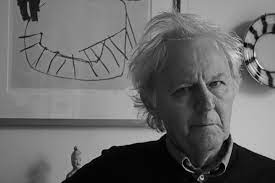

In memoriam of much missed poet, painter, critic and friend Fawzi Karim (1945 -2019) whose fourth death anniversary is this May. This article is republished courtesy of the author, Marius Kociejowski and Carcanet press; first publication in PNR 189, 2009. Greatly indebted to Lily Altai for providing the gallery of images of Fawzi Karim’s paintings and sketches, as well as arranging re-publication.

:

Greenford is not where one might expect to find one of Iraq’s most esteemed poets, and, in truth, I’d never quite registered the place. The likelihood of my going to Baghdad was just a bit less remote than of my ever finding reason to go to Greenford although I have been to Perivale. Young Poles have largely taken it over, such that ‘Greenfort’ is spoken of in Katowice, and even Gliwice, as a borough of promise. Although it sounds, and looks, like a modern suburb, it is first mentioned in a Saxon charter of AD 845 as ‘Grenan Forda’ and almost 200 years later it appears, verbally congealed, in the Domesday Book with a named population of twenty-seven people and one Frenchman. There were no Poles. An Iraqi was unthinkable. Another interesting thing about Greenford is that its tube station is the only one in London to have an escalator going from street level to platform level and it is also the last escalator to be made of wood. The others were replaced with steel in the wake of the King’s Cross fire. True to its name, Greenford boasts expanses of green across which I saw not a soul move.

Greenford, Middlesex. It slipped into one of John Betjeman’s verses.

I first met Fawzi Karim at a party in Kensington for a New York writer who is legendary for emptying the contents of other people’s refrigerators, as he did mine once. Also, when bored, which is often, he flings his hearing aid on the dinner table. The party, all in all, was not such a bad one. I was enthusiastically introduced to Fawzi by the poet Anthony Howell, co-translator of his long poem Plague Lands, which shall here serve as a template for his life. We spoke for ten minutes, maybe more, and although this was over a year ago, when it came time for me to seek out an Iraqi for my world journey through London it was Fawzi who first came to mind. Something about him had greatly struck me, which may have been the quietude of one in whom exquisite manners blots out the boorishness of barbaric times. (I might have said ‘civilised values’ but as of late the term has been hijacked by besuited savages.) And there was something, too, about Fawzi’s quiet, slightly gravelly, voice, which could be heard above the world’s noise. It was quite without pressure. Also, although this did not unduly influence me, he made kind remarks about a series of articles I’d written on Damascus, a city he knows well and which, on occasion, stands in for the city he is not able to return to.

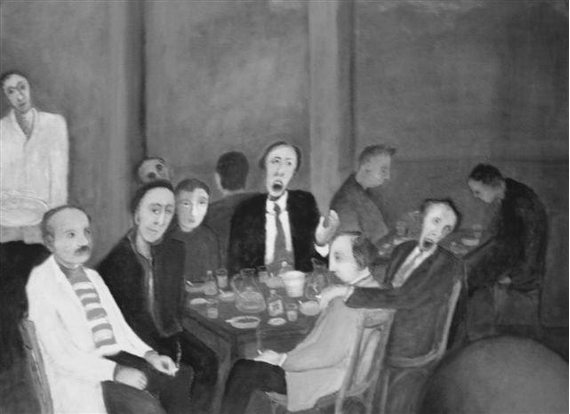

I arrived at his home in Greenford just as a Bach toccata was coming to a close. One wall of his living room is shelved with CDs of classical music, including almost every opera in existence. Fawzi, as I would soon discover, is one of the very few Arab authorities on western classical music. Also, there is an ancient wind-up HMV gramophone with a golden horn, similar to the one that was in his family home in Baghdad. Fawzi told me how, as a child, he listened endlessly to an old 78 of the Egyptian singer, Mohamed Abdel Wahab, and memorised the lyrics, repeating one line over and over, little realising he was duplicating a skip on the record’s surface. There are a good many books, many of them biographies of composers, and poetry, of course, in English and Arabic. And then there are the oil paintings that serve to demonstrate Fawzi might equally be considered an artist. But then, why not both? Why not get over this Anglo-Saxon prejudice of allowing people only a single vocation in life? The paintings are, in spirit and theme, perfectly aligned with his poems, and indeed Fawzi speaks of the paintings collectively as ‘a poet’s mirror’.

One canvas in particular haunts me.

The poet swims naked in the Tigris, the same age he was when he did the painting, in his late fifties. Fawzi, though, has not, at least in the physical universe, swum in those waters since his early teens. The image, even before one learns this, is dreamlike.

‘The sense I get is that the Tigris, even more so than the city it divides, is the great force behind your poetry. Correct me if I’m wrong, but it would appear it also flows through London.’

A serious man, Fawzi laughs only when he means to.

