Yves Bergeret’s “Bio-bibliographical Note”

February 15, 2021

I am asked for a “complete an up-to-date bio-bibliographical note”. It’s a common enough request: professional activities with start dates, a list of books with dates of publication. Such piece of writing is based on the following assumptions: writer (but, how do you define one?), book (but, what is that?), publication (and what should that be?). There appears to be a consensus on these three concepts. Let us note, however, that my “intellectual itinerary”, has always intended, and actually managed, to engage in a dire manhandling of the three concepts above. And not without good, substantive reasons.

Be that as it may, I shall try to provide some answers in the document below.

Whoever may want to get a ‘proper’ “bio-bibliographical note” referring to me and my work, can always skim this piece of prose and keep only titles and dates; however, if they had the patience to read this piece carefully, they couldn’t help but conclude that such process of selecting information would only yield an odd and inadequate outcome.

Mountains

I was born in 1948. My education? Mountains, mountains and more mountains. Firsts walks alone around 8 years old around the village of Saint-Nizier du Moucherotte, in the north of the Vercors, in the vicinity of Grenoble. Village completely destroyed by the Nazis for acts of Resistance in 1944. Then, multiple hikes or even climbs alone in the Belledonne massif, east of Grenoble from 12 to 18 years old. First high mountain climbs (in technical mountaineering gear) from 15 years old in the Oisans massif. Then multiple climbs, always first of the roped, high level, Alps and Pyrenees, including in very wild, secondary massifs.

Always a volume of René Char in my backpack, from the age of 14. And even today.

Left ankle fractured and sprained in 1970 just as I had passed the recruitment competition to become a mountain guide. No family wealth.

Forced to switch to literary studies: hard work for the whole following year as I attempted and succeeded in passing the extremely grueling and repulsive (in those days) national competition to become a Classics teacher. René Char still on the table, to avoid asphyxiation!

In 1972, due to my firm refusal to bear arms, I request to be sent as international cooperating teacher to a mountain town in a mountainous country: I am appointed Visiting Professor at Moscow University! Two, extremely difficult years, frankly speaking, as the country was undergoing full re-stalinization. However, I quickly became acquainted with dissidents and “independents”, including composer Edison Denisov (fifteen years later he was to create a work for twelve acapella voices, Légende des eaux souterraines, based on poems from my collection Sous la Lombarde. When he moved to Paris and then settled there, I would visit Denisov regularly, until his death in 1996).

The mountain speaks

In the summer of 1977, I was leading a mountaineering expedition in the Hindukush region of Afghanistan: the average age of our group of climbers was 30-year old. First marriages, first children, various professional obligations, to make it short, soon there would be no time left for an over six thousand meters climb. In the summer, only this part of the Himalayas is not affected by the monsoon. Total mayhem: here the mountain is alive. As opposed to the Alps where the high altitude environment has been left to its own devices since World War I causing the disappearance of animist sacrality, hamlets laying in ruins, rituals erased, anthropology stunted and converted into in an Anglo-Saxon Puritanical sports cult (“the homicidal Alp, challenging oneself, conquering the mountain, the conquerors of the useless, etc. ” destined to further deterioration in later years by the competition unleashed by sports equipment dealers and their frenetic ski lifts). In contrast to that, the high valleys of the Hindukush are densely populated, multiple rituals and languages are alive, as well as inter-village conflicts, Buddhist or animists space markings are alive and well everywhere. I put my technical mountaineering equipment away now, as they are devoid of meaning.

Summer 1978 impossible to return to Afghanistan due to yet another coup: under the cover of a sports visa, I had intended to listen to what the mountain people of Panjir and Nuristan have to say. I spend the whole summer in the mountains around Briançon. What a splendid time that was! One day a solo climb to a summit on the Italian border; for each climb I write a simple poem about it. All these poems would eventually make up the collection Sous la lombarde (as we say in Briançon: under the “Lombard wind” which blows on these peaks), published by Caractères, March 1979, my first book.

Georges Dumézil, anthropologist specializing in Indo-European myths and religions, writes to me on the subject of my book saying that it is pervaded by an unusual epic feel; we meet multiple times.

.

