In the last issue of the Mirror I described the 14 x 7 foot oil on canvas mural “Richmond, Industrial City,” that is currently undergoing restoration at the Fine Art Conservation Laboratory of Scott Haskins in Goleta California. The mural had been delivered to his workshop on May 23rd, and at the end of September, I decided to see the progress made for myself. On late Monday morning of September 28th, I arrived at Haskins’ studio and was warmly greeted by Haskins and his staff.

After a short and very interesting tour of the facility and the projects underway, including a 150 year old portrait of Alexander Hamilton that tangled with a big dog in the back of an SUV, I was led to the space in the rear of his shop where the large Victor Arnautoff mural was laid out on an even larger work table.

I had never seen the actual mural in the flesh, and I was pleased by both its artistic qualities and its overall good condition. Head conservator Virginia Panizzon gave me a review of the principal technical features of the conservation work already done and the work still to be accomplished.

The mural lies very flat and most of the rippling that the mural exhibited from being tightly rolled for such a long time, has been successfully eliminated by the removal of the thick layer of lead white adhesive and plaster clinging to its backside and by relaxing the canvas on the shop’s heated vacuum table.

The heavy layer was softened in a gel medium and then delicately scraped away, square inch by square inch The technical term is levigation, by which a non-water soluble material can be removed when wet.

The remaining adhesive is very hard and thin and has been leveled to an even thickness to avoid lumps or ridges showing through the canvas when attached to the rigid fabric support. The residual lead will be “encapsulated” to meet legal EPA standards of safety for potential exposure.

Virginia showed me the warp and weft of the original canvas now exposed and I could feel the true thickness of the heavy canvas supporting the pigment surface. I want to emphasize that great weight has been taken away from the entire painting, contributing to its long term stability when hung on a wall.

The next step is to complete the removal of the old yellowed varnish. Several test patches swabbed clean reveal the bright colors of the original paint. Then every inch of the mural will be inspected for secure paint adhesion and for flaws and nicks that will be touched up with matching colors. Scott Haskins considers that the existing damage mostly occurred when the canvas was flexed in pulling it off the post office wall. With touch-ups completed the mural will receive several applications of archival varnish.

When all is ready, the restored mural will be attached to its stiff white Monotech 370 support with a reversible archival adhesive. Monotech is an architectural woven polyester fabric that is both stiff and flexible, and the piece intended to back the canvas mural is cut larger than the size of the painting in all dimensions. Grommets will be punched through this border so that the completed assembly can be mounted to a vertical surface with suitable hardware.

Scott and Virginia agree that the mural will be finished and ready for delivery in October, 2020

A correspondence among equals.

One of the most valuable resources in the museum archives are copies of the complete correspondence between Victor Arnautoff and his employers in Washington. The contract price was $1,100, made in three payments, the last on the satisfactory installation of the work in the post office. The sum was equal to $20,450 in 2020 dollars.

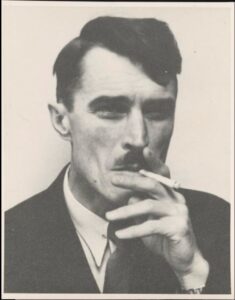

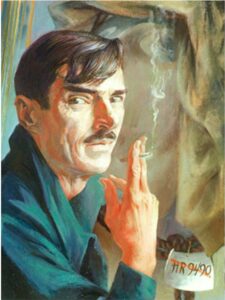

Arnautoff knew his government employer, Edward Beatty Rowan, Assistant Chief of the Public Works of Art Project of the Federal Works Agency, because they had worked together before. Rowan (1898-1946) was a skilled artist himself, having been a student and member of the mid-West art colony around Grant Wood. (We all remember Wood’s iconic American Gothic.) His experience with Wood influenced him to be a strong proponent of Regionalism, depicting the lives of ordinary Americans in understandable images. That was the sensibility that informed the commissions he sought for his public buildings.

He was also an art historian and teacher, and he was a skillful manager of the large number of artists that were recruited to decorate government buildings in the late 1930s.

The correspondence began between the men began on April 22, 1940, and because of the war in Europe, there was some difficulty in securing the highest grade linen canvas, but a large enough span was purchased from a dealer in New York.