‘It may run even stronger here than at its source in Turkey because it belongs to memory rather than to reality which belongs to time that is completely gone. An important thing to remember about Iraq is that when dealing with memory and experience most people there belong to small, enclosed areas and not to the country as a whole. I grew up in Karkh area of Baghdad which is on the west side of the Tigris. My actual district was al-Abbasiyya, which is now completely gone. It was destroyed in order to make way for Saddam’s palace gardens. It was a beautiful area, natural and simple, full of palm trees. Many of its inhabitants were poor, their livelihood dependant on fishing, farming and dates. We would climb those palm trees, and the smell of the dates when they were not yet ripe, a stage that in Arabic is called tal‛a, was like human semen, a smell that still reminds me of growing into adulthood. The ancient Egyptians regarded the palm tree as a fertility symbol and from ancient times Iraqis have believed that palm trees contain souls. There is a famous book in our literature, an epistolary work by a group of tenth-century scholars and philosophers who called themselves Ikhwan al-Safa (“The Brethren of Purity”). To this day we do not know who they were, or who the compiler of their book was. Their encyclopaedia dealt with all aspects of existence, from the inanimate to plant life, to human, and the various stages in between. They spoke of the palm tree as being the last stage of plant life and first stage of human existence, which is why nobody would ever dream of cutting down one of those trees. There is even a legend of someone cutting into the crown of a palm and hearing a high-pitched voice coming from inside. Those trees are thought to have souls. During the war with Iran many hundreds of thousands of them were lost and then, in our area, Saddam cut them all down. There was an island in the middle of Tigris, which we’d cross over to in our boats. We would plant things there. We built temporary houses with hasir, which is made from reeds. The young people spent their nights there. I spent much of my childhood fishing and swimming in the river. Later, because it was too close to the palace, Saddam banned all boats and even swimming was forbidden. I had no experience of the river as a whole, only of the half kilometre or so which belonged to our area. At the same time, this water was a mythical thing that belonged to Sumerian civilisation. Myth cancels or diminishes the idea of time, so that you find yourself living in the same dimension as the Sumerians. That’s why in Plague Lands Gilgamesh and Enkidu are actually there.’

‘The Tigris will nudge us with its epics,’ writes Fawzi. Several pages into the poem, Gilgamesh appears beside the river in disguise. ‘What happened before will happen again,’ he says, to which the authorial voice in the poem replies, ‘Yes, but why the modern dress, Gilgamesh?’ Gilgamesh, looking over the embankment, sees corpses floating down the river, his own among them. Another image that appears early on in the poem relates to the ancient Iraqi custom of placing lit candles on plates made from rushes and floating them down the river in celebration of that most mysterious figure of religion and folklore, al-Khidr, a Muslim saint whose Christian and Jewish counterparts are St George and Elijah, and whose mythic origins may pre-date all three religions. It had been my intention once to pursue the subject of al-Khidr through the minds of the people who most revere him. It was a pleasant surprise to meet him again in Fawzi’s poem. As a figure who might serve to make all three religions tolerable to each other, there is none more appropriate.

‘I put a certain light on it now, of course, but I recognised that mythical dimension even at a very early age. Sometimes you understand things without language, as a kind of music inside you, which only much later becomes words. All that I have, even my relationship with the Book, has its origins in al-Abbasiyya. We had a Shi‛a mosque there called Hussainiyya, which I belonged to because of its library. As a young boy I became manager of that library. So I began there, with the Word and the Book, although not really with the information contained in those books, and even now I feel some separation between words and their meaning. I loved and collected books, often reading from them in my high voice. The Arabic books, especially the old ones, came mostly from Beirut and Cairo, and had uncut pages that one had to open with a knife. You could smell things rising from those pages. I could smell the shapes of words as they rose, and even their meanings had their own shapes. There was no separation, no paradox, between things. When later, insensitive to the religious atmosphere, I introduced volumes of modern poetry and prose, some of it quite irreligious, I was asked to leave.’

There is a paradox which remains at the very root of Fawzi’s thinking. One needs first to understand the layout of a typical Arabic home, the greater part of which is hidden from public view. Its rooms surround an open space, a small garden paradise suggestive of the greater Paradise that awaits those of high moral virtue.

‘When I was a child we had two trees in the courtyard of our house. There was the mulberry which was full of light, beneath whose spreading branches my aunt who was blind took shelter from the sun. I used to climb up between the leaves, and there the light flooded in from all directions. The other was the oleander which was the mulberry’s extreme opposite, a dim and closed tree, which never accepted our human presence. Its sap was bitter to the taste, sticky, and attracted flies. I like both these trees, but to which do I belong, the mulberry or the oleander? One is bright and open and extroverted, while the other absorbs the light and keeps it there. Although the worlds they represent are for me totally separate, I feel I belong to both of them. I think I prefer the first one, but it’s the second which pulls me more. When I speak about music and literature, the difference, say, between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, or Hemingway and Kafka, often I think of those two trees. Dostoevsky is the oleander because his dark journey is contained there. Among painters, the Expressionists belong to the oleander, unlike the Impressionists who belong to the mulberry, who go outside to play amid colour and light. When I listen to Brahms and Wagner, I am again reminded of my relationship with those trees. They are ideal models in a sense. They inhabit the same time period but are of wholly contradictory natures. Brahms is the autumn between two seasons, his love for Clara, though hidden, flashing like the light of the sun between the branches of the mulberry tree. Wagner, on the other hand, prefers the dark places of the soul. He is able to see there as do certain animals at night. His is a special light generated by darkness itself ― no need, for him, of sunlight. The love of Tristan and Isolde is a love of death too. Wagner is the perfect oleander. This is my struggle. I do not like the oleander ― nobody can like it ― so why am I obsessed by this dark, secretive tree, even though as a boy I belonged, body and soul, to the mulberry? Always there are these two directions between which I can’t choose. That’s why from the very beginning I felt it was impossible to believe, either religiously or ideologically, in any one thing. I am divided on the inside. While I may have been a Marxist once, in my early adulthood, as an ideology I knew Marxism was impossible. Marxism is a dream of thought and, like all dreams, is impossible to apply to real life. If you try to force theory onto real life what you get is a swamp of blood such as we had for much of the twentieth century. I can appreciate Plato’s Republic as a great work of imagination but to make this republic real would be to create a hell for people. I think my poems reflect this inner struggle or what the painter Kandinsky calls “the inner necessity”.’