Several small publications follow shortly thereafter. In 1980, just by chance I send Gallimard the manuscript of Territoire coeur ouvert. It is published together with unpublished poems by five other poets in a Cahier de Poésie 3, a collective series for new poets, which was later to be discontinued by the publisher. Among the other five poets, I discover Monchoachi.

Life of collective poetry and resistance

In those years I teach high school including one in the north of Burgundy, which offers a fascinating course in typographical printing; in the small town, I listen both to young poets and not so young ones. I set up a small poetry press, Les Cahiers du Confluent, and help circulate the work of French and foreign poets by subscriptions, keeping the project alive for ten years. At the same time with the help of the City administration and the enthusiasm of the young poets of the region, I establish a very active local “poetry club” with annual publications, an annual festival and, in the first year, a spectacular poetry exhibition-installation containing poems generated by this “club” and painted in a very large format on banners by a decorator with calligraphy skills from the municipal technical services office. The poems are hung in the courtyard of a gorgeous medieval farm, which was later to be turned into a museum.

Overwhelmed by the enthusiasm of the poets of this region, I am forced to move.

I am then offered a position as cultural attaché at the French embassy in Prague, and my post as director of what was to become the French Institute in Prague carries a significant budget. I start the job on 1 September 1988. In Prague the Iron Curtain is impermeable, Havel is in prison. Despite the difficulties and thanks to a sort of tacit complicity on the part of a few apparatchiks, in November 1988, always in Prague, I set up the first ever performance of Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape. As a tribute to Char, in February 1989 on the first anniversary of his death, I set up a staging of Boulez’ The Marteau sans maître on poems by Char concomitantly with an exhibit of Char’s Lettera amorosa, with the 27 lithographs by Georges Braque.

Contacts and planned actions with underground university seminars. Multiple events offering Czech and French contemporary poetry, music and visual arts.

At the end of November 1989, the Velvet Revolution. My mission in Prague ends in the summer 1990.

Unfortunately, life in Prague slips into fashionable, media driven trends; Margaret Thatcher-style ultra-liberalism destroys any budding ferment in the arts and publishing.

In 1988, my Voyage en Islande is published by Alidades editions: poems based on daily experiences in places like Greece, Leningrad, the Alps, and especially in Iceland’s black, volcanic deserts.

In 1992 my Poèmes de Prague is published by Le Temps qui fait.

West Indies and language-space

In 1991 and for the subsequent ten years, I am appointed commissioner of the Pompidou Center in Paris (today we would say “curator”, it is in fact a high level administrative post in charge of exhibitions and conferences, catalogs, etc.).

Since I deemed the “chamber “ and “Ivory tower” poetry still fashionable at that time, as well as hyper-formalist poetry, to be sterile pursuits, I orient almost all my activities towards poetry produced in Black Africa and the West Indies. In Martinique, I meet Aimé Cesaire and get to know Monchoachi better by working directly with him. Even in Paris, I keep company and exchange ideas with Lorand Gaspar and André Frénaud.

Many trips to the West Indies, multiple volcano climbs.

In February 1996 a life-turning experience in Guadeloupe: on the ocean shore a homeless Black man used a desultory piece of red sheet metal, held together by a few wires, to block the access path to his scrap-metal “hut”, whipped by the trade winds. He is not there. His sheet metal is belting out its song together with the wind. It is a mirror held up to whoever arrives there: “Me, an uprooted, descendant of slaves, I squat in front of my lost Africa on the other side of the ocean. But you, who are you, who walks here? think about who you are and give me your reply “. This was obviously the question posed by the language-space of this place, this place where until 1848 slaves were deported to for the exploitation of sugar cane. For me, this is the occasion that defines with utmost clarity the concept of language-space.

All space belongs to language; even when it appears to be submerged, language is never completely extinguished. Space is the set of human signs sedimented on a given spot; many of these signs are questions. A poem is the answer that I suggest to the question posed by a given place. The poem itself is part of that space.

In that same year, 1996, I am invited to teach the “poetry and space” course at Paris 1, as part of Plastic Arts faculty. I do it a few years. At the same time and to this day, I participate in multiple seminars and conferences, both in France and abroad.

