I couldn’t sleep that night, still in shock to hear that Ammar had called Jamil just before he died, and that my bastard brother had never mentioned it. Why would he do that? I also couldn’t wait for morning to come so that I could see Nouman. He was the only one now who had all the clues. I shared a room with Um Suleiman, who fell asleep instantly, the moment she lay down on the foam mattress on the floor, covering herself with a duvet and a very thick blanket. She was snoring like a train, perhaps dreaming of that very same train she used to ride.

My main concern in the morning was how to leave Jabalia Camp without being spotted by any of my brothers or their families. Abu Suleiman wanted to walk down from Tel El Zaatar to El Trans Road in Jabalia Camp to catch a cab to Gaza City, but I insisted on him going and bringing a cab to the door, so I could sink into the back seat without being spotted. He did just that, with an added treat of a fresh falafel sandwich and a cup of sweet mint tea, which he handed to me as soon as I got in the car and waved goodbye to Um Suleiman.

Her husband sat in the front passenger seat, said his assalam aleikom to the driver and fell silent, unlike many men in Gaza who seem to strike up a conversation with a stranger in the blink of an eye. The driver didn’t look very impressed by his unsociable passengers, but he kept his eyes on the road and sped ahead. I put my head down and wanted to cry – I was so afraid. I didn’t know what was going to happen from now on. I had let the genie out of the bottle and had no control over it anymore. I couldn’t even make my three wishes. What else was in store for me? I started remembering the number of times Jamil had told me off for trying to find a detective. I felt his voice ringing in my ears, telling me it was a stupid idea: that I was wasting time trying to find who killed my husband; that it would all lead to trouble; that I was crazy and needed a mental hospital instead. Maybe he was right. Maybe I should have left things as they were; it wasn’t as if Ammar would have come back from the dead anyway.

But I was not only afraid of what had happened or what I was going to discover. I was also scared of the man whose murderer I was trying to find – yes, my very own husband. He had suddenly become a stranger, a new person with another phone, a different circle of friends, conversations that I was not part of. They could have been talking about any other random person, but not my Ammar. I remembered once walking with him down this very same road, on El Trans Street, going down the centre of the Camp. There used to be a café, just by the taxi station near El Markaz Police Station. It was mostly men smoking shisha there, but we went in a few times and smoked too.

It was a lovely evening. It was very warm in late July, but a cool western breeze from the Mediterranean made it pleasant, despite the noise of beeping cars, braying donkeys, and the cooking gas seller who kept banging on a gas canister with pliers and had some weird music playing like an ice cream van. The place was filled with the smell of apple flavoured tobacco burning in shishas everywhere. At 9 p.m. on such a beautiful evening, the Camp was brimming with life. Kids were walking shoulder to shoulder – discussing politics, of course – and then the call for prayer made everyone pause whatever they were doing, as if a remote control was pressed before the hustle and bustle returned.

On that very evening in 2004, when Ammar and I were still engaged, he told me that we should always be open with each other and tell the truth no matter what. He said that if I ever discovered he was lying to me about anything, no matter how big or small, I should walk away and not look back. I thought he was being overly dramatic and teased him about it, but he was not impressed. He looked dead serious. He was staring at me hard, so I blew him a kiss and smiled.

That night we made love passionately in the new flat we’d bought together and which, funded mostly by his rich parents, we were still doing up. There wasn’t any furniture yet. We got a couple of take away shawarma sandwiches and two Diet Cokes from Abu El Abed in El Saha and took a taxi to the flat on Talatini Street.

We weren’t meant to be alone in the flat, despite the fact we were engaged.

‘People will talk,’ I said to him, as he stared at me, undressing me. I felt his warm hands on my shoulders as he unfastened my bra, then gently touched my breasts. He was indeed a gentleman, he never rushed a thing. He caressed my body for a long time before he too undressed, and we made love passionately on the floor. We lay on our backs in the empty flat and looked at the ceiling, smoking cigarettes and dreaming of a future that looked so bright ahead of us.