We would salute that oleander, hot with our uniqueness.

That oleander of Fawzi’s childhood, whose shoots so often take root in his verse, was chopped down for firewood. This was when Saddam’s henchmen took over and destroyed people’s houses in order to make room for his palace. When Fawzi said the oleander’s sap was bitter to the taste, I wondered whose taste. The oleander contains toxic compounds, including cardiac glycosides, only a small dose of which can cause the heart to race and then dramatically slow down, often with fatal consequences. There is no part of the plant that does not contain a deadly poison, and its poisons are various. A single leaf can kill a child, and the bark contains rosagenin which produces effects not dissimilar to those caused by strychnine. The seeds may be ground up and, as has been the case in southern India, used for purposes of suicide. A small amount of sticky white sap causes the central nervous system to collapse, with resultant seizures and coma. What is especially poignant here is that its burning wood produces highly toxic fumes, which, as a symbol for a country in flames, could hardly be more apposite.

‘When I think back on my childhood on the Tigris, I realise there were all these great benefits. All the symbols became real, full of life and mythology. It is a river that continues to run through my poetry and which makes me realise that poetry does not deal directly with history but with myth. It is why I criticise most Arabic poets. A poet does not bow to the winds of history. The myth is generated from personal experience, from his struggle with history. The greater percentage of Arabic poetry pays lip service to this history, is like a mirror reflecting it, and too little comes from inner experience. These poets are believers, coming with their dogma, knowing well in advance what they want to say. Poetry, however, deals with something else. A poet has to neglect historical time and go beyond it ― he has to make his legend compared to which history is a mere shadow.’

Maybe what makes this image so arresting is its perspective. Fawzi, seven years old, stares not into ours but into his own distance. It’s as if everything in the photograph is set to his gaze. It is 1952, presumably winter ― well, cool enough for him to be wearing a coat ― and he is returning home from the school which, so I am told, is hidden somewhere in the shadows behind him. A smudge behind the vehicle, as if the ghost of some greyer architecture, is the old parliament building, which later was replaced by the National Assembly, and it will be on the road from there, six years hence, that Fawzi will see something terrible, which will direct the course of his life. The ditch filled with water ― there is another hidden from view on the opposite side of the road ― belongs to the ancient irrigation system that channels water directly from the Tigris to the gardens of the houses. Water is, for obvious reasons, a dominant theme in Arabic literature. (Worth noting is a famous hadith in which the Prophet Muhammad says one should never waste water even when sitting beside a river.) One of the buildings to our left of Fawzi is the local café. A bit deeper into the future, when Fawzi is seventeen and already plagued with verses, its owner will doubly, triply wipe the tea glasses clean, and, soon after, he would even break them because the lips that touched them were those of an Unbeliever, that is, if we are to equate a poet asking questions about existence with atheism.

What is even more interesting, and I mean no disrespect to our subject, is the ewe a few yards behind him. It belongs to a woman who lived in one of the houses nearby. The ewe is called Sakhlat al-Alawīyah which translates, somewhat clumsily, as ‘the sheep of the woman of the family of the Imam Ali’, and because it is so illustriously connected it is considered a sacred creature, which may go wherever it likes, whether it be into shops or houses, and almost always with a treat in store. Ill fortune comes to anyone careless enough to shoo it away. Fifty years later, a childhood friend of Fawzi’s, looking at this photograph, will remark, ‘Why, this is the ewe of the holy woman!’ There is nobody of that time and place who doesn’t know that creature. What the photo represents for Fawzi is not just a lost world but also, in the relationship between the ewe and the people among whom it so freely moves, forever safe from the butcher’s knife, a metaphysical one. It is a world in which a nearby tree, a Christ’s thorn, is believed to harbour a djinn that at night throws stones at people who come too close. It is a world of mystery and between it and its inhabitants there is an easy correspondence. Such questions as will be asked are the poet’s prerogative. The boy would already appear to know this. The ewe certainly does.

