Born in Chicago, Louise Victor received her Bachelor’s Degree from Northern Illinois University in 1973 and her Master’s Degree in Fine Arts from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, in 1977. Admirers of her artwork may be astonished to learn that she spent much of her early professional life as a commercial airline pilot. In fact, she was only the second woman in the world to qualify as “Captain” of Boeing 757/767 aircraft. Despite her demanding responsibilities, she managed to develop into an accomplished painter, draughtswoman, printmaker, bookmaker, and curator of art exhibitions. The drama and power of her dynamic artwork clearly reflect her mastery of flight—both in the air and of the spirit.

Susan Aberg: Do you remember when and why you were first inspired to create art?

Louise Victor: I came to art early in life. During first grade, I was fortunate to be able to miss recess one day when my teacher, Sister Charlotte, asked to make a simple charcoal drawing of me. I don’t remember most of my childhood, but I do remember that drawing and my reaction to it. There, on the paper, was me! Not only was I startled to see my pigtails and freckles, but she had also captured more than what I saw in the mirror—something about me that was beyond my capability to put into words. I knew somehow that this was art. And, as I grew up, it became sacred, important, and special to me.

SA: Did your experience of art change as you matured? When did you decide to formally study art and why?

LV: As a teenager, I made renderings for an architect and fell in love with drawing. But, because the art I experienced and was taught in elementary and high school didn’t attempt to capture that “thing” that cannot be said in words, it didn’t have the same effect on me.

In college, I first focused on and declared history as my major, thinking I’d take a drawing course as an elective. But, because my professor, Nelson Stevens, presented art in the way I believed it should be taught—something that involved the inner self—I changed my focus and dove headlong into a lifelong study of art.

A Still Life

Oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches

Louise Victor, 2007

SA: What artwork most inspired your vision, shaping your artistic language, brushwork, and motifs?

LV: Without realizing it at the time, I followed the natural progression of history, beginning with Giotto, Byzantium, and Pre-Renaissance art. I became entranced with icons and the artist’s ability to depict a power and presence that is immediate, yet beyond comprehension.

After discovering how modern Giotto’s paintings are, I began incorporating their movement and energy into all my work. Taking the icon as his subject, he infused this divine object with humanity. His figures are massive, solid, earthly, and magnificent. They have choice and agency, showing both “God” and “mankind” as powerful. I’ve copied several of his works in many of my own drawings and paintings—so much so that I have them memorized: “The Massacre of the Innocents” (below), “The Entry into Jerusalem,” and “The Lamentation.” Giotto’s paintings have become the influence upon which I have built my entire practice.

The Massacre of the Innocents

Giotto

After Giotto, The Massacre of the Innocents

Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches

Louise Victor, 2012

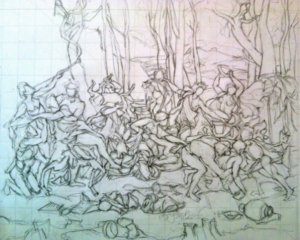

My interest then expanded to the 17th century French painter Nicolas Poussin, who continued Giotto’s exploration of flattening space rather than figuratively “drilling” into the canvas with perspective. Studying ancient bas relief, Poussin created a theatrical space that is energized and compelling, as in his “Rape of the Sabine Women” and “The Triumph of Pan” (below).

The Triumph of Pan

Poussin

After Poussin, The Triumph of Pan

Graphite on paper, 42 x 51 inches

Louise Victor, 2012

Modern painters like Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning were also inspired by the abstract pattern of the figures in this composition. With outstretched arms and legs, they form a wonderful central triangle composed of many smaller ones. Vertical trees in the background pull the figures skyward. Phases of compression and extension populate the canvas. It is the perfect composition, with exquisite movement.

Paul Cézanne then took Poussin and broke him open, changing the nature of space in painting. His handling of paint was nothing short of extraordinary! Everything in his pictures moves. I was also drawn to the linear freedom, brilliant translation of space, and emotional quality of the work of Arshile Gorky, the father of Abstract Expressionism.