***

Now, that evening felt different, as if it had been a setup, a big trick, a trap which I fell into. Did he really mean what he said? Did he know that one day I would discover his lies? But why? And what were they? The man I shared a bed with for a long time was not the man I knew; he was a different person, and it frightened me.

Suddenly, I remembered Zakaria Abu Qamar, who was being interviewed by Nouman the other day. I realised I hadn’t had the chance to think about it and why he was there in the first place. Before going to see Nouman, I wanted to get more details, I wanted to understand more, to feel in control again and not leave the whole thing in his hands.

The car came to a stop for a moment near Khadamat Jabalia Sports Club, where Zakaria’s house was, behind a little corner shop where he used to hang out in the evenings sometimes. Without thinking, I opened the door of the car, jumped out and started running. Abu Suleiman was shouting at me to come back, but I didn’t slow down or even glance behind at him. I turned right into a small unpaved alley, splashing through a big puddle of water coming from a leaky pipe outside one of the houses.

It was too early to knock on Zakaria’s door, so I kept going, from one alley to the next, going around in circles and trying my best to avoid being spotted by my brothers, their wives or children. I kept walking, heading down one alley after the other, cursing the way this Camp was built. They all looked the same, dozens of houses with grey unpainted cement bricks. The whole place was like a maze. Most of the houses didn’t have roofs, but just a few asbestos sheets that covered the temporarily erected walls, placed on top of steel poles. The sheets were littered with stones to stop them from flying away in the cold winter. Those houses were useless, I thought – boiling hot in summer and freezing cold in winter; a tiny upgrade from a tent.

As it got to 8 a.m. and I got tired of walking, I decided to head back to the Sports Club and find Zakaria. I didn’t know what I would say to him or why I was going to see him in the first place. But just as I got back to the main El Juron Road, very close to Zakaria’s house, I saw her. My mother was standing there looking straight at me, as if she had been there all the time, waiting for her little daughter to come back. My heart dropped; I had been a bad daughter and hardly asked after her.

***

The thing with my mother was that she was one of the kindest people ever, and most likely the calmest human being you could ever meet. Despite all the destruction around her, she had a calming effect on other people, a gift which that demanded respect and authority.

But for that very same reason she could sometimes appear passive, not quite there, not engaged in things that made me angry or passionate. As a teenager, mourning the death of my father, who was the complete opposite to my mother, I learned not to share my emotions with her because she never engaged with them. She never understood what it meant for a teenage girl to lose her father, to lose her first love for a man. To her, it was a matter of practicality: how to make the funeral arrangements; how to keep Issa and Jamil emotionally strong; what they needed to do over the three days of mourning; who was going to get the bitter black Arabic coffee; who was going to light the fire, rent the marquee and plastic chairs; buy the dates and cigarettes to hand out to people; which Imam was going to read the Quran.

I thought it was her way of coping, that after the funeral was over and everyone had left, leaving her to her pain and agony, she would come to me – she would hug her only daughter and maybe cry. And she did, after she stopped being mechanical about it, sorting out father’s debts and collecting money that people owed him. She came to my room ten days after the funeral; I was lying on my bed staring at the ceiling. She sat beside me, started stroking my arm, and I smiled at her. Then, she hugged me tightly and cried for a long time; she sobbed like a baby, letting go of all those emotional masks she had previously worn. I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t cry as that would have made her worse, so I started singing to her – a song that Dad always sang, and whenever he did we knew he was in a good mood, that we were getting a treat that day.

Wa Hada El Bulbul El Roman

Smieto Bil Leil Yeghani

The nightingale landed on the pomegranate tree

I heard him at night singing

It woke up my little one who was happily asleep.

The nightingale was visiting the groom next door

He said to him: think no more, your bride is the best in town.

