A Postponement Obsolescence: Miyoshi Barosh Interview Conducted by Camilla Boemio

The art conversation, like any art, is a skill of focus on practices, topics and function of art. An in-depth conversation with the Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Miyoshi Barosh, who has an interest in the American socio-political underpinnings of culture. On the occasion of an excursus on obsolescence concept, I interviewed her. She articulates her passion for working in diverse media, her idea of being a cultural anthropologist and on the residual objects that have informed her practice.

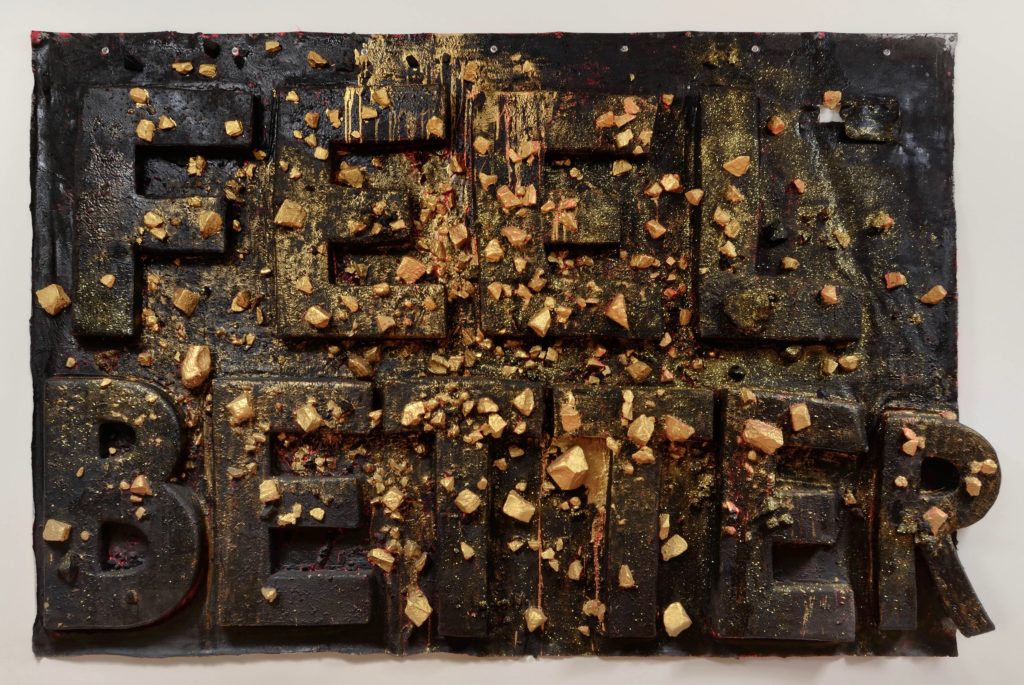

Based in Los Angeles, Barosh exhibited at the 2015 COLA (City of Los Angeles) Individual Artist Fellowship Exhibition at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. Her last solo gallery exhibition, FEEL BETTER, at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, was featured in Artbound, KCET’s culture blog, in January 2014. The title work, FEEL BETTER, was also the subject of a BOMB magazine Artist-on-Artist piece published in the 2013 fall issue. Other recent exhibitions include Body Conscious: Southern California Fiber at the Craft in America Center, Women, War, and Industry at the San Diego Museum of Art, and The Small Loop Show at the Fellows of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. She was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship last year. In 2017, she is participating in the Textile Biennale at the Rijswijk Museum (Holland) and is a visiting artist at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago.

Her work is centered on ideas concerned with cultural and individual “Failure” (the failure to make life better), Utopia, and Ruins. Materials such as fabric, glass, steel, Plexiglas, foam, fiberglass, paint, and found objects together with fabrics and yarn are used with both comic irony and heartfelt sincerity, pointing to both material and emotional excess. The uses of vernacular craft processes and folk traditions in combination with digital technologies contradict ideas about progress and technological determinism. While socio-economic questions are raised around ideas about authenticity, labor, and value in the use of craftwork, value is also seen as a projection of ourselves onto things, like cute animals on the Internet, mythic American landscapes, and the built environment.

