn’t a sufficient number of young people taking up this little rewarding traditional craft.

Here are some examples:

Fast forward to August 2024, nine months after the UNESCO declaration: the rickshaw is the again the focus of attention, this time in an outcry of rage and pain, when a family was able to recognize their slain son from a photo of his body dangling lifeless from a rickshaw. It was, in fact, this humble means of transportation that carried the body of 16 year old student Ghulam Nafiz to a hospital, after he was shot by the police during student demonstrations against the Sheikh Hasina’s regime on August 4. He was dead on arrival but the photo of his body on the rickshaw had circulated widely in the city and his parents recognized their dead son after two days of searching the whole city, having had no news of his whereabouts and no information from the police or the hospital administrators. The parents’ painful search was chronicled in an article of Dhaka most important daily, The Daily Star. Having become a symbol of resistance to the outrageous repression against the student led movement, initially demanding a reform of the quota system and later extended to large sectors of civil society against the Sheik Hasina regime, the image of the dead boy on the rickshaw multiplied to other forms of popular expression like graffiti, or more established art forms like oil paintings. On 19 August 2024, two advisers of the interim government and principal coordinators of Anti-discrimination Students Movement, Nahid Islam and Asif Mahmud, visited Nafiz’s home.Banani Bidyaniketan School and College named one of their academic buildings after him.The rickshaw carrying Nafiz was later donated to July Revolution Memorial Museum and the rickshaw puller, Nur Mohammad, was assured of financial assistance by the interim government.

In the photo to the left as well as in the graffiti and the oil painting there’s a contrast between the stillness of Ghulam Nafiz’s body and the rickshaw, the dynamic heartbeat of transportation in many parts of Bangladesh.

In the oil painting, to the right a mother reaches out, her hand resting on a painted canvas—a vibrant rickshaw now serving as a hearse for her son. Her fingers graze the painting of Ghulam Nafiz, his lifeless body lying still on the footrest of a rickshaw. What a contrast to this touching scene, the rickshaw’s showy vitality, it has now become an enduring symbol of Bangladesh’s summer of unrest. The piece of graffiti art depicted in the image in the center bears the words “The blood stain has not dried yet” and is part of a student-promoted graffiti campaign launched during the uprisings and in subsequent months, leading to many debates and soul searching in civil society.

The rickshaw, an omnipresent vehicle and a lifeline for millions in Bangladesh, is often decorated with kaleidoscopic designs that reflect the spirit of the streets. These designs are filled with organic motifs: lush flowers, spiraling vines, and in particular birds. Peacocks show off their vibrant feathers, swans their long necks, and roosters welcome a bright new day. These birds, painted in brilliant colors, evoke freedom, grace, and flight— the very freedom the students, much like Ghulam, sought. A stark contrast to his inert body.

For generations, rickshaws have been moving canvases, celebrating life and resilience. But on this occasion, the stillness of Nafiz’s body highlights a nation’s tipping point. The students who marched for freedom—freedom to dream, to dissent, to live without fear—were met with brutality. The orders, given by Sheikh Hasina herself. Their desire for liberation, like the painted birds, clashed against the harsh realities of government oppression. Among the material testimonials of rebellion and reminders of sacrifice, the rickshaw will stand as a symbol—not just of loss but of the vibrant hope for freedom that no repression could extinguish.

A student from Chittagong University Arts Department, Shakin Wahab has submitted photo images of rickshaw arts for the third photo gallery. We are grateful to writer Kazi Rafi, for suggesting and providing some of the images.

Melina Piccolo: I am a young woman embracing life’s journey, finding my path, and savoring each moment. Committed to growth and becoming my best self.

Pina Piccolo, founder and editor of The Dreaming Machine, is a writer and cultural activist both in the United States and in Italy.