by Camilla Boemio

This conversation with Matthew Smith is expanding his artistic sublime practice from photography to writing. He is a writer and a photographer based in North London, in Great Britain.

His poetry has been published in magazines and journals including The London Magazine, Acumen, Envoi, Poetry Salzburg Review and Orbis. He was a winner at The London Magazine Poetry Prize 2018; and he won the Orbis Readers’ Award in March 2019.

His first photo series Chora was exhibited at Hagi Art, Tokyo, January-February 2020, and Landabout, Tokyo for the following year. It was shown at Arte Spazio Tempo in Venice in April 2021.

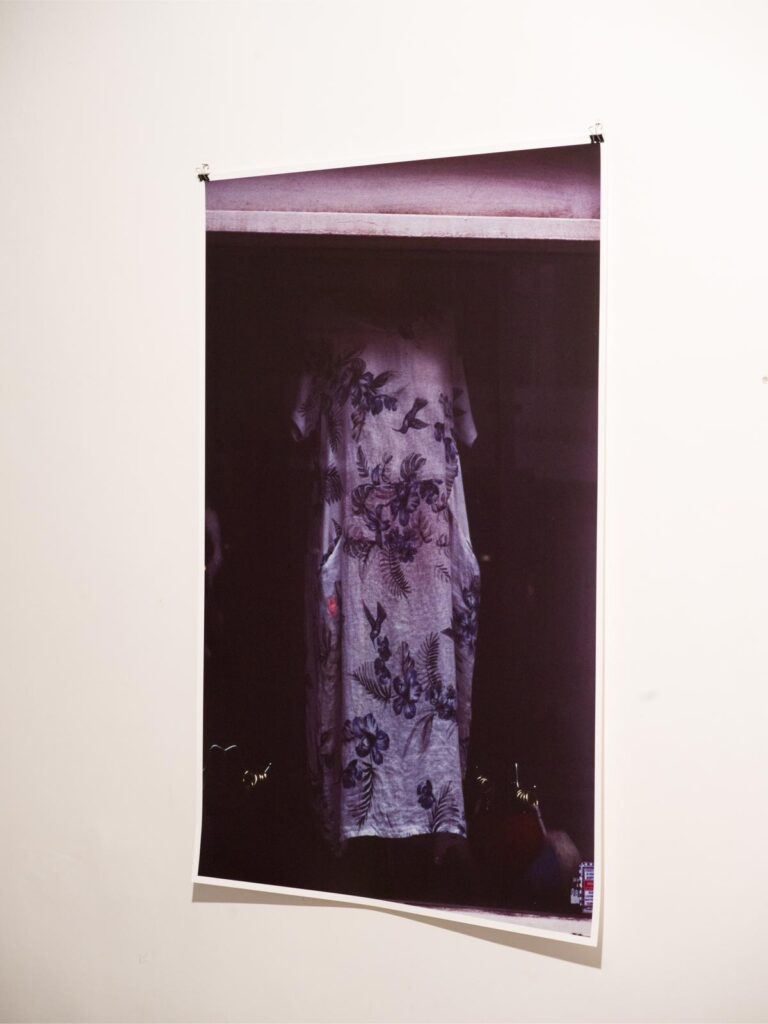

His new series Ascension won honourable mentions at the Lucie International Photo Awards 2020, the Moscow International Foto Awards in 2020 and 2021 and the Tokyo International Foto Awards 2022. Ascension has been published as a photobook by Red Turtle Photobook in Spring 2023. In April 2023, Galleria Bruno Lisi has presented Ascension with my curatorial role and the collaboration with AAC Platform team.

Camilla Boemio: What artists and writers were most influential in your beginnings? Where can the roots of your work be found?

Matthew Smith: In childhood I would read a lot, and the Greek myths and Tolkien were key for me. I was interested in highly imaginative storytelling, which means very visual storytelling, and I would draw a lot. I remember seeing a Studio Ghibli film, Laputa, on TV when I was a kid, maybe 30 years ago, and anime was new to us in the West at the time. I was captivated by it. Later, writers like Borges, Nabokov and Robert Frost inspired me. Andrei Tarkovsky is my favourite film director, and his work has had a big influence on my photography.

CB: How do your writing background and photography engage in a dialog?

MS: I’ve realised that my photographs always want to be part of a series, and that this series inevitably turns into a narrative of some kind, which feels novelistic. But in another way, making a collection of images is similar to making a collection of poems. You are less restricted than when you are writing a novel, as you are working with pieces of material, instead of one great block of work. You are free to move them around more easily.