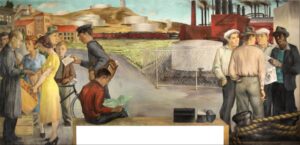

By August 6th, Rowan had accepted the colored cartoon of the design and urged the paymaster to release the second instalment to Arnautoff. He is not without reservation about the composition and suggests that Arnautoff change the grouping of Richmond citizens on the left side, finding the image of a mother with children, back to the viewer, “uninspiring.”

Rowan wrote, “The boy reading the paper immediately above the door should be the prototype in the direction of which you should work. He is beautifully and sensitively achieved and the workmen have a certain interest… but for us in this office the group on the left is quite without inspiration….I frankly hoped from the preliminary sketch that this work was going to be more exciting and alive throughout than the cartoon reveals.”

In suggesting changes in the submitted sketch, Rowan exhorted “I expect unusually fine work always from you.” The assistant chief could only make such entreaties of his stable of artists because they trusted his taste and judgment. A mural like this could enter the realm of fine art but could also descend to the blandest of illustrations., and his job was to ensure finished works that excited all involved. Rowan understood that the “decorations” had to remain relevant to many viewers for a long time to come.

A mural mystery resolved

In my previous musings, I noted the mid-1940 origin of the composition prevented the black worker on the far right side from having had employment in the Kaiser shipyards, to arise many months in the future.

Arnatoff noted that when he was casting around for a subject for the painting he spoke to the postmaster, he spoke to the editor of the Richmond paper, he spoke to city officials and to the man and woman in the street.

He wrote to Rowan in June, 1940, with the germ of his idea, “After several visits to Richmond and discussions I came to the conclusion that one general subject would be best. Richmond is an industrial city. The main industries are Standard Oil Co. oil refineries, Ford Assembly plant, Color-pigments Factory, Cannery, Pottery and Tiles; it is also a port.

“The population in Richmond consists of workers employed in the industries and merchants.

“We decided that the main subject of the mural should be the people of Richmond ; oil tanks and factories as a background. Therefore in my sketch on one side I presented collective bargaining ; on the other side people walking on the street, going about their business.”

While he didn’t mention the Pullman sleeping car company which was a major employer of Black men in the 1930s, with their western terminus in Richmond, he did mention the Ford Assembly plant, which hired blacks and Standard Oil Co., which did not.

He then mentioned collective bargaining and some rusty cogs began to rotate in my brain. In May of 1934, Victor Arnautoff was the lead painter completing the fresco murals in Coit Tower, at the very moment the epic longshoreman strike broke out up and down the West Coast. In the decades before air transport and the giant network of highways, most goods were carried in ships that were laboriously loaded and unloaded by hand.

The great demand of the strike was to end the blue book system of hiring dock workers, based on favoritism and bribes, and to replace it with organized collective bargaining with clear new rules about how labor was hired and paid. While humping cargo was a hard and dangerous job, it was choice work if you could get it. Blacks were only allowed to work on two piers, but organizer Harry Bridges recognized that black-white solidarity was the key to success in San Francisco’s general strike.

Bridges went to black churches on both sides of San Francisco Bay and asked the ministers if he could say a few words during the Sunday services. He begged the congregation to join the strikers on the picket line, and promised that when the strike ended, blacks would work on every dock on the West Coast.

The waterfront strike ended on July 31 when the International Longshoremen’s Association was recognized by the shipping companies. Bridges kept his word: all piers were opened to blacks. They began to get the same work as everyone else, and some later became union officers. Bridges was quoted as famously stating “that if only two longshore workers are left on the docks, one would be black and the other white.”

The result of the strike tremendously impressed Arnautoff, who had featured African-American in several of his paintings, most notoriously as slaves owned by General Washington in the Washington school frescos completed in 1936. He had equated blacks in America with serfs in his native Russia and with landless peons he observed when he worked in Mexico with Diego Rivera.

So now the grouping of four workers next to the mooring bollard and ropes of the docks made sense. They were all longshoremen whose lives had been ennobled by the power of collective bargaining. The black man looks out to the viewers with dignity and purpose, and a sense of belonging.

While some protesters died and more were injured and arrested, Arnautoff and his fellow painters has seen how men working together could overcome seemingly immovable forces, and he celebrated the victory of collective bargaining in his mural for Richmond, Industrial City, soon to be beautifully restored as one of the city’s crowning artistic glories.

Marvin Colllins is a San Francisco Bay Area professional photographer and researcher.