§

There are some people whose lives may be read as narratives, and others, Fawzi’s among them, whose lives can be seen as clusters of images. A Caesar demands a narrative; a Virgil is all images. We began with Fawzi swimming in the ancient waters of the Tigris. What is a river, though, without its bridge? A bridge is one of the most potent of images. It can symbolise a link between the perceptible and the imperceptible, a connection between direct opposites, or it can represent a transition from one world to another, or, with its destruction, a sundering between them. In 1952, when Fawzi was seven, his father worked on the construction of the nearby Queen Aliyah Bridge, which, after the Revolution of 1958, was renamed the Jumhuriyya Bridge or “The Bridge of the Republic”. There Fawzi would take his father picnics in the three-tiered container that has a Turkish rather than Arabic name: safartas. Fond though those memories are, they also contain an incident responsible for one of several violent passages in Fawzi’s poem, all the more terrifying for being presented in a flat conversational tone.

My father has been working on the bridge.

“Today a man fell,” he tells us.

“Landed in the pillar’s rod-mesh guts.

Didn’t have time to draw breath.

The mixer tipped and covered him quick

With the next load of cement.

A bridge has to have its sacrifice, I suppose.”

Those lines seem to connect to the construction, between 1931 and 1932, of the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal, when approximately 100,000 Gulag prisoners perished, their bodies used as fill by their Soviet masters who, much to Comrade Stalin’s pleasure, completed the work four months ahead of schedule.

‘This bridge became an important symbol in my writing. I was from a small, unknown area, and when, aged sixteen, I started publishing my first poems in magazines, nobody knew where I was from. There were no intellectuals in my area who could put me in the direction of poetry. I was the only person in my family who was a keen reader and painted and made sculptures. I grew up relatively isolated and my contact with books was with only the most traditional ones. I didn’t realise then how good this was for me. It was only later, aged nineteen or twenty, I went “across the river” to the Rusafa side and mixed with the Sixties generation. Crossing that bridge became symbolic for so much in my life. There, on the other side, each group had its own café. There was one café for Communists, another for Trotskyites, and yet another for Maoists and then there were still others for Ba‛thists, Pan-Arabists and so forth. One café was named after the singer, Om Khalsoum, and yet another was for blind people, many of whom played their instruments there. Those cafés were a very important part of our culture, but in some ways it was a dark scene. All the time I kept asking, “Where is my café? Where’s the café that represents my sense of perplexity and wonderment and separateness?” Everyone belonged to a political party or artistic direction. The writers who enthused about modernity behaved very much like ideologues, even to the extent of creating their own enemies. I could find no space between them. Those people of the 1960s with their readymade ideas remind me of the Russians of the 1860s. Dostoevsky wrote The Devils about them and so did Turgenev in his Fathers and Sons. Of course we didn’t have a Dostoevsky or Turgenev in our culture who could give voice to these matters. Our situation was similar to theirs in that we too had our devils, real ones, who with their crazy ideas sought to recreate the world on their level, who forced the people to think along similar lines, making them believe their problems could be resolved quickly through revolution. This is why Iraq was completely destroyed, and in the precisely the same way the Russian radicals of the 1860s were to blame so too were the Iraqi intellectuals of the 1960s.’

There comes in the poem a strange passage in which Fawzi and a friend are in a boat near the bridge when they witness some turbulence: ‘Yards away, some buckled chunk of shrapnel/smashes into the water’s face.’ It took me a couple of readings to determine where, chronologically, the reader is supposed to be. The temporal haze is deliberate. Although the scene is set in the early 1960s, the object the boys see arrives from thirty years or so in the future.

On January 17th, 1991, at the beginning of the operation known as Desert Storm, Major Joe Salata flew his sleek, bat-like F-117A Nighthawk, which the Saudis nickname Shabah or “Ghost”, through Baghdad’s night skies. At the dropping of those first bombs Salata made the utterance that was heard on news broadcasts all over the world and which reappears, slightly recast, in Fawzi’s poem: ‘The city lit up like a Christmas tree.’ Grossly inappropriate though the image may be, it was not the first time people have located beauty in destruction. Salata, speaking further of this event, says, ‘I can remember one target in Baghdad ― it was a bridge. My objective was to drop the bridge into the water. It wasn’t to kill everybody on the bridge, but I saw a car starting to drive across the bridge, and I actually aimed behind him, so he could pass over the bridge. If I had hit the left side of the bridge, he would’ve driven right into the explosion. Instead I hit the right side. You can pick and choose a little bit in the F-117 … I think the guy made it safely across the bridge, but you can’t really think about that when you’re at war. You could drive yourself crazy, thinking of those kind [sic] of things. If you have a target to hit, you hit it.’ Joe Salata, only two years Fawzi’s senior, made a perfect strike or what in military jargon is called ‘placing steel on target’. The column of the bridge, around which Fawzi used to swim, becomes, in the poem, the image of an uprooted tree.

It’s time to deepen

the gulf left by the roots

A tree uprooted grows tall.

Vacating its place of planting,

it grows, and then it vanishes

Like smoke:

On the water’s face

nothing but the shiver of a breeze.

My friend and I are in a boat.

We lean over and lift the shiver

Off the face of the water,

making a net of our hands.

The fish quiver, leap and vanish.