Various pieces published (for example the Martinique collection, 1995, L’Estocade editions, Nancy), installations, articles, performances, up to Fer, feu, parole in April 1999- a group of eleven poems “installed” with metal sculptures by Martinican artist Christian Bertin, starting from the shore all the way to the top of Mount Pelée, the island’s volcano. Nightly reading-concerts of my poems which are displayed in a very large format, scattered and deployed on the ruins of the town of Saint-Pierre, completely destroyed by the 1902 volcano eruption; the entirety of this vast work is an active homage to the spirit of the fleeing slaves and Resistance, anywhere.

The core of the prose and poems making up Fer, feu, parole is included in my collection Volcanoes, Cadrans editions, June 2014, Paris; this book also brings together my readings related to the language-space of the volcano on Reunion Island in December 2013, and Etna during the hugely popular festival of Santa Agata in February 2014, as well as various other studies related to my work as a poet drawn to volcanoes.

The installations at Montagne Pelée and in Senegal

Starting from Fer, feu, parole in April 1999, most of my work as a poet is no longer accomplished through publishing books: it takes place outdoors and in action, in unconventional formats and on non traditional supports, and is always in conversation with the language-space of the location.

Unlike land-art, I always maintain the poem or the poetic aphorism at the heart of the installation and avoid any abstract aestheticism that excludes the local inhabitants. The core of my difference with Fluxus is that I do not question the work nor the language by deploying a critical shift bent on endless deconstruction. On the contrary, my work always crystallizes the humanity of the place, in its most ethical and memorable dimension of all, i.e., the poem. The poem is deployed as dramaturgical word-in-action moving through space. Outside of Europe, it is action supported by local, popular musicians, while in Europe it is supported by musicians capable of improvising contemporary musical genres on violin, flute, cello, percussion, saxophone, clarinet, etc. (starting from defined themes, resulting from non-public rehearsals),

Though extremely rich and the locus of incessant conflict, Caribbean language-space is forever mourning the loss of its Black African roots. So I want to listen to this, arguably, even more radical language-space. In 1998, my interventions at the School of Fine Arts in Bamako. In 1999 writing workshops in Saint-Louis-du-Senegal, but still in a deeply colonized environment. I transform these workshops by inviting Wolof canoe painters, despite the protest of half of the attendees and the enthusiasm of their other half. Coup de theatre: my workshop is met with great popular acclaim. Six months later, it is followed by a very large exhibition of the poems that I have come back to create on site with four canoe painters. The notion of “placers of signs” originates at that time: the signs placed on either side of the canoes are not decorative, they act by validating the fishing trade which kills the children of the ocean goddess to feed the children of the fishermen who put their lives at risk while working on the canoes.

Word-in-action is reality, Koyo

Feeling the need for the mineral space provided by mountains, which is my origin and substance, in the summer of 2000, I go to the Sahara mountains in the north of Mali.

A desert? Not at all! Except for the very rare aristocrat, the illiterate people who live there are steeped in orality and though they live in utmost material poverty, they have elaborated extremely rich thinking and practices related to space. Practically, I have no idea of who they are; but I gradually discover it.

First of all, I want to meet “the placers of signs” a few at a time. Then, I want to observe and try to understand and, finally, if possible, enter into conversation with them, about what this poem is saying, in response to what, what we return to the space that we listen to, and who questions us.

