Going above and beyond literary values (often expressed in hierarchies) which are the keys of access to culture as a product of and for scholars, Dario Fo and Franca Rame have concretely defined, and continue to do so, a resurgence of the criticism of political power through their militant art of poetry and epic potrayals, as Simone Soriani states in his exceptional essay, Dario Fo, dalla commedia al monologo (Dario Fo, From the Play to the Monologue). This type of criticism, with its roots in the Middle Ages, exploded in Italy in the nineteen sixties. Fo and Rame’s criticism was, and still is, in social, esthetic, organizational and political terms, a challenge to the powers of the upper hierarchies of the church, judiciary and state, which constantly work to maintain the “city of the privileged” (including certain elitist aspects of the avant-guard theatre movements, most of which have decisively been institutionalized today). Accounts of public financing, the silence of those who have been shut out, and the science of language (including the sociology of literature and the semiotics of theatre) are the tools that have emerged to highlight the nexus between theatre and society, literature and social life, current events and dramatic action, and not to hide or outright deny this link, as is often the case. Still, the Nobel Prize awarded to Dario Fo and (indirectly) to Franca Rame has deeply scandalized many and continues to do so with impunity. It is evident by the grins, silence or open grumblings from the most old-fashioned and reactionary sectors of society. It’s probably worth our time to revisit the topic with the insistent reminder that Power has also strongly felt the temptation, or better said, the necessity to place ancillary figures between the actor, stage and public. This necessity is already evident in Hamlet, as Tessari wrote in one of his short but enlightening essays: “A company of actors banished from the big city, strays among a crowd of vagabonds, approaches the castle. The actors believe and hope they will be capable of entertaining the inhabitants of the area with their shows. They are welcomed, but the Prince who hosts them is not very interested in their repertoire. Better said, he wants to choose the work to be staged and, above all, it’s necessary that it be acted with a few important “corrections” which will serve his political scheme.” We know the story well. That which is important here, to us, is the fact that this episode places the Prince of Denmark not only among the historical beginnings of directing, but it also marks the first intimate steps of the modern rapport between theatre and politics. These first steps would be subject to the same “regulations pertaining to the Castle and its era and imposed as requirements of a primitive pedagogy meant to reform the art of acting” and, above all, its role in gathering approval; in other words, censorship by the powers that be.

What does the theatre put into practice by Dario Fo and Franca Rame consist of, if it is permissible to ask, when it collides with that of the official bourgeois theatre as well as with the emerging State funded theatre? This is evident right from the beginning, in the summer of 1953, when Giorgio Strehler and Paolo Grassi approved rehearsals for a seasonal production of Dito nell’occhio (A finger in the eye) by Dario Fo, Franco Parenti and Giustino Durano. The name of the play, among other things, coincided with the title of a satirical column written by Parenti, and quickly cancelled, found on the daily pages of the newspaper, Avanti.

We must not forget that these were the years immediately following the age of Vittorini’s Politecnico, closed due to irreparable conflicts with the direction of the Communist Party. This was also the time when Scelba’s right wing Democristiana Party was in power. It was within this context that Dario Fo and Franca Rame took the completely impassible road toward a new sociality of the actor’s theatre, with an objective not yet clear neither to them nor to others. As always, oppression was likely the key to delineating the boundaries and antagonistic weight of this new and divergent theatre genre. In fact, the 1951 debut radio show, Cocoricò, was censored in its eighth episode. The jaws of the vise certainly didn’t loosen with the passing of time, evident by a 1962 interview with Dario Fo in which he ironically responded to the criticism directed at him from everywhere: “Authors refute the claim that I am an author, while actors refute the claim that I am an actor. Authors say to me, you are an actor who writes. Actors say that I am an author who acts. Neither wants to identify me as part of their field. The only ones who put up with me are the set designers.”