The bombing of that bridge was something Fawzi watched on television, in Greenford, and now, at a curious point in our history, where communication is both remote and intimate, a quick search on the internet reveals the name of he who fired the missile.

§

On July 14th, 1958, when Fawzi was thirteen, General ‛Abd al-Karim Qasim marched into Baghdad and within hours effectively put an end to Iraq’s Hashemite Dynasty. The coup, which was welcomed by the majority of people, was one of the most savage in recent Arab history. The young King Faisal and twenty members of his family, including women and children, were butchered. The evening before, when the world seemed at peace, a Pakistani magician had put on a show for the children, among the entertainments a couple of trained turtle-doves, one of which pulled the other in a small cart. They flapped their wings and picked up small objects when told to. Where did those doves go? There is an Arabic term sahel, which means to humiliate a person by dragging his corpse through the street. Sahel was the Iraqi Revolution’s guillotine. It became symbolic of what happens when a people temporarily, and collectively, goes insane. The corpse of the Crown Prince, ‛Abd al-Ilah ― ‘hound of the imperialists’, according to slogans of the time ― after being cleaved of its hands and feet, was then mutilated and dragged over the Aliyah Bridge to the gate of the Ministry of Defence where it was hanged. After the souvenir hunters had their way with it, there remained only a piece of backbone. Prime Minister Nuri al-Said (‘lackey of the West’), who once rode with T.E. Lawrence, attempted to make his escape dressed as a woman but was spotted when the bottoms of his pyjamas showed beneath the aba or black gown. There is still debate as to whether he was shot or committed suicide.

‘It is very hard to speak of this because I did not fully understand what was going on. I was very young. They took Nuri’s corpse, burnt it, dismembered it, dragged the pieces all over the streets of Baghdad for three days, and after that they hung them from the bridge. The burning thigh I saw with my own eyes, close to my house. All of us ran after it and started shouting revolutionary slogans but I returned home quickly because of the smell of the burning flesh. You can’t imagine from where such hatred comes.’

We saw the world with its trousers down and laughed.

We opened vents for the smell in our shackled bodies

And the smell disappeared within us.

That revolutionary summer had just such a smell.

And my father said, “Whoever goes sniffing out corpses

would want to be rid of their stench.”

‘And because I actually saw this, it came naturally into my poem although there, of course, it takes on a different hue, one that suits the imagination of someone like me. Most of what we have seen since in Iraq is a variation of what happened in the course of that single day. This event produced a great crisis in my unconscious.’

‘You spoke earlier of having crossed the bridge to the Sixties, yet you remain critical of them.’

‘What happened with my generation happened everywhere. This is why I criticise the Sixties altogether, whether they were in America or Paris or Iraq. That generation didn’t look to the earth but rather to their own thoughts which seemed so bright at the time.’

‘Surely, though, the Sixties in Iraq must have been very different.’

‘Completely, but it tried to copy the Sixties in the West. I am speaking of the intellectuals, of course. They were dreamers full of hate, whose great ideas went ultimately against humanity.’

‘You speak of modern Arabic poetry as not being able to embrace the truth and as having become a vehicle for hate.’

‘The ideological mind has a clear way. It knows where it ends. The dogmatic person sees clearly the future, which is why he urges people to look there and to neglect the past and present altogether. That’s why our countries prefer anthems that sing of the future. This mind in order to give meaning to the struggle must create an enemy especially if there isn’t one already there. It got so every idea in our society was a political one. You had to be Communist or Ba‛thist or, in later years, Islamicist. If poetry does not have the capacity to build a party with guns and knives, then at least it can manipulate the emotions to inspire hatred. One of our best poets, ‛Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayyati, wrote a line, “We will make ashtrays out of their skulls.” Another poet wrote, “I made from the skin of my enemies a tent to shield myself from the sun” and yet another warns that when he gets hungry he will eat the flesh of his enemy. These may be strong images, but really they are the opposite of strength. They have nothing to do with real poetry.’

‘Clearly you are outside the mainstream of modern Arabic poetry. When did that separation begin?’

‘I think it was there from the start. My first collection of poems, Where Things Begin, published in 1968, when I was twenty-four, did not speak of anything ordinarily dealt with at the time. Those poems as a whole were a kind of song without words and as such constitute a brief romantic period in my creative life. The separation was already there, not because of the intellectual atmosphere or the life I was leading but because of something in my own nature. Even the book’s title points to a profound difference between me and my generation. When I think back on the titles of other collections published at that time ― Ashes of Bereavement, for example, or Dead on the Waiting List or Silence Does Not Bother the Dead ― they may sound nice in Arabic but they are empty of meaning. What is reflected in them is the disappointment that hit at their authors’ dreams of changing the world through “great ideas”. The revolutionary parties to which they belonged failed them although even then they didn’t learn. I preferred to start with the things in life and nature that surrounded me, which were close to the earth.’

‘You had a great mentor at that time.’