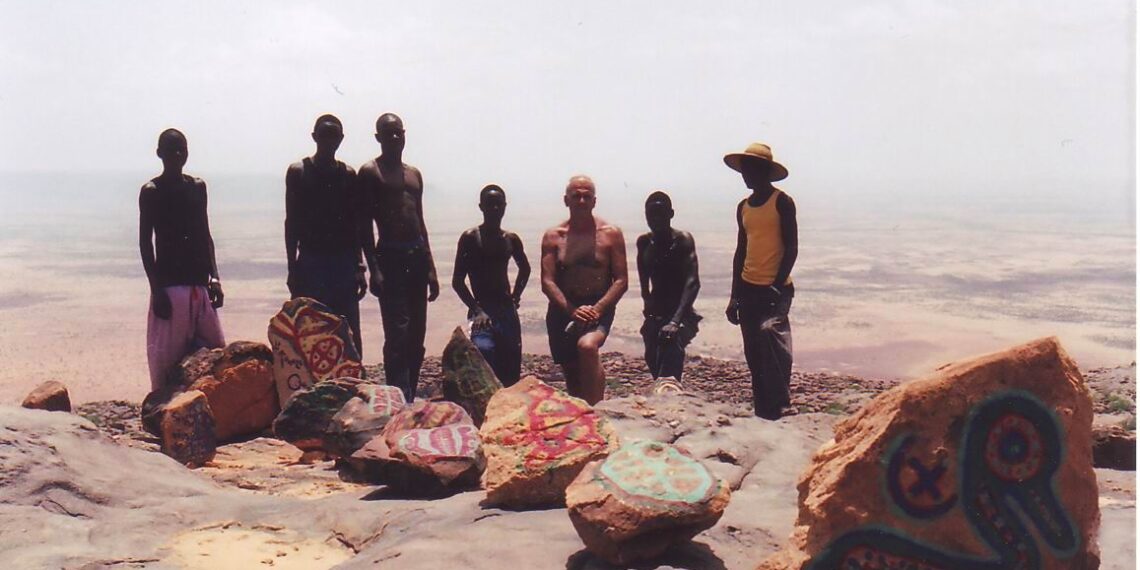

At the beginning of August 2000, I found myself in a very delicate situation: welcomed by a Tuareg tribe (Berber people, white skin) a restless and bloodthirsty people, I start getting interested in their “placers of signs ”, who are their slaves, of course Black. Strong tensions with camp leaders. I am barely able to get out and cross the river again fleeing to the south of Niger. I arrive in the sandstone mountains of Hombori: first “houses painted on the inside”. After several weeks I arrive in Boni, many houses painted especially by Fulani slaves, in Nissanata and Nokara and most of them, at the top of a mountain and accessible only by climbing, in the village of Koyo, which is self-managed and self-sustaining.

Twenty-two long stays in this village are to follow over the course of ten years. I gradually learn the language of the village, receiving many initiations. Koyo belongs to the Toro Nomu people, the most easterly of the nine so-called Dogon peoples (this name is a fictitious invention by French colonialist ethnographers in the years 1935-70; in fact each people speaks a different language, their rituals are far from being the same). Koyo vigilantly protects itself from the nomadic slavers of the sandy plains: in this region these nomads are mainly Fulani (peul) , rarely Tuareg. Koyo’s ontology considers that the whole of reality is made up of the word which is dense and stable in its rocky form, loose and elusive in its sandy form, etc. This ontology is developed through many rituals and myths and transmitted in initiatory orality. And after showing me superb murals painted inside some of the houses, during my second stay in the village I suggest that some of these “placers of signs” pronounce together with me the word of the place and place it – they with graphic signs and me in the Latin alphabet on the mobile support of fabric or paper (hitherto unknown) and on flat stones that we bring up to the place. I didn’t know then if this proposal was appropriate for the thinking of the village.

Each poem was made with four hands (and even with fourteen hands for the stone installations and for larger fabric ones) and understood in the following six step process, which was developed starting in the early years: 1 / long walk on the plateau’s summit, that is to say in the density of speech, which is of course animist and, therefore, sacred; 2 / choice of a specific and mythical place at the end of the walk, selected by the “sign placers ”, in order to create together the poem of the place; 3 / creation of the work, generally in acrylic: 3a: the “placers of signs” ask me to paint the poetic aphorism of the place, I translate it [soon enough I speak the language] then an elder, more advanced than me in initiation, in turn translates it; 3b: the “placers of signs ”invent (the toro nomu people have no writing) and paint their signs graphically then they tell me to “write on my little notebook what they wrote” (sic) [thus the ethnological transmissions increased considerably in number and became deeper]; 4 / one night per week the sacred group of eight Female Elders of the village sing-dance in a central square in the village “what we have said and done”, giving our work access to the reality of ontological speech; 5 / the mobile works on paper and fabric stored in my backpack arrive in Europe for a large number of exhibitions or interventions, which generate some earnings (the most important exhibition takes place in summer 2005 at the Museo Nazionale Etnografico Pigorini, in Rome; hence a complete bilingual Franco-Italian catalog: Montagna e parola, Gangemi editions, Rome, 2005); 6 / upon my return to the village a few months later, I deliver the earnings from our work, give it both to the “placers of signs” who proceed immediately to form a cooperative, and to the village for the development project it has drafted (including the doubling of the size of the vegetable garden areas by building four water reservoirs, etc.). And the six-step cycle described above starts again.