CB: Your work references a lot of design ideas and history. You are also a great landscape designer. Can you introduce your background?

MB: The quick answer is that I went to the Rhode Island School of Design and then the California Institute of the Arts for graduate school. The combination of traditional art skills with a conceptual perspective defines my practice. I started out as a painter before becoming more of a sculptor, or what I call, genre-fluid. It took me a long time to find my subject. Leaving New York and moving to Los Angeles made a big difference.

I was born in Los Angeles but had a nomadic childhood that was like a cultural anthropologist’s crazy dream. Because my father worked for the US government as a geologist, we lived in various Western States and in Ankara, Turkey, and, finally, in the colonial suburbs of Boston. From visits to my mother’s Chinese family in Tokyo, to living in a trailer camp near Navajo reservations in the Nevada desert (engulfed in a radiation cloud from the 1963 hydrogen bomb test), to a summer spent living along a tributary of the Euphrates, and a summer driving through East Africa… This wide-ranging experience of the world made me an artist more than anything. It was imprinted on me that art is a cultural artifact (domestic crafts to religious icons) and defines our humanity.

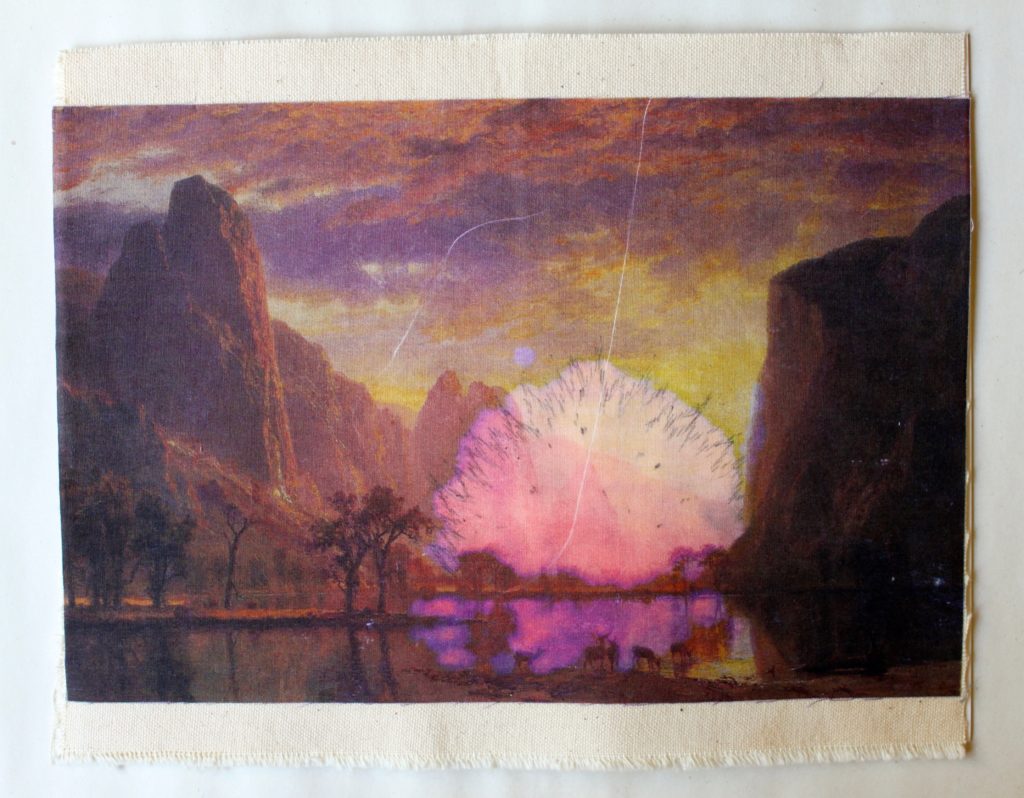

Landscape with Added Surprise and Impact #2, 2013, ink-jet print on fabric, graphite, and bleach, 6 ½ x 10 inches.