‘Yes, the Iraqi poet, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab. I had been looking for new things, especially those coming from Europe via Beirut. Adonis was an important poet for me, but his brightness and greatness belonged not to my own experience but to Modernism. There is nothing from his inner experience, nothing unique. That is what I want from a poem. What I realise now is that the “newness” I was after had another name: timelessness. I get the “new” only when I start digging into the past. When one is young it is a beautiful thing to think about the world and to interpret it in a different way, but with experience the poet looks behind the surface, conversing with what is hidden there. Likewise, he writes his poem for the hidden reader. I am not modern. When finally I realised this, I went back to al-Sayyab. When I was young I would sit with my friends, most of whom were not writers, by the Tigris singing his poems, and even now I sing them. A great poet is one who can make dialogue with me. A poet with whom I am unable to do this is not my poet. Al-Sayyab became a Communist but later the Communists hurt him deeply and so he became a Pan-Arabist but, really, he didn’t believe in either. He believed, rather, in his own weakness, his isolation among poets who thought of themselves as prophets. He died in 1964, aged thirty-eight, destroyed by everything ― the politics, the intellectuals, the women, none of whom loved him although now some of them write memoirs about their warm relationship with him. He was someone who could elevate history with mythology such that even his village, Jaykour, has become a mythical place. If you mention Jaykour in Syria, they will say “The village of al-Sayyab.” But it is not the Jaykour of real life. If you mention the Buwayb River everyone will tell you this is the river that runs through al-Sayyab’s poetry, but if you go to Basra you’ll find it is only a tiny stream. This river became for him a mythical thing, a part of his underground world which he could belong to rather than to this world.’

‘You say the intellectuals were largely responsible for the country’s demise.’

‘We did not have journalists as such at that time. They were mostly intellectuals ― poets, writers, or critics. They were the only ones who stood between culture and the people, between ideas and the people. Such ideas as ordinary people had were all taken from the media ― TV, radio and newspapers ― or else from the political parties, all of which were run by intellectuals. When I describe the café scene as terrible, it is because there were no people there, only ideas. There were answers but never any questions in those places and yet each coterie had its own answer as to what the truth is. I will give you an illustration. I had a good friend, a typical Communist writer, a very nice man whose ideas were so clearly put they didn’t allow for questions. This friend was born in the al-Shawaka area of Baghdad. Baghdad has many districts which are either Sunni or Shi‛a. So here we have al-Shawaka which is Shi‛a and al-Joiafir which is Sunni and separating them is a narrow street, al-Shuhada, which has a lot of doctors and pharmacies. When life was relaxed there was no difficulty between those two sides. When the ideological crisis came, al-Shawaka became Communist and al-Joiafir became Pan-Arabist. The first preferred tomatoes because they are red, Communism’s colour, and the second preferred cucumbers because they are green, the colour of the Pan-Arabist movement. I said to my friend, “Try to use your imagination. Suppose you were born fifteen metres away from here, just across the road, what do you think you would have become? You would have been a pan-Arabist, not a Communist! You are seventy now and you have clung to this illusion simply because, satisfied with readymade answers, you want to be free of having to ask questions. Yet so many people were killed for this illusion.’

‘This brings us to the subject of your first escape from Iraq.’

‘When the Ba‛thists came to power in 1968, I went to Beirut. At that time I left my job as a teacher of Arabic, which I had greatly enjoyed. A lot of boys became good readers simply because I was with them for those nine months. The secret police came to my school, asking questions about me. At that time the Ba‛thists began to focus on teachers, and because I was neither Communist nor Ba‛thist I was more suspect. If I were taken into custody, there would have been no party behind me. I was accused of stepping outside my lessons and of talking to my students about literature. This was my style of teaching. I talked about Arabic writers and because my students lived far from the centre of Baghdad, I brought them books. A number of students whose families were Ba‛thist informed on me. They said I spoke about the devil or the angel and that I had caused them to stray from their studies or that I had advised them to read certain writers. They accused me of being a liberal ― librale ― which was very dangerous accusation because to be liberal meant that one belonged not to any single ideology, Ba‛thism or Communism, but to the West. Luckily for me, a relative of mine was then head of the Department of Education and had all the records on me. He warned me to take care, saying information was being gathered on me. So I went to Beirut. My family knew nothing about it. I was twenty-four at the time. I had already published my first book in Baghdad and so I was known in Beirut. Also I was published there in Sh‛ir and al-Adab magazines. At first Beirut was a paradise. It was like Paris. There I read Sartre, Camus and Eliot although I didn’t really know how to be modern. I went deeply into things that were never really part of my inner life. It was like watching a lovely American film in darkness and then stepping out into the light and seeing life as it really was. I stayed in Beirut for two and a half years. The poet Yusuf al-Khal was there. Adonis helped me. But a lot of things in Beirut began to destroy me. I started to drink. Alcohol was cheap. Then, in 1971-2, in Iraq, there was a coalition between the Ba‛thists and Communists. There was a sense of relief and that maybe now things would get better. So I returned there.’

The story of that return provides what in the poem feels like a sweet hell of dissolution of endless booze, of evenings spent in debate at the Gardenia Tavern, now long gone, which in Fawzi’s writings has become a kind of spiritual home, and of sleeping rough on park benches.

The waiter sees the mud on my galoshes

And sweat, from a wank, on my brow.

A reek, as from the underwings of bats,

wafts out, freed from my armpits.

