My first day in McAllen, Texas, I stand in front of the Ursula Detention Center, nicknamed, “El Refrigerador” by those who had been incarcerated there. I am participating in a demonstration in front of the detention center which blends into a strip of industrial corporate park buildings; neighbored directly to its left by “DanHil Containers: Manufacturers of Corrugated Boxes.” I watch a bus full of kids pull out of the detention center alongside protestors who have heart, but no superpowers.

I am traveling with Sean Tanner, an organizer from San Francisco. After a couple of weeks of watching terrified toddlers taken from their heartbroken mothers and reading about 1,500 children lost by the system, we are here to lend a hand to any organizing efforts and to report back what we see. Sean dives right into the protest effort trying to augment the ever-waning energy of protestors whose various signs and petitions at times existed in contradiction with each other. Degrees of demands ranging from radical to apple-pie reform. Another van with tiny heads in the windows follows the first bus out. I’m not sure whether strategically or poetically, but the van pulls out right as our cage walk of a march swings away from the gate. Some jog for a couple of steps or powerwalk a little toward the kids with a palpable despair, but it is too late.

One-sided war stories abound in the demonstration; the system standing in complete supremacy and absolute power over the people. For every one congress person who has gotten inside the detention center, thousands have been denied. The most we can do is provide services to any refugees released from detention or engage in symbolic intervention of military industrial business as usual.

People make speeches on a bullhorn. A heroic young woman fearlessly takes the bullhorn and declares that she is undocumented but will not be silent. She demands the release of all people (child or otherwise) and the abolition of ICE.

Some type of government agent stands outside the detention center with a camera that has what looks like a one-foot lens photographing protestors. One foot of lens to zoom in on sixty feet of activity. “Whoever wasn’t on the list before, is on the list now,” is the effect he is looking for, I suppose. Standing around next to the government agent are border patrol officers who are so comfortable in their operation that they are relatively benign to protestors. One soldier even tells us to not hesitate to ask them for help if a bad storm comes down. I think of an excerpt from a James Baldwin essay titled Fifth Avenue, Uptown:

Their [police officers’] very presence is an insult, and it would be, even if they spent their entire day feeding gumdrops to children. They represent the force of the white world, and that world’s real intentions are, simply, for that world’s criminal profit and ease, to keep the black man corralled up here, in his place.

Sean makes the news. And a protestor who wanted to sing the United States national anthem to the flag (or to the barbed wire blocking it?) makes the front page of a newspaper.

Militarized RGV

In the Rio Grande Valley, the military industrial complex is comfortable. South Texas is a softcore albeit less ceremonial and one-sided Korean DMZ. Even two or three hundred miles north of the border is a checkpoint where well-armed soldiers question our citizenship. Everywhere seems to be absolute open season on Latinx people. The border (military reality) sets the cultural tone, where other aspects of life seem like an afterthought. In Brownsville, Texas, home of the Walmart detention center for children there is also a community college using an old rundown mall for a campus. And while in fairness, UT Brownsville, fairly close to the border, was impressively-manicured, it does not put a dent in the militarized landscape.

The “international” bridge in Brownsville is rather unremarkable. You can take some pictures of random overpasses on rainy days throughout the United States, put them in a pile with the bridge at Brownsville and play a tough game of “which one is the border”. All that to say, they can make a border of anything. Just add some barbed wire, some soldiers, and a permanent enemy of color. The military edifices of the border (and the thousands of people they employ) look impervious to ballots. I wanted to run back and tell what I saw to the white activist in McAllen who (along with activated others) believed that Texas is actually a blue state waiting to happen if we could mount a zealous electoral ground game.

Feeding the shackled

There is a zealous ground game in South Texas. Built around services for brutalized people. Catholic Charities provide food, supplies, and respite to hundreds of ankle-monitor shackled mothers released from detention. Volunteers work tirelessly. A young man who daily makes food for the refugees gets choked up and unable to relate his own story of crossing the so-called border as a child. The community college professor who put Sean and myself onto the Catholic Charities at the Ursula demonstration appears now with his volunteer shirt on. He has been at it all day since the morning demonstration and will stop in the evening only to teach his college course.

Kidnapped asylum seekers looked exhausted and shell-shocked.

I did not have a translator and speak next-to-useless Spanish. In attempts at conversations with people I get fragments of image and sound effect. Children crying all night. Making two-month treks to get to border patrol abuse. People not being allowed to legally seek asylum and being forced off of bridges into the hands of soldiers calling them illegals.