Mother joined me in singing; the words sounding nasal as the tears jammed up her voice, remembering a time when father came home and he was so happy. He was singing at the top of his voice, we didn’t know what was happening. He was just happy. So we all started singing, Jamil and Issa clapping hard while providing the male chorus to the song, and I ululated. Some of the neighbours knocked on our door to find out what was happening so they could celebrate with us. But there was no news or party, it was just a happy moment, stolen from amongst the struggle around us. That night, Dad went out and bought lots of freshly made kebabs from El Shaeb Restaurant in Jabalia Camp central market. He also sent Issa to get us the mouthwatering sweet kunafa for dessert.

Dad was very generous in lending people money whenever they needed it. He was a contractor in Tel Aviv, taking a lot of Palestinian workers into Israel to do construction jobs, cleaning and farming in the days Israel allowed us to work in our stolen land for money. I asked father about this many times. When I was nine years old, I wanted him to explain why he worked for the people who colonised our lands and made us refugees in the first place.

‘For two reasons, my clever daughter: one, because we are not allowed to build factories and make our own economy succeed here. We can’t have heavy industry or import stuff without Israeli permission. The second reason, which is far more important, this land is ours and we want to look after it, whether it is governed by us or by people who come from Russia. The land is the same; she doesn’t change. She knows us and we know her – she is our mother.’

I thought of his wise words. At the time they felt magical and romantic. The way he referred to the land as ‘she’ was innocent in a way, almost sentimental.

Now, all of that was gone, as no Palestinian workers were allowed into Israel anymore. They were replaced by new Thai, Vietnamese and Filipino workers instead.

After my father’s death, my mother became the boss temporarily, until Issa was old enough and strong enough to become our second father. She handed over managing the family affairs to him and became very passive in the family – well, certainly with me. I often wondered what would have happened if we had got on a little better, if we had become friends.

My parents got married slightly later than was the habit in Gaza in the 1970s. Dad was still in his early career as a builder in Israel. Zuheir El Tanani was a handsome man who spent his whole week away in that ugly new city called Tel Aviv, while mother taught maths in a local UN school. She had studied at Cairo University, which was unprecedented for a young woman from the Gaza Strip, but her adopted father let her follow her dream. Despite her four brothers’ protests, he paid for her education and made sure she had comfortable accommodation in his cousin’s four-bedroom, 1930s flat in El Zamalek, a posh neighbourhood in Cairo.

They met when my father came into the house of Mohammed Abu Daiah, mother’s father, to give a quote for building a second storey. Mother often said that she fell in love with Father the moment he walked into the house. They were engaged quickly, and in 1974 Issa was born, seven years before me and three years before Jamil.

***

That morning, on the second day of 2017, my mother was standing there on the corner of the nameless alley where Zakaria lived. She was waiting for me, hands crossed, staring with unfocussed eyes. Nouman’s and Abu Suleiman’s instructions were not to let anyone know my whereabouts. I slowed down to see her expression better, but as usual, she didn’t display any emotion – she was such a hard woman to read. I hurried towards her and we embraced. She felt very warm in the morning chill. She towered above me, stroking my hair, while hugging me tightly. It was exactly what I needed. I had to cry, I had to let out all my stress.

‘Mother, what do you know about how Ammar was murdered?’

The question seemed to startle her, and she pulled away from me.

‘As much as you do,’ she replied after a moment’s thought.

‘Do you know what I know, what I’ve learned over the last couple of days?’

She shook her head and stared at me, encouraging me to continue. But something told me to stop and not tell her I knew Jamil had spoken to Ammar hours before he was killed, that my husband and brother had a strange relationship which I could not understand, that there were some dealings between them. I looked at her eyes for a long time, trying hard to decide whether to tell her or not, but I couldn’t. I had to trust Nouman – I could not spoil it, not then, not now.

‘How come you are here, Mother?’

‘I could ask you the same question; you live in Gaza City and you came all this way, at this hour, without telling us. What are you doing here?’