The waiter tries to head me off.

Ah, but the summer urges me

To trample fields not trampled on before

Or take the shape of a beast from another time.

The irony is that for Fawzi and others of his generation it was a kind of blighted paradise, a hallucinogenic lull before all hell broke loose.

‘Yes, but it wasn’t such a hell really. Compared to what would follow, it was rather beautiful at that time. We had a safe, if brief, existence. After we left the taverns the best thing was to sleep outside beside the river. This was normal. That was a good period in our history. After the British companies left, the money from the oil was all ours. The Ba‛thists showed another face, although at that time I knew Saddam, this man who when he was sixteen killed his own cousin, to be a filthy man. The Communists had to defend him, saying this was our man. Only a couple of years later, Saddam’s black cars, eight of them, without licence plates, with black curtains in the windows, became a symbol of terror. They drove everywhere at high speed, and from any one of those cars men would leap out and grab somebody, taking him God knows where. If anyone went near one of those cars, he would be arrested. People had no idea if Saddam was in any of them or not. Saddam’s name became more important and terrifying than the President’s. I knew this man would be the realisation of all my darkest fears.’

‘You must have witnessed many tragedies, writers who thought they could embrace one ideology or another and were subsequently destroyed by those choices.’

‘They paid no attention to the idea of truth, even if there wasn’t any truth to be found, or to the idea of asking questions even if there were no answers. I broke with a couple of friends when they joined the Ba‛thists. On the other hand I had many Ba‛thist friends, a couple of whom protected me several times, but they were mostly people who were in it from the beginning and not like those who later became Ba‛thist just so they could have money and power. These people I avoided. The Revolution destroyed people. People were murdered or else killed themselves.

My generation’s had to put up

With its fair share of knocks.

One hid his head inside a shell

And lived below the surface for a while;

Another died within his coat as he tore at his insides

In a country where brigades of fans

Just blow away the dunes.

There is nothing I can say about the people I knew that wouldn’t apply to the many thousands of others who died. Actually, most of my friends died of other causes, drink, for example. I dedicated my Collected Poems to twelve people, some of whom were killed, others who simply died young, but I say all of them were killed. They were victims.’

One poet Fawzi remembers in particular is ‛Abdul-Amir al-Husairi whom he describes as ‘the hero of his own dream’. This poète maudit has come to represent for Fawzi and for others of his generation the dying gasp of a romanticism that may owe more to the bottle than to verse. Al-Husairi came from Najaf which is one of the centres of religious learning, home to the Imam ‛Ali Mosque, whose resplendent dome is made of 7,777 golden tiles, and which for Shi‛a is the third holiest shrine in existence. For a young poet deeply rooted in classical Arabic literature, the move, in 1959, from such a pious atmosphere to Baghdad, now capital of revolution, was a traumatic one. In a new world that demanded of every intellectual that he be aglow with ideological passion, al-Husairi, oblivious to the political circus, saw only that life was increasingly getting worse for most people.

‘A very talented poet, he was surrounded by some of the best writers of the time. A romantic, which is how I see myself, that is, belonging to a struggle that involves the duality between freedom and necessity, individuality and responsibility, al-Husairi was, symbolically speaking, the last of his kind. We all drank, of course. Alcohol was an important dimension of any poet at that time. If al-Husairi drank more heavily than us, it was probably because he didn’t belong to anything and so, in his alienation, drank all the more. A man of dreams, he was in despair, and finally the drink swallowed him. He lived in a cheap hotel in al-Maidan and every morning he would begin his journey from there, across Baghdad, to Abu Nuwas Street where our Gardenia Tavern was. You need at least an hour and a half, walking in a straight line, to get from where he was to where we were. It took much longer, of course, because he stopped at every bar on the way. Everybody in those bars knew and accepted him. “Here comes al-Husairi!” they’d say and so he would sit with them, drinking one or two glasses of arak before moving on, and so, stopping at each place, he would finally come to us at the Gardenia. He would settle there for a while, very proud inside his dream, and spoke like a god, and this we accepted although we wouldn’t have done so from anyone else. Then he would continue the rest of his journey by the end of which he would have consumed roughly two litres of arak. We all knew that one day soon we would hear of his death. When it came, in 1973, he was still a young man. The great thing about this character was that everybody, even the ordinary people on the street, knew him. This popularity was of a kind that has completely vanished from Baghdadi existence. Al-Husairi was the last glimpse of a great period now gone forever. He was the scion of a great village called Iraq. I did a drawing of him naked.

‘With regard to this recurring image of nakedness in my work, I did a large painting once, of an imaginary festival in Baghdad, which depicts a brass band playing, people dancing, people preparing food as if for a special occasion, and in it everybody is naked. Why naked? The naked ones are the dead coming back to life and what you have in the painting is a whole city putting on this great festival in order to receive them. When I drew al-Husairi naked, I believe I did so unconsciously. This is how the image came to me: he was naked because he was dead. When I make drawings of al-Sayyab, I also do him naked. So nakedness for me is an image of something coming from another world, from death itself. I even did a painting of myself naked in a room, with a bottle of wine.’