It was during the years of Isabella, tre caravelle e un cacciaballe (Isabella, Three Caravels and a Blowhard) in which the critics accused him of not creating a shred of esthetic ideals (not even Brechtian). Yet, Dario Fo and Franca Rame mounted shows of great impact, derived from popular theatre, by employing theatrical resources taken from diverse genres such as variety, farce, mime, clowning, puppet theatre, cabaret, fables and folktales, comics, and silent film, thereby creating a diverse and unique dramaturgy that was indefinable and strongly marked by the permanence of its orality. It was by means of this orality that the genius of Ruzante (or Ruzzante for Fo and Zorzi) and the idealization of the medieval jester – in addition to the fully-developed farce and a theatre of comic mockery – intertwined themselves with the events of the day. In accordance with this perspective the actor creates and subjugates all elements of the performance – it is, therefore, a man of oral culture (from a contemporary standpoint) who takes the stage. When referring to the Nobel won by Dario Fo, one cannot ignore the conflict (even exegetical) between his entire body of work and the literary and theatrical standards in our country, including those found in certain progressive fringe groups. On one occasion, these fringes were even defined by the words of Franco Quadri at the beginning his volume entitled, Il teatro del regime (Theatre of the Regime), published by Mazzotta in 1976. In it, he states that “The urgency for a revolution of structures and expressive means has returned, first and foremost in relation to theatre, you understand, because, like a trusty mirror, the course of the microcosm of theatre reflects that of the Nation we live in…With some ferment and a little shake-up, we’ll drown the rising pool of reform.” These are true and just words, both then and now. It must be clearly stated that currently the city of the privileged, which Desmond Tutu already strongly highlighted years ago during a series of conferences in North America, is rooted on opposite sides of the spectrum; in both reactionary and progressive thinking, including their philosophies which were the tools used by opposing factions in the past.

In the case of Dario Fo and Franca Rame, their conflicts with the privileged sectors of society have always been clear, unmistakable and radical and cannot be translated as academic differences or placed in a simple esthetic order. Without listing the long series of trials, censorship, assassination attempts, and threats (which even went as far as the kidnapping and heinous rape of Franca Rame), it would be good to reflect upon the new kind of intolerance facing their work. Dario Fo and Franca Rame are the custodians of an extremely important social function assigned to them by a great popular following and over sixty uninterrupted years of a theatre of current events and politics. This is unique in the entire history of theatre and functions in accordance with a mandate that goes beyond ideology, while, at the same time, indisputably comprising it too. Together with the man of oral tradition, Fo is the architect of mockery and an anarchistic narrator who risks extinction by the digital era and the smart phone. The very same Franco Forti found among the most influential critics, poets, and intellectuals of the post-Second World War era, also displayed some opposition to the theatre of Dario Fo and Franca Rame. However, during a one on one talk with Fo at the Teatro Greco di Milano, Forti did see him as the ultimate Italian comic author. It is in Mistero Buffo, above all, that we witness a simplification of the ideas of Walter Benjamin, for whom comedy is the necessary internal upheaval of bereavement, which is understood as being the sufferance of a people or culture due to a loss of dignity or as a result of a fight for political identity. This is especially true in a strong and participatory culture, which is epic and centuries-old, and has its expressive roots in the arts and in the professions of the High Middle Ages, rustic culture and the small middle-class of artisans found in Italian hamlets. This type of culture lasted up until the late 1950s and was filtered through the philosophies of Gramsci and Marx.

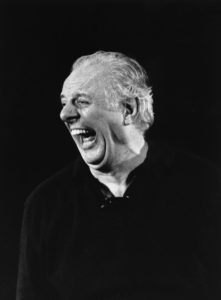

There is an interesting documentary – though dated and something to be re-watched – dedicated to Dario Fo and Franca Rame, entitled, Un Nobel per due (A Nobel for two), produced by Filippo Piscopo and Lorena Luciano and presented at the Venice Biennale. At the beginning of film, when the interviewer poses a question mentioning his recent Nobel Prize in Literature, Fo replies, “An Actor, I would like to presented, and thus remembered, as an actor.” So, Dario Fo insisted upon simply wanting to be considered an actor.