CB: Your use of myriad of materials such as: fabric, foam, fiberglass, paint and found objects, as well as craft processes are a refutation of ideas of progress. Acrylic yarns and thrift store purchased polyester knitwear are used with both comic irony and heartfelt sincerity as an Americanized Arte Povera. It’s an accumulation and assemblage in opposition to male dominated Modernism as well as a parody of aspirational consumerism. Tell me about your artistic practice.

MB: Accumulation and assemblage are strategies used in Pop Art that are alive and well today. As cultural critique, the tongue-in-cheek aspects of Pop Art in conjunction with Bakhtin’s concept of the Carnivalesque, create humor and chaos around established cultural and historical givens through that happy combination of irony and sincerity. Using cultural detritus, like used afghans or second-hand clothing, brings that kind of anthropological aspect to the art object that includes their modes of production. Human or machine labor (established signifiers of value) along with perceived aesthetic value become part of the narrative. Ideas about originality and authenticity are mocked while pointing to larger cultural failures that have to do with consumption and ecological disaster.

My current projects include other anthropological studies around failed social experiments, as well as to our increasingly neurotic relationship to meeting basic human needs.

Arcadia, 2013, burned and bleached fabric, ink-jet printed fabric, polyester and cotton batting, vinyl vacuum-formed acrylic letters and fiberglass, 78 x 118 x 7 inches.

CB: Could you talk about the temporal aspect and its value in formulating the work?

MB: In addition to the anthropological aspect of the materials, the “used” or “discarded” objects are capitalism’s detritus in the ever-churning production of the next, slightly better new thing. The psychological effect is anxiety, the possible loss of status if your choices don’t conform to hierarchical standards. The industrially produced objects have built-in obsolescence and reflect the failure of the Industrial Revolution (capitalist and communist) to make every life better. The handmade can still find redemption in that peculiar space where labor isn’t necessarily linked to value. The love-object, as Mike Kelley called it, still functions through emotional rather than monetary exchange.

The value of the re-purposed artifact–afghans, clothing, quilts–becomes again re-purposed, or in psychological terms, re-framed as objects of value through the process of abstraction: taken from one context and put in the context of the art object. Value has become increasingly abstract, just look at our globalized monetary system.

This abstraction of value and the attendant emotional anxiety creates a nostalgic longing for the older, moral narratives of accomplishment and perseverance. That sense of loss and longing emanate from discarded objects.

FEEL BETTER, 2012, acrylic, oil, glitter, high-density and upholstery foam on canvas, 93 x 132 x 7 inches.

The sense of failure, or worthlessness, inherent in the discarded is also present in ruins, real or metaphorical. While things are discarded in order to “upgrade,” ruins have been acted upon–destroyed or neglected. I wonder if we are experiencing a civilization on the brink of ruin… if we are also internalizing the sense of failure from the larger culture.

CB: Some art practices enable to extended the audience in different directions, towards new horizons, by moving freely on the margins, without following any set route, It can reach remote areas where art exist not only outside of the processes where they are commonly expected to be embedded like a fair or a museum.

To operate in this direction means to create awareness and an opposition that exceed the limits set by ‘high art’ – categories/concepts and their restraints/expectations, which are there to bestow authenticity and value on an individual work of art. Tell me a code for decoding on different directions.

MB: The increasingly fluid categories in the art world reflect the larger culture where hierarchies seem a lot less stable maybe because of the speed of communication and the abstract quality of our lives on social media, insurgent populism, and international terrorism. Pop art historically challenged notions of institutional hierarchy; the difficulty is that those institutions are losing their footing, categories and rules no longer exist, and we are all failing to separate illusion from reality. It appears, however, that the art world still clings to that archaic value system based on institutional legitimization as a place where abstract values can take form

