Translated by Pina Piccolo, from the Italian review appearing in Carmilla online on April 4, 2023. Cover art by Giovanni Berton.

How do you recognize a poet? I discovered Antonio Merola during a reading: he was maybe twenty years old. For the first time, I came across a guy who promoted and supported the idea of the need for literature as life. And you could read this proselytizing in his eyes, in his posture, in his voice. His intellectual training was American, he fed on the myth of the Beats, the poets apparently rambling about life and wandering the avenues in the shadow of mushrooming skyscrapers. Even though he wandered around Rome and his anthropic points were explicitly Roman, his compass pointed to the west. One issue that struck me immediately was the importance he assigned to time. A time which, for biographical reasons, he claimed had been taken from him. Taken away. His time was in fact a time of life, a physical space where he could be, as well as write, poetry: where poetry and life fit together.

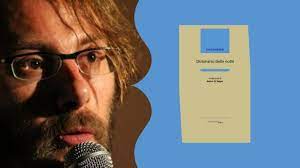

Almost ten years have passed since he had me read the first drafts of this work, which we had the opportunity to discuss together. Given these premises about time, few people are able to wait…. Being able to wait for the right time, the right publisher; more time wasted, you might think. But Merola has always felt a particular responsibility towards these poems, because they do not only concern his personal history, as those who read the collection in the coming months will understand: we are dealing with a poet who is willing to extend himself to others and who writes in the language of empathy. His collection Then I turned on the light followed the path of a time-consuming shape-shifting debut, which accompanied the author in his years of maturation as a poet and which necessarily changed with him, without, however, the author and the text ever betraying one other. And the collection has finally found its own poetic home: the Taut Editori project curated by Alberto Pellegatta, the very publisher responsible for publishing the groundbreaking anthology Planetaria – 27 poets of the world born after 1985 (2020).

Merola’s way of writing poetry is very specific, starting with his modus operandi which, as he kept repeating to me as the collection took shape over the years, starts from a special intuition of Allen Ginsberg: not understanding a text as you write it, but maybe understanding it later. This was perhaps the reason why the gestation of Then I turned on the light lasted the entire length of his twenty years of life: Merola tried to understand what he had written. He knew what he had asked of the poem, but how could he read the answers? Sometimes we tried to decipher it together. So far does not mean that at the level of metric construction Merola strictly follows the lesson of the Beats. Rather, it is a series of biographical experiences so cumbersome to the point that there was a mutual call between Merola’s sensibility and poetic writing. A vocation with no deterrents. It is a way of making poetry as if it were a constant oblivion: it spills out the moment it appears. So, in Merola’s poetics, the telling of life – which is, on the ontological level , a sequence of misunderstood events in the present – becomes magic, setting in motion dynamics that are found in very few poets. His lines belie a form of literary imagism. It is a sensibility that, like a child, enables him to read reality through a magical lens, turning him into a magician of words and dreamy settings, the creator of spells. Now it is clear that all this, starting from the question of imagism, leads Merola to stick out in the Italian literary panorama as a sort of peculiarity, outside the usual clichés. There are no other poets like him in Italy: his poetics remains the only case of this path. Below, I will try to provide some coordinates for understand the constellation of the poems making up this collection.

With the first section, Merola ushers readers into what was once for him The Old House. One of the ghosts, if not the main one, of his poems still lives within those walls: that is, an autobiographical wound that seeks to carry out “the repudiation of biography”. This first section, which for ancient reasons of my own I call the first act, in fact wanders around the memory of the child poet in the Prati district of Rome, among the avenues lined with plane trees, a neighborhood which today is part of the upper-middle-class city center, and the heart of the inner geography of the collection. Prati becomes the dramatic stage for a sort ofpoverty characterized by oxymoron, because the poet experiences it as someone poor among the wealthy, who needs to worry about daily survival, the choice between paying an electricity or a gas bill, putting daily meals together, “we were so little hungry / that we were looking for food in the garbage”. And if poverty is the protagonist of the first section of the book, its drama is subjected to a sort of magic spell.