Her question startled me. I didn’t have an answer, a credible reason to give her for why I was in Jabalia Camp at 8 a.m.

‘I came to see Nouman. He is at El Markez today and asked me to come over. So I came a bit early.’ I had to think on my feet but I knew that mother wasn’t convinced. She just nodded.

‘Let’s have breakfast,’ she said, and started walking without hesitation or waiting for an answer.

We walked back to the main El Juron Road, past the Sports Club and all the way down to the police station in El Markez, past the UN Centre for Refugees. A lot of people were queuing already, with their blue UN cards that allowed them some rations. Sacks of flour were being loaded on donkey carts, ridden by kids no older than eleven years old. Others were leaving the queue loaded with gallons of vegetable oil, dried milk and cans of corned beef. Everyone in Jabalia Refugee Camp had a blue UN card that allowed them some basic supplies – our supposed compensation for losing our homes and land in 1948.

We walked down to El Merkaz Square, turned left and started climbing the hill towards El Fakhoura Girls School. Abu Ismail’s Humous & Falafel Restaurant was very tiny and modest; only a couple of plastic chairs and a small table stood in what looked more like a corridor than a restaurant. He wiped them down for us and immediately brought a couple of cups of mint tea without us having to order. The smell of mint was very comforting, I held the small cup in both hands to warm them and let the scent penetrate my nose.

‘Listen to me, daughter,’ she said sharply, as she put down her cup of tea, ‘I have never stopped you doing what you wanted, but this is getting out of hand.’

‘What is?’ I stared back at her. ‘Do you know something I don’t?’

‘I don’t know anything, but I can guess. I can see through things more than you think I can. Strange things have begun to happen since Nouman started interfering. I have no doubt that his intentions are good, but I don’t trust anyone anymore.’

‘Mum, why are you saying this? Why can’t you understand me? You have never tried to understand how I feel.’

‘I do,’ she responded sharply, ‘I do, but you refuse to see it.’

‘Are you trying to protect someone?’

‘Someone? Who? I am disappointed in you, Zahra.’

Abu Ismail brought some hot falafel and a bowl of foul beans for us with freshly baked bread, chilli sauce and olive oil. Without even asking us, he poured the chilli sauce on the humous. It made me smile when I saw customers saying they didn’t want chilli on their food – the faces of the café staff were always a picture, as though they couldn’t believe what they’d just heard. When I was at school, Mother always made us chilli sandwiches for lunch. Sometimes she added a dash of olive oil and lemon if she was feeling generous.

Abu Ismail placed everything on the table without saying a word, as if he understood how tense the conversation was. He also brought two cans of 7-Up for some reason – another eating habit in Gaza which I never embraced.

‘I need to find out who killed my husband, Mum. I made this clear to everyone ages ago; I am not going to stop now. I am sorry, I know this is not important to you, but it is to me. I will not stop, not now.’

‘Even if it leads to worse things?’

‘Like what? That’s what I don’t understand. You keep saying these things without explaining. Why won’t you tell me, why won’t you speak to me like all mothers speak to their daughters?’

I was shouting by now. Luckily, Abu Ismail had a queue of workers who were half-asleep, waiting for their falafel sandwiches. He was too busy taking orders to pay attention to us, but a few of his customers stared at me as I raised my voice.

‘I don’t have anything to explain; I just have a feeling. It’s the years I’ve lived in this Strip that make me realise this is leading to trouble. Stop it right now, I am telling you to do so. I am begging you from a mother to a daughter to just put it behind you and start your life again.’

‘I am sorry, this is not up for discussion and no one can tell me what to do.’

The silence which followed was painful. Her words and mine hovered above us. We could both see the effect of what we’d said to each other and that, from then on, our relationship was going to be different. She was not the disinterested mother anymore, she was trying to stop me from doing the one thing I wanted to do right now – finding out who killed my husband. I took out ten shekels from my purse and placed the coin on the table. She pushed it back towards me. ‘I am still your mother, put your money away.’ The coin fell off the table and rang loudly on the floor. A kid from the queue ran and picked it up and helpfully handed it back to me.