This is why the resulting poem has absolutely nothing to do with an elegiac confession written on a sheet of paper, or with some refined form of social retreat, or with some mocking verbal play on language, or with some precious narcissistic lament, etc. The poem is not cut off from reality by bitterness, spite, nihilistic failure or aristocratic disgust; on the contrary, it acts in and on reality and enhances it. The poem is an act in a long initiation process, and as such is constantly responsible. It is constantly deepening an ontology or even a metaphysics of words-in-action. The poem is a living part of the constantly fertile language-space. The notion of “author” disappears; the poem-in-action is the fruit of a collective, conscious work whose written dimension is merely epiphenomenal and whose deepest anchoring in the real is the final, choreographed song of the Female Elders.

Several publications on this subject, including Si la montagne parle (If the mountain speaks) , published by Voix d’encre 2004, and especially Le Trait qui nomme , bilingual Franco-Italian, Algra Editore editions, Zafferana Etnea, 2019.

Europe: Galicia, Cyprus, Sicily

At the same time and since 1993, I was invited to do many performances, installations and interventions in Europe, air travel being short and easy.

It is always related to giving a reading of the “language-space” of the place and creation of a conversation, if possible, with it.

From 1992 to 2001, reading of a space and the signs that make up language-space in the mountains of Galicia, around Lugo, on the edge of the Asturias. Many poems and installations in very impoverished villages that have increasingly become deserted due to decade long emigration to South America; numerous fundraisers with Anxo Fernandez Ocampo, the Galician researcher from the University of Vigo. Great exhibition at Museum of the Galician People in 2001, in Santiago de Compostela, titled Stone signs and levees after the book, in collaboration with Anxo Fernandez Ocampo, bilingual Galician-French edition at Publications de University of Vigo, 2009.

From 1993 to 2009, space reading of the island of Cyprus, where the language-space is enclosed in a sort of cruel turbulence, between the prevailing Orthodox nationalist Hellenism and pressure from the Turkish Muslim. Worse yet, the rare artist and the rare people of conscience who can no longer resist the commercialization of Scandinavian and German tourism are forced into exile in Greece or England. Poems and installations with contemporary musicians including Mediterranée with Faidros Kavvalaris, 1998: a one-time event. Anyway, bilingual Greco-French publication of L’image ou le monde, published by the French Cultural Center of Nicosia, in 2008: analyzes the frescoes inside eight medieval chapels in the Troodhos mountains.

From 1996 to 2019, space readings in Sicily and numerous attempts at creating a conversation with its language-space. The island, seismic and volcanic, is unfinished and has still failed to stabilize its use of the word into dialogue and trust. Feudalism and omertà are still in command there. Words never mean a commitment for those who utter them, and are immediately undone despite a great show of gesticulating that recall the puppet theater. Most writers and thinkers, often deep ones, migrate to northern Italy. In 1996 I was invited to Noto by the editor of Martinique: my first contact with the island. Of course the volcano, Etna, attracts me; over the years I was to climb it regularly and sleep there under the stars. There I make calligraphic poems- large format paintings; I convey them to the public in various places, theaters of Catania or Baroque ruins on the southern hills around Noto, with installations and live music. The musicians were truly remarkable, almost all them were to leave later, emigrating to the north of the country.

Works from this period include: L’ile parle brief poems I engraved or painted on 60 ceramic pieces prepared by ceramist Andrea Branciforti, Caltagirone, then Catania, then Venice, 2007, L’ile parle, with two percussionists, Catania, February 2010 Poem de L’Etna, (an important work) with a percussionist, Catania, October 2010: no fear of the monstrous power of Etna, a terrifying metaphor for feudalism and omertà L’os léger, Noto Antica, June 2013 La Voix du sol, Noto Antica, October 2013.

