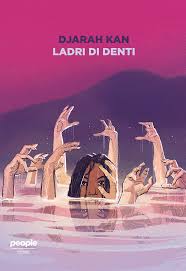

Cover photo, courtesy of Modio Media.

As a writer, I consider the main task of poetry to be the hearing and feeling of time, and the attempt to find appropriate words for it. Because each time has its own vocabulary, its own language, its own intonations. But what is it— this time in which I live?

All my life, I’ve lived among conversations about the past. Repressed history and private memory, the “stolen 20th century” (that’s how Ukrainians talk about their lost chance to gain their own statehood, 100 years ago), murdered Ukrainian culture, Holodomor, the Holocaust, war, deportations, another war, war again. While our closest neighbors are discussing waste sorting or the challenges of the climate crisis, Ukrainians are trying to tell their own story in their own words, from the point of view of a Ukrainian subjectivity and agency. Like any people with a long history of enslavement, we know well what it’s like not to have a voice. Even at the level of the right to our own language. Because Russia as an empire banned the Ukrainian language for centuries, and when it did not officially ban it, it tried to convince Ukrainians that our culture was provincial and rustic, and the language is ridiculous, peasant-class and second-rate.

All these conversations are tiring. Talking about these topics again and again, you feel like a dog on a chain, which drags the booth to which it is chained everywhere it goes, making an incredible noise. All these conversations are like chewing gum, which we transfer from mouth to mouth, as if giving ourselves artificial respiration, and we cannot spit it out, get rid of it, overcome it.

Today, perhaps for the first time in my life, I live in the present tense. It would seem that this is a step forward, towards the future, the dreamed future. But it turns out that living in the present time is terribly uncomfortable. Because the wind of history is like the wind from the Judean desert in winter, it is icy, eerie, and constantly knocks you down. It turns out that even one step into the future is taken with blood, sweat, tears and pain. And being a witness and a participant to the moment when the clock of history freezes on the threshold between winter and summer is not a very pleasant job. War really stops time. Living in Ukraine today, you cannot plan any further in advance than one day. No Ukrainian, falling asleep at night, can be sure that he will wake up in the morning. And Ukrainian children, our embodied future, do not have the opportunity to get a normal education, because during every air raid they have to go down to the shelters. Of course, we have built underground classrooms for them, as, for example, we have done in the Kharkiv metro. But do these conditions contribute to the full development of the personality, the mastery of new knowledge, and allow for fair competition with those who have had the opportunity to study normally?

Today, the horizon of Ukraine’s future is littered like a bad amateur photograph. Peering into it, you see a darkness in which you can hear the hum of an Iranian shaheed or the rustle of a Russian rocket. Because it turns out that even when it seems that the future is already here, that it is already standing in the entryway of your house and knocking on the door, just behind it stands our past. It turns out that our past is a sniper, constantly aiming at our backs when we try to escape from it, like escaping from a ghetto or prison. A sniper with the passport of a citizen of the Russian Federation. Because Russia’s war against Ukraine is a war for the past, which has only one goal – to make the past great again, despite the fact that this past was a life without rights, in a concentration camp measuring 22.4 million square kilometers.

Living in Ukraine today is like running in place, hoping that one day you will finally see the finish line. Or as though we have fallen into a river, where we are swimming and drowning at the same time, desperately gasping for air, with lips cracked by fatigue. Tiredness is the word that conveys the feeling of time today. Fatigue is the word that will convey the feeling of time in Ukraine tomorrow. Because even after the war, we will face endless economic, social, environmental, psychological and health problems that many generations to come will have to deal with.

Fighting for the future and living in this chosen future is hardly possible at the same time. But do we have a choice?

On the one hand, we have no choice. On the other hand, Ukrainians have already made this choice – they chose freedom. “Independence or death” – that’s what the Ukrainian Cossacks used to say when they went to fight. This is what we, their descendants, say today, confirming our own responsibility for the choice we’ve made. Yes, Ukrainians are not living the lives we dreamed of during childhood. Someone – volunteering in the rear or in the first line, someone – dying and being wounded at the front. When I think about this, I remember Margaret Garner from Toni Morrison’s «Beloved», who killed her child so that this child would never grow up to become a slave like her. Ukrainians need no explanation to know why she did it.

The Russian-Ukrainian war has been going on for 9 years now, and I am writing about it. Sometimes it seems to me that this topic has captured me, and I will never be able to free myself from it. But the age in which I live is a time of war, suffering, and pain, so I just try to do my job honestly. Because even if you can’t choose the time you live in, the freedom to choose the words to describe that time is already of great value, already a great privilege. I don’t know if this freedom of writing gives hope for a better future, but at least it allows me to describe the present and give future generations the right to choose whether they want to live in the world I live in today.

This essay was read at the Iowa City Public Library during the International

Writing Program panel discussion “Future Perfect” on October 15, 2023.

Poet, translator, and journalist Iya Kiva was born in Donetsk in eastern Ukraine. In 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, she was forced to flee the Donbas region, and became a refugee in Kyiv. In 2022, with the large scale invasion by the Russian Federation an d the ensuing war she was once againdisplaced and moved to Lviv.

Kiva is the author of the poetry collections Podalshe ot raia (Further from Paradise, 2018) and Persha storinka zymy (The First Page of Winter, 2019) and a nonfiction book on Belarusian writers, My prokynemosʹ inshymy (We will wake up to others, 2021), all of which were listed as best books of the year by PEN Ukraine. Her other honors include the All-Ukrainian Poetry Competition Malachite Rhinoceros, the Nestor the Chronicler Prize, and the Metaphora Translation Prize. Her work has been translated into many languages.

Kiva writes in Russian and Ukrainian and translates from Russian, Polish, and Belarusian. A member of PEN Ukraine, she has served as laureate of multiple international and Ukrainian poetry festivals, and her poems have appeared widely in literary journals. Kiva’s writing has been translated into English, Polish, Lithuanian, French, Ukranian, German, and Czech. She lives in Kyiv.