‘Let’s start again, my daughter. We lost so much in this damn war – let’s not lose each other. We are still here, we are family.’

‘Well, then let me do what I want to do. Please, Mother.’ She fell silent, swallowing back her tears.

‘Someone has come asking for your hand in marriage – a customer at Jamil’s blacksmith workshop. Jamil has convinced Issa to accept. They will be coming tomorrow to read the Fatiha Verse announcing the acceptance.’

‘You must be kidding me,’ I shouted as I got up. ‘Goodbye, Mother, tell them to fuck off. I don’t want a husband and certainly not one that Jamil has pimped for me.’

She was silent for a while, staring at me as if I had just confirmed to her what a total waste I had been as a daughter. I couldn’t usually read her thoughts but the look on her face said it all – she was disgusted.

I sat back down. ‘I am sorry for the rude choice of words, but Mum, listen to me, you and Dad married because you loved each other. You didn’t go the traditional way, why should I?’

‘But you married Ammar out of love, your way, and look what happened?’

‘Yes . . . I didn’t tell him to get killed, though. I am sorry, Mum. Try to understand me a little. I am not intending to get married at the moment and I know this will upset Jamil, but he’s got a few things to answer first.’

‘What does that mean?’ Mother asked sharply.

‘Mum, there are things you don’t know. For instance, has he ever mentioned to you that he spoke to Ammar only an hour and a half before he was killed? Why do you think that was? And why did he never think of mentioning it to anyone, particularly to me?’

She was silent again, staring past me as though I wasn’t there.

‘There must be a mistake, that can’t be true. Why would he do that?’

‘Well, that’s what I am trying to tell myself, but Mum we found a phone, another handset and SIM card which Ammar apparently used on many occasions. The last call that was made on that line was to Jamil and they spoke for approximately fifteen minutes.’

I could almost see a tear falling down Mum’s cheek, but she held herself together, took a deep breath and looked away, staring at the little falafels being thrown into the hot oil.

‘See, my daughter, this is not going to end well at all. Things will only get worse. Is Nouman now suspecting your brother?’

‘I don’t know, Mother. To him, everyone is a suspect, including myself. There’s also Sameeh who claims that he and Ammar stopped being friends, but I know they didn’t because I saw them together. I also saw Zakaria being interviewed.’

‘Zakaria, what, that idiot who’s a complete waste of space?’ Mum said, with a big smile on her face.

‘Yes, Mum. In fact, I am here to see him. I wanted to ask him what he talked to Nouman about before going to see the detective.’

‘What, are you a detective now too? See, my daughter, you are going insane!’

‘I am not, Mum, trust me. But my whole world has collapsed around me. The man I knew, or thought I knew, is not the same man who was killed. Ammar had so many dark secrets and I want to know what was going on. I think I used to be a fool, but not anymore. I want to know everything, even if it costs me my life.’

She stood up, preparing to leave, and left the coins for the bill on the table. She was smiling at me. She didn’t complain any further; she just nodded as if giving me the go ahead to carry on.

‘Be careful,’ she said, before she shot off. I wanted to stop her. I still had so many questions for her. How did she find me in the Camp that morning? Was it a complete coincidence?

Suddenly, I felt sad she had gone; I felt as though I wasn’t going to see her for a long time. I felt like running after her, I loved her so much and wanted her to stay with me all day. But instead I turned back and went to see Zakaria.