With the second act titled Then I turned on the light, which gives the collection its title, Merola plays with the mirage of illuminating his biographical house, perhaps by managing to pay the overdue bill, by turning on the night light that protects the children from monsters and finally, I would say most of all, by turning on the love for the other – another, however, wounded by illness. But which disease? What kind? Thus, the section, together with the subsequent The search for a cure, is an empathetic chronicle that embraces without any prejudice those who in Italy, were it not for the for the reforms spearheaded by psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, would still be called the mentally ill. In part, this seems to follow the footsteps of that unique relationship between the American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre, which Merola had already explored in a previous book-length essay, proposing a form of “empathic criticism” (F. Scott Fitzgerald and Italy , 2018). Empathy is the key word to understand all of Merola’s poetics, because it is with that gaze that he reads the world: “but I’m afraid… I’m afraid of the life that I don’t write down”. And the life that we are not able to write down is the life that we have never tried to understand. This love between the poet and the you of these sections, is a weapon of defense from the monster that inhabits the mind, the woodworm, and only a feeble night light can protect against it, which is enough to wait for dawn, but too little to get out from under the bed: “I tried to take you far away,/ but the monster followed us everywhere”.

“I knew a man who collected cages/ to support men’s will not to know/ how to fly”, that’s how Act III, named The Companion of a Generation, begins. The poet’s chronicle expands to include a new wounded travel companion, anyone with scars of the mind, anyone forced to live in a blind labyrinth, prey to their own talking obsessions. It is implied that Merola is telling something he has witnessed, but that he is also protecting within the anonymity of the poetry. If we exclude the first section, of the biographical poet, all we have left in the entire collection are his eyes. A life of mirrors and echoes, of reverberations of the self “and yet I / am the same as you but I am / Antonio. This poem will also be called Antonio: Antonio: Antonio…”. The poet issues calls to himself, questions himself, searches for something but finds himself in front of the generational mirror. But at the same time, even in this section, the search for a possible cure continues, a cure that can cure everyone, as though the book were one uninterrupted, single great song. The book points out the absolute need for excess empathy. And the solution seems to be poetry itself, interrogated both as a “commodity that can be replicated”, that is, as a medium to provide the poet with a professional meaning for his being in the world. Once again, this is accomplished through the equation of literature with life, because this is a poetry of listening, which lends itself to making others sing, as they become, in fact, co-authors of this work.

What enables poetry to be replicable is the need to extend beyond the biographical aspects, to a beyond that is stepping into the shoes of an urban Ulysses. As opposed to the poetic absolutisms offered to us by tradition, which we have (unfortunately) grown accustomed to absorbing, Merola, in his vortex of spells, suggests that if the magic of poetry happened once it can happen again, provided, however, that we do not understand the formulas. Like the reader, the poet, must also allow him/herself to fall under the spell. What follows from the combination of these elements, is a sense of poetic replication, poetry as a sort of commodity: a market protagonist. If until now we have been taught that poetry is not expendable, that it is an elite artistic form and not very versatile, Merola challenges this notion this by offering a form of empathic writing that literally includes others in his song, to redeem them from being misunderstood.

Thus, Merola not only transmutes the meaning of journey into poetry (finally all can be written), but through movement, towards northern lands, with a compass gone insane, he lands at the doorstep of the fairy tale, of the idyll, albeit through pain, in this case. Once upon a time, the city of stars is a section out of time: a fairy tale in verse and a crucial one for falling under the spell of this collection. The poet sets the stage for the spell in a game where light and shadow pursue one another: the fairytale of a star and a man who are reborn on Earth sharing a single body, in order to attempt to lead astray a monster who is capable of laying siege both to the realm of fantasy and the plane of reality, “you asked: let us be reborn together. You didn’t know what it meant / to go back, to start over again.” Merola completes a katabasis, from the world of the stars to the foundation of a city formed by the stars, capable of illuminating a rejected, invented autobiography. It is a different one precisely because it is interpreted through the lens of a spell, leaving us at the mercy of an infinite sea, an ocean of emotions, as the line suggests: “but it’s not easy to trust, in the dark”.

Iuri Lombardi (Florence 1979) is a poet, writer, critic and dramaturgist. His publications include the novel Briganti e Saltimbanchi (1997), Contando i nostri passi (Romano, 2009), La sensualità dell’erba (Biondi, 2012), I banditori della nebbia (LFA 2019). His short story collections include Il grande bluff (Lettere Animate, 2013), La camicia di Sardanapalo (Talos, 2013), I racconti (Poeti Kanten, 2016); his critical writings L’apostolo dell’eresia (Faligi, 2015). His theater writings includeLa spogliazione, Soqquadro (Poeti Kanten, 2016 and among his poetry collections Il Sarto di San Valentino (Ensemble, 2018) He is a regular contributor to the literary journals Atelier, Carmilla, Poetarum Silva and Euterpe.