Suddenly in summer 2014, in the heart of Sicily, in a village called Aidone, I meet migrants who had arrived illegally from the Sahel, like those to whom I had already devoted La mer parle in 2007. They encompass all the anthropology and the considerable language-spaces that I became acquainted with since 1998 in Senegal and in the desert in the north of Mali. Heroes who have crossed the Sahara, Libya and the Mediterranean at the risk of their lives, always in solidarity and extremely dignified, truly faithful to their word. Such a striking contrast, (as original as fertile, I f hoped early on), with the local language-space which has been mutilated by massive corruption, permanent fear, the most elusive omertà: this desolate language-space of the hills, though aesthetically very beautiful, from the center of the island. In 2015, I started a writing workshop with four migrants. The local power brokers quickly get irritated with me and end up communicating their annoyance to me physically. In 2017, I publish Carène, a vast, five act, French/Italian bilingual dramatic poem, on this subject. Algra editore, Zafferana etnea (in Sicily). Carène is staged in a theater in Catania in December 2018 under the direction of Anna Di Mauro. From this time on, ‘someone’ in the island creates big problems for me.

A small group of priests with Marxist tendencies living in the center of the island supports me. The Sicilian publisher too, with enthusiasm. He is the one who in August 2019 publishes my large, French/Italian bilingual volume Le Trait qui nomme, on my ten years of dialogic creation and intense transmissions in the village of Koyo in Mali.

.

Poetry-painting installations with musicians in France

Concurrently, in France, I created the following works and, with a number of musicians, I was able to stage my very large format, original calligraphic poems:

La Soif , with fifteen calligraphies and clarinet, Paris, December 2013

Archipel Vigie , with eight calligraphies and saxophone, Die, September 2014; reprised in the Principality of Monaco in April 2015 with piano and violin;

Le cercle de pierres, with twelve calligraphies and saxophone, Die, August 2015.

Cheval-Proue , the first act of the long dramatic poem Carène, was first created in March 2016 with eight large calligraphies and violin at the Baptistery of Poitiers, March 2016; it had many repeat performances in France, in particular in Poissy, in June

2017, with four actors and four musicians; then with cello and a dancer at the Commanderie de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines in November 2019 and at the R. Manuel theater, in Plaisir in February 2020, etc.

These words-in-action poems always have several dimensions that go far beyond their book format. However, you can find the texts published on paper in L’Homme inadequat, Forme libere editions, Trento, 2012, and in Le Cercle de Pierres, editions Algra editore, Zafferana etnea, 2016. These two books also contain the texts of many poem-paintings that I created and calligraphed in the middle of the mountain on large quadriptych: their place of creation is always specified because they are acts of re-igniting a dialogue with the animist dimension of language-space of a given alpine mountain.

These books are bilingual, French-Italian.

Cheval-Proue is at the beginning of Carène : it is the first act.

Almost all the translations are the work of poet Francesco Marotta.

Quite a few elements of this work have been accessible on the blog “Carnet de la language-space”, since 2013.

Taking stock of the situation

Language-space, “landscape” and anthropology

Clearly, for the past twenty-five years, starting with my understanding generated by the red sheet metal barring the path to that squatted shack in Guadeloupe, language-space is not a typical European style, aesthetic or literary dimension of a place. The European dimension belongs to a set of educational, school, academic conventions relating to place, conventions that since Rousseau’s novels have developed the notion of “landscape”, an extremely fertile artefact, though narrowly local. Many Europeans, confined to their own culture, consider this notion of landscape to be “natural” and take it for granted.

Language-space is the complex social, historical, ritual sedimentation, primarily animistic in nature (before local deviations impose a transcendence in which a single invisible god is made to speak “behind or through the landscape ”). This sedimentation, as I had learned in the West Indies, is almost always a turbulent one, restless, it moves in jolts. Listening and trying to understand language-space requires a historical, sociological, anthropological approach: the truly extraordinary years I spent in Koyo have shown this to me every day. Europeans who are left with what they believe to be an “absolute” or a “universal” notion of “landscape” fail to understand that the word-in-action is created in the anthropological resonance of the place; to them “landscape” is merely a docile sounding board for their projective emotions and they refuse to accept the idea that colonialism first, then tourism, ended up exporting this landscape artefact everywhere. Of course, engaging in the work of this word-in-action does not require aspiring practitioners to be methodical researchers, but as Victor Segalen and Lorand Gaspar warned, they must be aware of the otherness of space: language-space is the choral speech of the other, past and present.