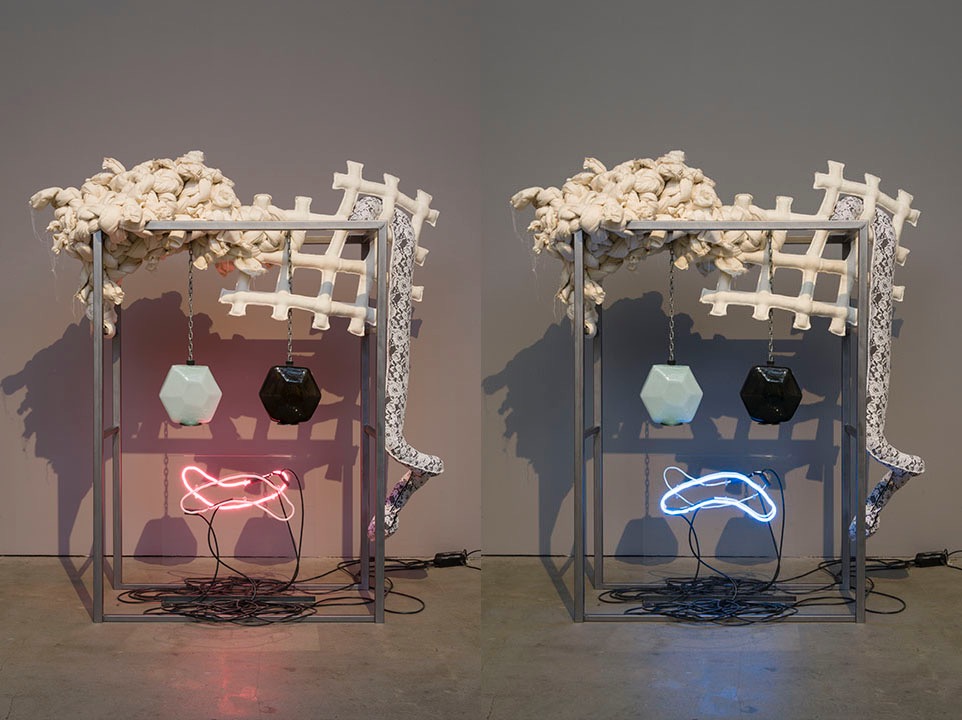

Receiving/Leaving, 2015, steel, glass, Plexiglas, neon, fabric, 84 x 56 x 28 inches.

CB: In a past conversation you stated that you are a big fan of historical perspective and think that most of problems are rooted in an historical amnesia. You agree that no matter how digitalized our futures become, humans have a need to make things by hand. Tell me more.

MB: As categories break down and technology forces us to work faster and produce more while internalizing institutional failures, I feel that many of us are suffering from a series of small mental breakdowns. The proliferation of mindfulness classes and meditation groups signifies this desire to slow down, but even then, they become items on a to-do list and just another networking opportunity.

To take the time to create something by hand is an ancient form of mindfulness and was part of religious “work” where labor represented redemption and spiritual release. The handmade object could once again take on that spiritual resonance from concentrated effort made without contemporary technology or technological interruption (no text, voice, email, no pings or whistles from cell phones).

To circle back to the first question, gardening is also a therapeutic experience/mindfulness exercise. Historical amnesia is present in all our socially constructed spaces including our Southern California “native” gardens. But an artificially constructed “natural” eco-system may be the best we can do now.

Soft Intervention, 2011, found afghans and polyfill, 60 x 48 x 22 inches.