And, in my opinion, he is right because – despite his over seventy plays, now accompanied by several novels, memoirs, endless paintings and an important and recently updated acting manual – in addition to the form and content found in his theatre, or rather, their theatre, the two stand out for their way of seeing things and by allowing themselves to be seen. This is evident in the way the actor and actress physically transfer themselves into the text, how they modulate their voices and how they position themselves within the scenic space according to norms that welcome the emotions and intellectual reactions of a working-class audience. As was well explained by Bernard Dort, who we greatly miss, “Dario Fo has all that it takes to be an extraordinary mime. With a gesture of the hand, the arm, or the body, he knows how to unite those random movements that we never cease to give up. That which appears, however, is the inconstant and transitory figure of a man completely dedicated to history and class struggle.” Naturally, in order to accomplish this, it is necessary that the authorial and literary style employed by the performer is not one used by a pure and simple actor, but rather one of epic and expressive parameters open to the dynamic requirements of the audience members. Of course, this is certainly a variable only tolerated by the stagehands. “The only solution to the problem of theatre modernization would be to force the actors and actresses to write their own comedies or tragedies, if they prefer. Actors must learn to create their own theatre. What does the use of improvisation contribute? It serves to implement and weave together a text with words, gestures with current events, but, above all, it allows the actors to distance themselves from the deceptive and dangerous idea that theatre is nothing but literature.” This necessary aspect allows even the actors to be able pursue their own poetic aspirations and expressive dignity, according to the well-known definition formulated by Anceschi, for whom “poetics represent the observations artists and poets implement in their work by highlighting its techniques, operative rules, morals and ideals.” When it comes to techniques, operative rules, morals and ideals, we have to say that Dario Fo is the Master.

Waler Valeri holds an MFA in dramaturgy from MAXT/ART at Harvard University. In 1973, he founded Sul Porto magazine in Cesenatico, which dealt with cultural affairs in the province. He was Dario Fo and Franca Rame’s personal assistant from 1980 to 1995. In 1981, he won the International Mondello Literary Award for Canzone dell’amante infelice (Guanda). In 1985, he founded and managed the indie magazine, Il Taccuino di Cary in London. In 1990, he published Ora settimana (Corpo 10) with a foreword by Maurizio Cucchi. Walter Valeri’s books include Franca Rame: A Woman on Stage (Perdue University Press, 1999), An Actor’s Theatre (Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), Donna de Paradiso (Editoria e Spettacolo, 2006), and Dario Fo’s Theatre: The Role of Humor in Learning Italian Language and Culture (Yale University Press, 2008). From 2000 to 2007, he founded and directed The Cantiere International Youth Theatre, a project established in collaboration with the City of Forlì and The University of Bologna. In 2005, he published the poetry anthology Deliri Fragili (BESA). He has translated various works of poetry, prose, and theatre into Italian such as, A German Requiem by James Fenton, Carlino by Stuart Hood, Adramelech by Valére Novarina, The Blind by Maurice Maeterlinck, Knepp and Krinski, both by Jorge Goldenberg, and Nobody Dies on Friday by Robert Brustein. In 2006, he founded the international poetry festival Il Porto dei Poeti. His latest works include Visioni in Punto di Morte (Nuovi Argomenti, 54, 2011), Another Ocean (Sparrow Press, 2012), Ora settimana – second edition (Il Ponte Vecchio Press, 2014), Biting the Sun (Boston Haiku Society, 2014), Haiku: My name-Il mio nome (Qudu Publishing, 2015), Parodie del Buio (Il Ponte Vecchio, 2017), and Arlecchino e il Profumo dei Soldi (Il Ponte Vecchio, 2018). He writes for Teatri delle Diversità and Sipario magazines as well as for the online literary journal lamacchinasognante.com. He is also team member of The Poets’ Theatre of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

About the translator:

Marco Remo Zanelli holds a B.A. from Emerson College and an M.A. from Middlebury College. He is both a translator and Italian instructor, as well as an actor and director. He has translated theatrical, academic, literary, journalistic, and historical texts into English, in addition to television subtitles. He has collaborated with people and entities such as American Scientific Frontiers (PBS), historians Nicola Labanca and Angelo Del Boca, Equilibri, filmmaker Marcellino De Baggis, Paoletti Softdrinks, The Forum for the Problems of Peace and War and The Ivory Press, among others. As an actor and/or director, he has worked on Twelfth Night, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, A Midsummer’s Night Dream, All’s Well That Ends Well, The Three Sisters, on film productions and with various CBS, ABC, and NBC affiliates in addition to the NBC national TV network. He has also worked as a television promotion writer, producer and editor.