RGV: Ideal locale for concentration camps

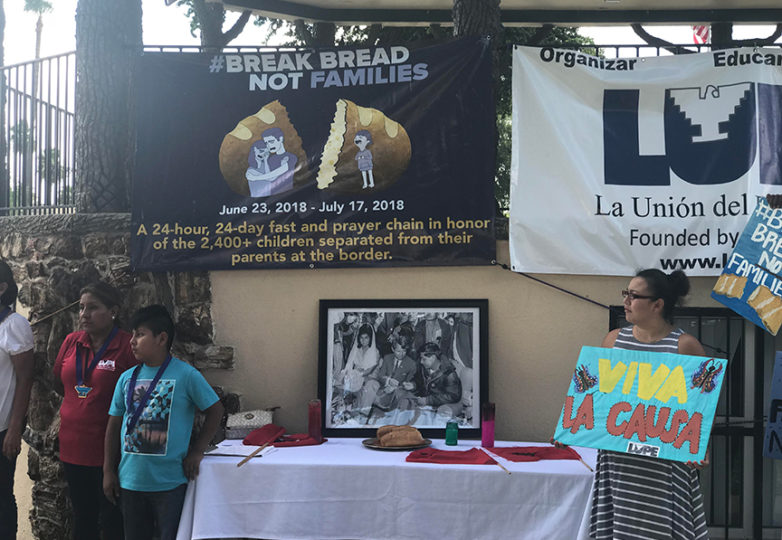

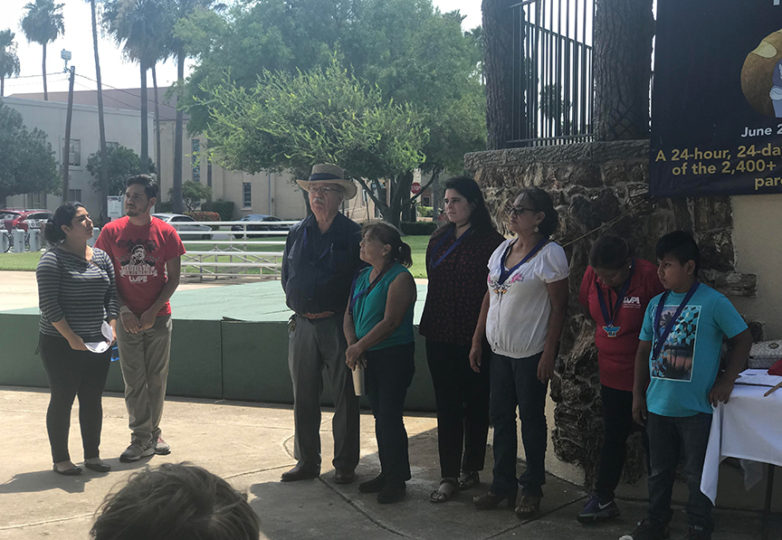

The next storm didn’t come, but the Rio Grande Valley was still recovering from a flood. Workers at the activist organization LUPE, founded by Cesar Chavez, told us it was hard to organize people when even the organizers couldn’t maintain stable housing. The RGV is the home of beautiful, perpetually destabilized people. A perfect place to erect and maintain concentration camps. The LUPE office is full of people looking for services, looking for survival. Even the most non-reformist, theory-directed revolutionary has to admit that people do immediately need a change of clothes, lawyers need translators, and people need to find and pull their families out of the jaws of the military industrial complex. A military industrial complex so fused with the prison industrial complex in this crime against humanity that maybe they were never not the same thing in the first place.

We stopped back through McAllen to chat with a woman I befriended working in a gas station. She had become a second home base for us. Sean and I stopped in the gas station during the Ursula demonstration to buy water for everyone and for some cosmic reason, at the counter, are small talk was big enough to discover that her son is getting a PhD in Literature, was a huge fan of the beat poets and by extension City Lights, and by extension knew and dug my work. In her opinion, the kidnapping of children, was not an escalation (of what has been going on in the RGV for decades) big enough to call this situation “anything new.” We wheeled back around to Ursula to see if the pediatrician, who had been camping out in front demanding to examine the children, was still there. Besides a couple of people with video cameras, the street was empty. Empty aside from the McAllen city employees who were painting all of the curbs yellow to make sure future protestors would have to walk from a lot farther to demonstrate in front of the detention center again.

The Struggle Continues

But an escalation of resistance may be coming. Some activists at LUPE, including the director, are ready for more direct intervention. Various people in various organizations related that it is the international bridges where effective stands can be made. But this will take more people. A lot more people than the RGV has mobilized now, especially given that the people mobilized now are incredibly stretched by all of the struggle they are currently trying to hold down.

We daily checked in with or were checked on by the folks who graciously put us up in the RGV. A friend of mine’s parents who made sure we wanted for nothing. They fed our confidence in the people and a liberation we must continue struggling for.

In south Texas, all I mostly saw was pain and the normalization of state violence.

The United States is at war with the people of the Global South. A war without terms. Neoliberal policies, global warming results, and direct political and military annihilation of political forces for the people and resistance to capitalism have produced a social environment so deadly that people would rather deal with abuses in the north than survive their repressed and exploited homelands. I don’t think anyone believes in American milk and honey anymore (if they ever did). People just don’t want to be shot. Imperialist violence is borderless. Our resistance must be the same. It must be international and politically clear on the entirety of the contradiction between the global oppressors and the global oppressed.

Link to original article in El Tecolote.

Tongo Eisen-Martin was born in San Francisco and earned his MA at Columbia University. He is the author of someone’s dead already (Bootstrap Press, 2015), nominated for a California Book Award; and Heaven Is All Goodbyes (City Lights, 2017), which received a 2018 American Book Award, a 2018 California Book Award, was named a 2018 National California Booksellers Association Poetry Book of the Year, and was shortlisted for the 2018 Griffin International Poetry Prize. In their citation, the judges for the Griffin Prize wrote that Eisen-Martin’s work “moves between trenchant political critique and dreamlike association, demonstrating how, in the right hands, one mode might energize the other—keeping alternative orders of meaning alive in the face of radical injustice … His poems are places where discourses and vernaculars collide and recombine into new configurations capable of expressing outrage and sorrow and love.”

Eisen-Martin is also an educator and organizer whose work centers on issues of mass incarceration, extrajudicial killings of Black people, and human rights. He has taught at detention centers around the country and at the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University. He lives in San Francisco.

Cover image: painting by Hassan Vahedi.