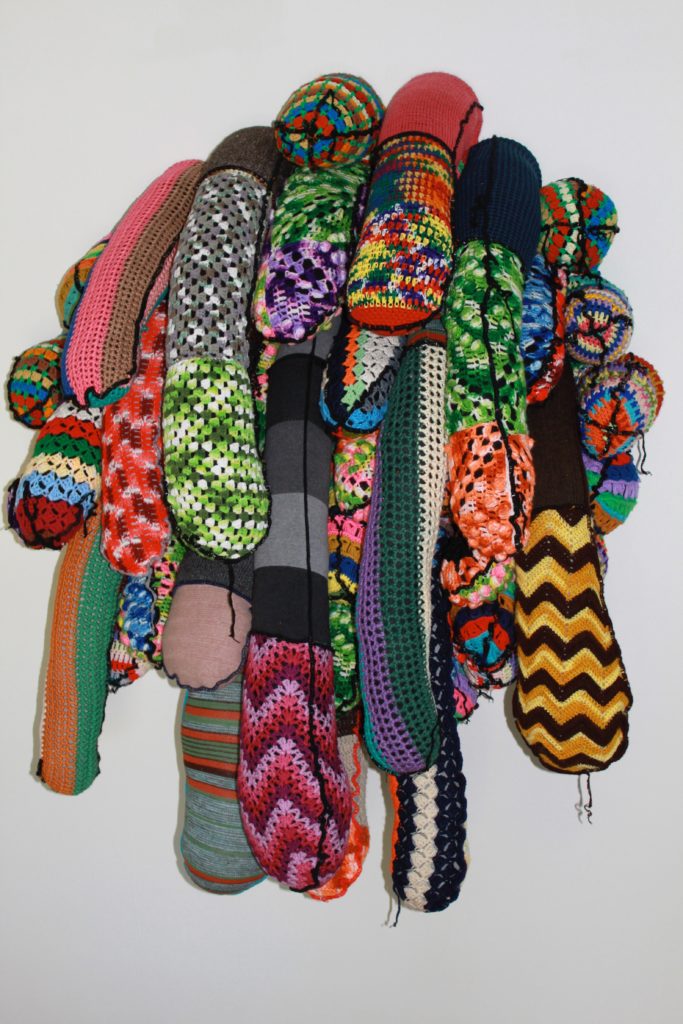

Rainbow of Tears, 2015, found afghans and polyfill, 216 x 79 x 14 inches.

CB: You use many different mediums and techniques to conceptualize your philosophies into form. “Rainbow of Tears”, features a towering tear-dripping sculpture composed of used multicolored afghans pieced together as one. The importance of rules: In what way does the method affect your research?

MB: I don’t like to bind myself to “rules” or “systems” since my overall project is to break down social hierarchies and question institutional definitions: to negate and transform rather than “modernize.” I go through periods of research and then put it all away and then re-discover the research later. This way I feel that the work is informed organically through the osmosis of memory. I like to try to re-energize clichés, as well, in a kind of redemptive resurrection: an act of spiritual Pop.

The sculptural waterfall is constructed using a childlike representation of water, or “tears.” Irony and sincerity co-exist in the naive representation of a natural phenomenon, forming giant clown tears. This kind of affected emotional response to the California drought is ironic, like posting a crying emoji, and harkens back to the 1971 Keep America Beautiful crying Indian–the ubiquitous television ad, with Iron Eyes Cody, “a Native American man devastated to see the destruction of the earth’s natural beauty caused by the thoughtless pollution and litter of a modern society.” The collection of used afghans, again, speaks to loss–a communal emotional loss.