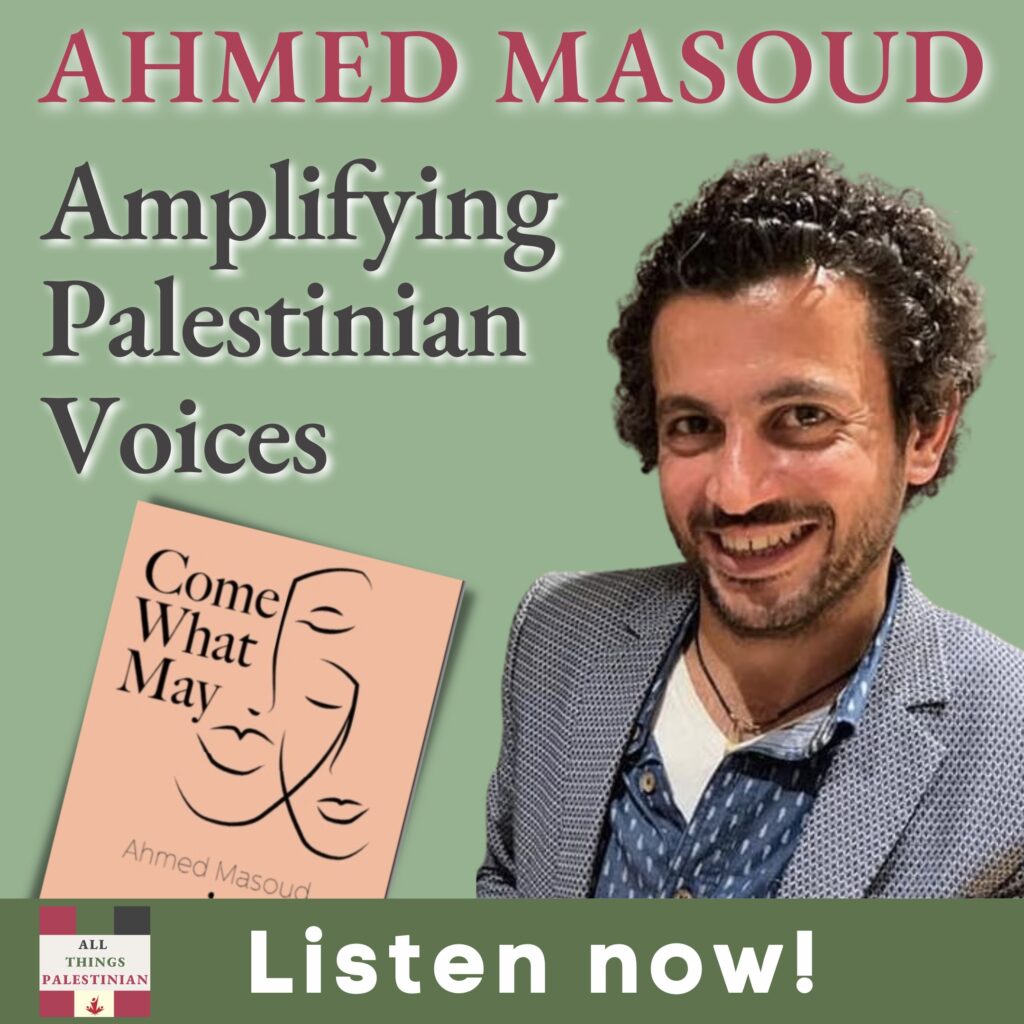

Ahmed Masoud is an award winning writer and theater director who grew up in Gaza and moved to the UK in 2002. His theatre credits include The Shroud Maker, (London 2015) which recently had a run in Chicago, and is the recipient of numerous awards . His debut novel is Vanished – The Mysterious Disappearance of Mustafa Ouda (2016), which is also been translated into Spanish and Italian. His second novel Come what May (Victorina Press 2022) has received favorable reviews; the Italian translation was published by Edizioni Valeria de Felice. Ahmed is the founder of Al Zaytouna Dance Theatre (2005) where he wrote and directed several productions in London, with subsequent European Tours. After finishing his PhD research, Ahmed published many journals and articles including a chapter in Britain and the Muslim World: A historical Perspective (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011)