Every time I return to Europe, coming back from Koyo, I receive visits from ethnologists, anthropologists, ethno psychiatrists, curators with an open mind, art historians who are not obtuse, etc. They are deeply intrigued by the abundant transmissions that, without asking, eliciting and even less coercing, I have received with each creation in the desert mountain: all the more so because the process is almost the reverse of an “ethnographic survey” where one “asks an informant”, with the arrogant loftiness of European science, whose colonial prurience has not yet been removed.

Poetry and Anthropology

I then carefully reread Hesiod, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Marcel Detienne; equally carefully, I read the fascinating volumes of the collection L’Aube des peoples published by Gallimard: without ever letting out of my mind the six steps involved in the complex creation of a poem-painting, as I experienced in Koyo. It was becoming ever clearer to me that what has been called a poem by too many cultivated Europeans since Romanticism, though certainly refined when viewed within its own logic, is nothing but a local artefact clearly situated in a specific time and civilization.

This poem generally loses sight of its anthropological status within language-space and becomes constrained in a narrow ritual context made of lexicon and cliches, prizes, honors, academies and other various fine obsolete “rags” in which, luckily, hardly anyone is interested.

The sung word

During these past two decades, I have never stopped listening with great attention to recordings of non-European ethnomusicology, in particular those gathered in the Ocora / Radio-France collection. No, a poem written by a solitary individual, no matter how cursed or rebellious, is not universal. But what can be seen in all civilizations, and in particular when they are still within the borders of orality, is that there is always a specific verbal phenomenon of great density. This phenomenon unites and consolidates the community at specific times. It speaks in a specific entrancing, rhythmic way. It is often supported by an instrument that activates the dynamics of language-space. It speaks not to spectators but to participants and is in conversation with them; this verbal phenomenon has a strong ethical dimension. The sayer/cantor, whether woman or man, is an initiate, surrounded by the greatest respect of the community; s/he is never “cursed” or “misunderstood”. His or her “text oral-chant ”is memorized by the community; this text can sometimes be called an epic. The Italian language has not removed the word poema, whereas French academicism since Classicism has erased all adequate words and the phrase “dramatic poem” has become a bizarre and obscure one.

The image

Life in the mountains, on high mountains, in the desert and on volcanoes has always taught people to pay attention to their signs, however varied they may be. For three decades, the emergence of the graphic sign and what quickly becomes, a “feature that names”, has led me to observe signs and “features”, and then to analyze those who “place” them, to observe and analyze finally the arrangement of these signs and “features” in an image. Specifically, the way they are placed in a mural image, in societies that are still based in the oral. This image is performative and interacts effectively with its language-space. I have written numerous commentaries and articles on the subject; some can be found on the blog ” Carnet de la langue-espace“. Some in my French-Italian bilingual book L’Image en acte, Algra editore, Zafferana Atnea, 2017.

A new stage

In October 2016 the accidental and definitive loss of the use of my right ankle puts an end to my practice of poetry-in-space in the mountains.

February 2021: Now that a little over four decades have elapsed since publications, as you can gather from these “bio-bibliographical notes, I am in no way disowning (quite the contrary, actually), any of the poetry actions and installations nor the poems-in-space that I made over the years.

You could say that in Europe I have become stubborn; one could be totally pessimistic and say, in a very general way, that European language-space is increasingly and more pervasively ravaged or even shaped by the violence of populism and racism and by the appalling steamroller of global commodification. Well, I stand to be counted among those who never gives up seeking and opening breaches in this obscurantist stupidity: as René Char did in his most difficult of times.

And, to be exact, at the end of autumn 2016 my poems written as a form of rejection of infirmity have elicited-met the echo of the poems written by my main translator, Francesco Marotta: our creative dialogue never ceases and it will go as far as resulting in the “publication” of the book Aqua, in a few months.

And, to be exact, in the spring of 2020, at the time of the disquieting confinement under the pressure of the pandemic, I wrote the word-in-action, epic cycle La Maquette, in twelve episodes precisely as a way of rejecting any capitulation whatsoever. It is available on the blogs Carnet de la langue-espace and La Dimora del tempo sospeso: from the start I conceived this vast poema as a work with choir and soloists that will perhaps come out in a book format, but is primarily meant to be a complex theatrical action, Shakespearean in nature or even a movie.

The Dreaming Machine is deeply indebted to poet Gianluca Asmundo for introducing us to Yves Bergeret and helping in the English translation back and forth process with the author.