CB: What was your first experiences with photography?

MS: I took a course in pinhole photography when I was a kid, and later I took my dad’s Olympus camera to Venice on a school trip, with some black and white film. I loved the way that you could work in the street, outside, anywhere you liked. You could explore the world and be creative at the same time. The private and the public world mix together. My school had a dark room where I could develop the rolls, and I was happy with the pictures. But for some reason I put photography aside and came back to it later in my life.

CB: How would you describe your photographic voice/language and way of working/creative process?

MS: I wouldn’t want to define my voice too strongly but I feel compelled to make work that comes from the way we engage with the world, the way our dreams and our imaginations seem to interact with the world around us. I’m always trying to take pictures of something inside myself and others. When I’m walking with a camera, I am in a harmonious frame of mind, a flow state. It’s pure pleasure.

CB: What is your greatest source of inspiration? Can you introduce your method?

MS: It’s just life in general. Some of my work seems like street photography, but my photos might be of anything. Walking around cities seems to be the best way to find an abundance of things to photograph, and nature is included in this, as it is changed in interesting ways by the city. So I would say that cities and the people who live there are currently my main source of inspiration.

CB: Which question or theme is central in your work?

MS: I try to make beautiful pictures that express something you can recognise, that is normally hidden in darkness.

CB: What do you need in order to create a photographic serie?

MS: For Ascension and Chora it was simply a camera and film. For Ascension I used a Hasselblad 503cw, a Leicaflex SL and a Leica M4. I am working with a digital camera at the moment, and I’m experimenting with flash this time.

After getting to know the artist better, I now introduce his new serie, which I curated for an exhibition in Rome.

From his writing “After a time, deep in this place I found scenes I seemed to recognise, memories I seemed to own. It was a city and something more, a garden perhaps, or another realm. No matter how far I walked, the paths and the byways never seemed to end. What was I looking for? I knew only that I was looking.”

CB: Can you introduce Ascension? What inspired you to shoot this series?

MS: Ascension began to take shape during a time of my life that was very challenging and uncertain. I was dealing with a lot of instability in my work and in my life. Then my first wife was diagnosed with a brain tumour and the doctors gave her one year to live. Our second daughter was born immediately after the diagnosis. Then lockdown began, which had a big impact on my business. So many challenges appeared in a short space of time. Gradually, I realised that Ascension was about a journey within. It’s about finding new creativity and new ways to move forward in the darkest of times and places.

CB: In your opinion in what way can landscape be considered physical, mental or psychological?

MS: It’s all of these. When they come together, that’s the terrain of myth, of storytelling.

CB: How does the human figure appear in your narrative?

MS: In glimpses, clues, moments, close up and farther away. Sometimes remembered, sometimes imagined. The world of Ascension sometimes seems to be empty of people, but it’s not.

CB: Should human beings still contemplate and understand landscape, the nature of its existence, through its representation?

MS: Yes, contrary to what many photographers say, there are always new ways to represent natural landscapes. Nature is inexhaustible as a subject, but the photographer must be willing to respond personally to make their own journey through the natural landscape, and always be strong enough to resist the inevitable temptation towards making clichéd images.

The photos of the exhibit in the photo-gallery below were taken at Galleria Bruno Lisi by Gabriele Mizzoni.

Camilla Boemio is an art writer and curator, who curated projects around from Los Angeles to Odessa, Ukraina. She is a member of AICA (International Association of Arts Critics). Her recent curatorial projects include: the talk Zoé Gruni: Corpo come frontiera at Pistoia musei (2023); her role to associate curator at Pera + Flora + Fauna. The Story of Indigenousness and Ownership of History,anofficialCollateral Event at 59th International Art Exhibition: La Biennale di Venezia (2022); Jérôme Chazeix The coat of hipness (materiali velati) in AltaRoma2020 agenda at Label201 (2020); Marina Moreno: Dance as sculpture in space supported by Arts Council England (2019-2020); The Contemplative Edge. Il Mondo Nuovo. a performative Parallel Event with artists Mathew Emmett and Greig Burgoyne at Museo dell’Arte Classica, in Roma (2022). In 2016, she was the curator of Diminished Capacity the first Nigerian Pavilion at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia; and in 2013 she was the co-associate curator of Portable Nation. Disappearance as work in Progress – Approaches to Ecological Romanticism, the Maldives Pavilion at 55th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia. In 2018, she took part in the VVM at Tate Liverpool.