Willem de Kooning—also an influence—was an admirer of Gorky, Cézanne, and Poussin. He used figures extensively and created magnificent pictures of complex figurations. Paintings he made before succumbing to dementia are stripped of all but the essential. I weep, standing before them. It is possible to trace his progression from these complex pictures to the transcendent.

My study of Milton Resnick’s work and Geoffrey Dorfman‘s book (“Out of the Picture: Milton Resnick and the New York School”) had a major influence on the way I think about painting. In addition, my study of Philip Guston’s work took my figuration to an entirely new level.

SA: Can you describe how art engages you emotionally, intellectually, spiritually, and physically?

LV: Art is sacred, revealing who I am and the nature of the world we inhabit. It is emotionally engaging, intellectually challenging, and spiritually enriching. It enables us to experience the ineffable—what cannot be expressed in words. Movement and rhythm are essential in my work. Everything in the world moves.

SA: When you’re alone with a blank canvas in your studio, how do you approach your first mark? Can you describe your imaginative process?

LV: Facing a white canvas is daunting. I first cover it with an underpainting, usually consisting of a solid color that reflects where I’m heading with the work. If I imagine a mostly warm composition, I begin with blue or green. If I’m thinking about a cool composition, I start with orange, red, or yellow.

Painting, for me, is all about process—the relationships throughout the canvas. The how and the why. After putting down a base coat, I draw the internal structure of the design with a brush—all the major verticals, horizontals, and diagonals. Taking a note from de Kooning, I then draw groupings that cover the canvas with figurative complexity. From this, I begin my painting in a process that’s subtractive rather than additive. I work into this chaos, creating order by simplification of forms. Working for a rhythm, tightening relationships, looking for compression and expansive movements.

White Lies

Mixed media on paper, 24 x 20 inches

Louise Victor, 2005

SA: Did your experience as a commercial airline pilot play a critical role in developing the dynamic movement, striking color, and powerful visual impact of your work?

LV: Yes, most definitely! I capture the essence of being in the air—the buoyancy, the release from gravity. Our world, our universe, everything is constantly in motion. I strive to capture the moment before the movement occurs.

Drawing, Landscape

Mixed media on paper, 30 x 24 inches

Louise Victor, 2005

Resnick describes that effort as an artist capturing the moment by “stopping [an object] from falling.” If you imagine a ball being tossed, there is a moment when the ball is not moving upward or downward. It is in neither place, but buoyantly moving with the air. That is the moment between the breath, when your being is hovering in space.

Exits and Entrances

Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches

Louise Victor, 2019

Flying airplanes taught me how to think about life and understand it. Studying every detail of an airplane and its systems can be very complicated. But if you take the pieces apart and put them back together, one by one, you can learn how they work individually and in relation to one another.

The same principle applies in art. I believe that drawing is the basis of all visual art and that anyone can be taught how to draw. But drawing is more than just a tool for capturing likenesses. It is a language.

Learning to draw is about learning to see. Whatever its form, drawing transforms perception and thought into image and teaches us how to think with our eyes. It is learning by hand. It is muscle memory, something that—when I started flying—proved to be true in more than just art. You take something apart, examine each piece separately, and then combine them with every other piece you’ve studied. They fit back together like a jigsaw puzzle.

Everything is about its relationship to everything else. And this is how I think about my life. I am a piece of the puzzle and, depending on my talents, I must fit in with all the other pieces and people that form the whole picture. Everything moves, and everything is about relationships.

SA: Do myths, memories, dreams, and other narrative sources inspire your artistic imagination?

LV: Myths, most certainly. Also poetry and fairy tales. And memories of the senses are essential in art. If you are immediately attracted to a work of art, it may remind you of a distant memory.

SA: The structural foundation of some of your artwork is formed with lines, sketches, scratches, and brushwork beneath the finished piece. At times, you use multiple media (thread, for instance) to knit portions of an image together. How do you construct something so imaginative and expressive, layer by layer?