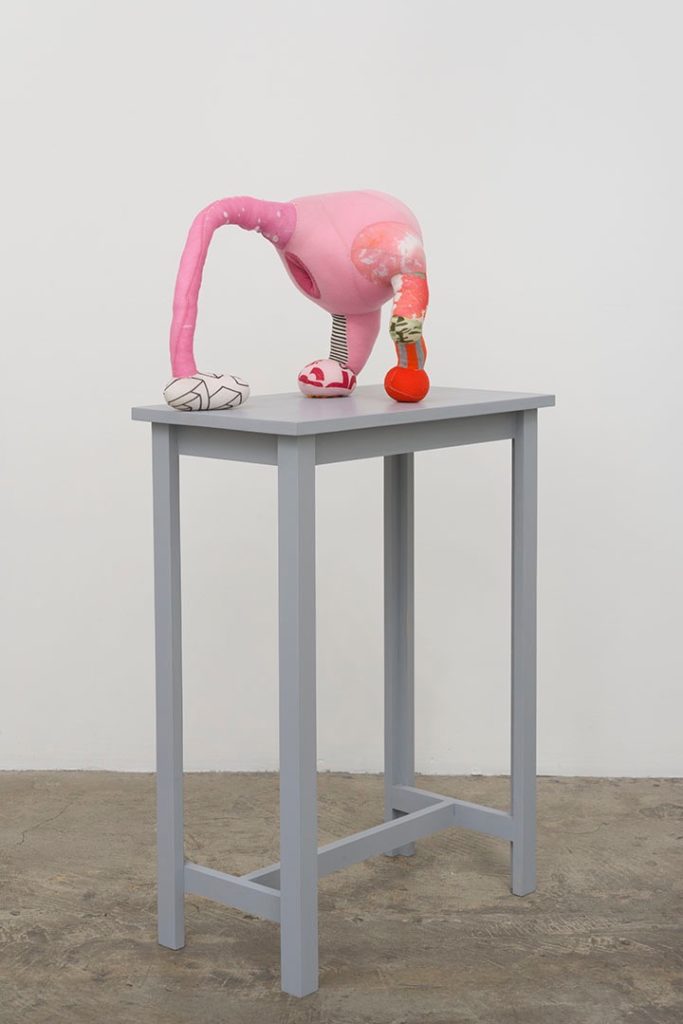

Model for the Monument to Postponement Obsolescence, from Monuments to the Failed Future, 2013, found t-shirts, polyfill, wood base, house paint, 45 x 24 x 13 inches.

CB: Can you introduce the “Monument to Postponement Obsolescence” and the “Monument to Accelerating Impermanence”, of 2013?

MB: In the series, Monuments to the Failed Future, I wanted to mimic the manifesto-style of the Constructivists, as well as make a direct reference to Tatlin’s model, The Monument to the Third International. The term “postponement obsolescence” refers to the continued manufacture of out-dated features or parts for economic reasons–cost concerns. I liked the way the term segues into climate denial and the continued use of known pollutants for corporate profits. The spherical shape of this proposed monument reflects modernism’s use of the sphere as a visionary form. Forms of pure geometry carry this idea of purity that Modernism exploited. Making it pink with three legs and a hole in it is a joke: to continue the use of outdated and dangerous ideologies even as the physical structure is hollow and collapses on itself.

Model for the Monument to Accelerating Impermanence, from Monuments to the Failed Future, 2013, found t-shirts, polyfill, wood base, house paint, 40 x 30 x 23 inches.

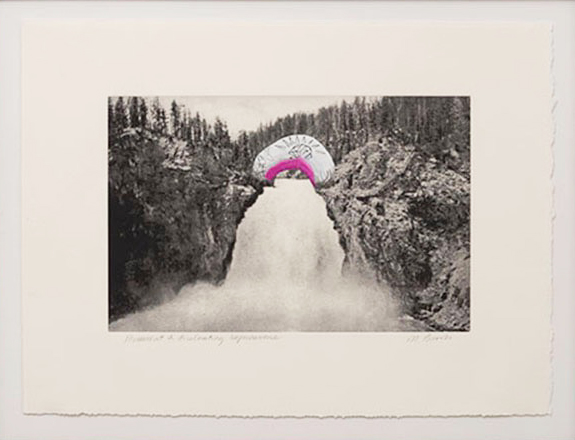

Monument to Accelerating Impermanence (Upper Falls of the Yellowstone), 2013, gouache on digital photogravure print, 9 x 13 ½ inches.

Each model for a monument in this series came with an in-situ image. All the models are painted on images of their ideal sites, which were all iconic American landscapes printed from vintage postcards. The postcards are enlarged and printed using a digital photogravure technique to look old-timey and refer to the historic narrative of American expansion, or Manifest Destiny, the manifesto that led to the genocide of Native Americans.

Monument to Accelerating Impermanence (Upper Falls of the Yellowstone) also points to the accelerating pace of ecological threats and dwindling water resources of the Western States. The postcard used for this print of the upper falls of the Yellowstone describes it as a “celebrated spectacle of nature in the highest state of its grandeur.” The vintage postcard image evokes a lost arcadia and heightens the sense of current and future loss of resources and moral authority. The found t-shirt fabric that was used to create the model for this monument (the sculpture above) is from a brand campaign. The logo-emblazoned t-shirt along with the nostalgic scene from one of our greatest National Parks, reflects our current political environment where business interests trump the reality of the limits of our natural resources.

CB: When do you think a work can be considered successful?

This is a philosophically difficult question! I think all art objects are cultural artifacts and speak to their context–the particular time and place where they were made. So the answer might be, a work of art is successful when the artist deems it finished.