LV: I build a picture and then “excavate” back through it to reveal the initial impulse. Constantly drawing and redrawing. Line is the language we use to translate our three-dimensional world onto a two-dimensional surface.

At the Edge of the World

Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 inches

Louise Victor, 2021

I think of life as an entanglement of lines, relationships that build a society. And these play a prominent part in my work.

The Language of Trees

Oil on linen, 36 x 24 inches

Louise Victor, 2022

Paul Klee famously said, “Drawing is taking a dot for a walk.” And I agree. A line is time, process. As a pencil moves forward, it leaves its past behind. At this moment, it is the present with infinite possibilities of where to go next. Whichever way the pencil moves brings a new act of creation.

That is drawing. We draw to learn how things work, how they go together. Relationship permeates our lives. That is how I think of the world. Everything is held to everything else by lines and an entanglement that is the very fabric of our lives.

SA: How do you know when a painting is complete? Do you continually “improve” paintings, reworking them even years later?

LV: I believe in the process. I usually do not consider anything really finished. If I see something that needs changing, and it is a work that I believe is worth it, I will do so—even years later.

SA: In addition to numerous solo and group exhibitions, you’ve been commissioned to create art for books, manuscripts, and public settings. Can you describe what it’s like to come across your work out in the world?

LV: That experience is both exciting and confusing. If I don’t anticipate seeing it, I’m not very quick to realize it’s mine. I often use this same sense of surprise as a check on my work. I deliberately won’t look at it for a while and then, when I see it at my studio or in another setting, I register my first impression. That way, I can either sense changes that need to be made or accept it as is.

SA: When did you start teaching art? Has that affected your own practice of creating art?

LV: I love teaching and believe it’s important to pass on information gleaned from experience. When I was flying, my Chief Pilot encouraged me to evaluate pilots who are taking their first flight in new equipment or a new position. My father, who was also a commercial airline pilot, repeatedly reminded me not to fly an airplane if I believed I knew everything there was to know about flight. His warning was a lesson in humility, but also in remaining open to new experiences.

I began teaching art about 15 years ago, which I love to do! The interesting thing, as any teacher will tell you, is that you learn from your students. I’m constantly learning, thinking of myself as a student of life.

SA: Do you have any idea about what you may be exploring next, artistically?

LV: I’m constantly exploring, questioning, and thinking about what can be done artistically, what I’ve already accomplished, and how best to depict what I intend and need to say. “Encounters” is the title of my new series—a visual representation of life’s struggles. What does it mean to be a thriving, vital community? I believe we need a counterbalance to the dread, anxiety, and evil that is bearing down upon us. Even though we can’t expect to defeat the absurdities of the world, I feel compelled to create visual representations of basic human decency.

Refugees II

Oil on linen, 24 x 36 inches

Louise Victor, 2022

SA: Thank you very much, Louise, for sharing your thoughts, insights, and inspirations. It’s been a delight to learn about your creative journey!

Victor serves on the Board of the Industrial Center Building (ICB) Artists Association and teaches at The Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. In addition to leading both private and group studio courses and workshops, she has lectured at Arts Benicia; Gallery 111 in Sausalito; Jen Tough Gallery in Benicia and Santa Fe, New Mexico; Marin Museum of Contemporary Art in Novato; and Mythos Fine Arts Gallery in Berkeley—to name just a few. For more information about her: https://www.louisevictorart.com/

Susan Aberg: With a degree in Art History (BA, UC Davis, 1978) and studio classes from Sacramento-based artists Lois Upham and Wayne Thiebaud, Susan interned at Richard Nelson Art Gallery (Davis), E.B. Crocker Art Gallery (Sacramento), Oakland Museum, de Young Memorial Museum, and Maxwell Art Galleries (San Francisco) before becoming a production weaver in the Bay Area and launching a career in event planning at the University of California, Berkeley. In 2012, she created the online art community, “Art is Life.” See: https://www.thedreamingmachine.com/art-in-the-time-of-pandemic-from-quarantine-to-community-susan-aberg/