‘And then, of course, there were those who went the other way.’

‘You need to be a very sensitive and talented in order to feel deeply about this tragedy. Most people weren’t. Others simply became bad people. I do not wish to mention them by name. Still others tried to get on as best as possible. I will give you another example. One of my friends is a good short story writer who writes about the inner struggles of people, or about the struggles between them and their fate, or about their condition, which is that of always looking for the light. One of his stories is about a man seeking death because for him the height of desire is to vanish. We had all these voices, saying life’s problems could be resolved through ideas and ideologies, and then along comes this writer who speaks about things which are so deep. This is what writing should do, teach us how to live. Anyway, it was impossible for such a man to involve himself with politics. At that time Saddam started to support writers, often giving them expensive gifts or money. Saddam sent my friend a Mercedes-Benz. A car in Baghdad is very expensive to run and the Mercedes-Benz was worth more than his house. This was a gift from Saddam, so what could he do? He couldn’t refuse this gift coming from someone so terrible. Also he couldn’t drive. He couldn’t give the car to anyone else to drive nor could he sell it because if the secret police found out he’d be in trouble. So he moved the car inside his house and from then on he spent much of his time on it, cleaning it every two or three days because it was not good to leave the engine. He did this for a couple of years and, after a while, when the tyres started to sag from disuse, he propped the car up on stones. All this was just so he could avoid problems. Chekhov could have written a story about this nightmare. It is such a dark and beautiful theme, what the Russians call “a smile between tears”, and all this poor man could do was grimace.’

§

Fawzi, it has to be said, is a good cook. It must have taken him ages to stuff the tomatoes, peppers and courgettes with herb-infused meat and rice, a Baghdadi specialty. Our move to the dinner table, in a room flooded with light, where a wasp flew in circles, also provided a natural turning point in our conservation, which now focused on his decision to leave Baghdad forever.

‘I did so because I wanted to survive. I desired another language, true, but this was not the main thing that drove me out. It was in order to survive. When I returned from Beirut I wrote for a weekly magazine. I received a fixed wage, although I was not formally employed, either as a worker or a journalist. I preferred this. If I wanted to leave the country, however, I had to get written permission from my head of department, which I couldn’t do because I wasn’t working officially. So I persuaded a Ba‛thist friend to ask the director who, by the way, was a well-known poet, to give me this paper granting me leave to travel for two weeks. My friend tried several times and each time was refused, the director’s excuse being that once I was on the outside I’d write a poem against the regime. He said this even though he knew I wasn’t a political writer! One day, without realising it, he signed the paper. It was the end of the day, and he wanted to go home, and so, without looking at them, he hurriedly signed all the papers in front of him. The following morning a nice old man who brought us tea said, “Fawzi, this is for you.” I told my friend, and he said, “Don’t tell anyone!” I got my passport in a couple of days.’

My friend, take off your shoes.

Take off your shoes and go barefoot,

For this is the last time we tread

The ground of our country.

Tomorrow the footwear of exile will fit us both.

‘First I went to Paris which is “the city of light”, where everything’s on the outside. Paris, the Latin Quarter in particular, is traditionally the first choice of Arab intellectuals. I stayed there for a month. I can’t criticise Paris which, after all, is the heart of Europe. I had come from Baghdad, which was very poor and simple, to the great city of Sartre, Camus, Rimbaud and Mallarmé. But I didn’t really like it there. The French are so very fashionable, changing all the time, and with the Arabs it’s the same. Every couple of years or so, we have a new school of thinking. I hate all that. My time does not move. In Arabic we call it dhar or, in English, “eternal time”. When I came to Dover the policeman asked me, “Why are you visiting Britain?” I didn’t have the English words with which to answer him. “Holiday?” he asked. Still I couldn’t understand, so I started looking for a small dictionary I’d brought with me. I couldn’t find it. “Okay, okay,” he said, “You’re on holiday,” and let me pass. It was like a dream. When I arrived at Victoria Station, I knew immediately this was my city. I felt something here embrace me. I had left a country where I spent five years in darkness, which was not safe, where anything could happen to you. I was frightened, of course. Again I go back to those two trees. Paris is the mulberry tree, full of light, all my friends sitting and chatting in the cafés, while London is the oleander where everything is wet and dark or else hidden behind walls. When I begin to compare them, I can see why I love London more. It’s because it brings me to myself, to what is deep inside me, and to what I need. Here was a country which had Romanticism for two hundred years and also there were the same red double-decker buses that we had in Baghdad. I worked as a proof-reader for an Arabic newspaper. I didn’t work as a journalist, which was a good thing because I didn’t have to mix my poetic with journalistic language. I started writing articles on music. I got a bicycle. I had one in Baghdad. It was not often you saw a poet on a bicycle there. They called me “Abu Bicycle”. With time, I came to love London in a real way and also, of course, the English language. London is a very generous city. If I belong to any city, it is this one. I appreciate its humanistic side even though, in 1981, I was attacked and badly beaten by skinheads in Earls Court. I was on the way home from seeing Rigoletto, carrying my bright red programme. There are bad people everywhere. This city gave me, for the first time in my life, a place to live. In Baghdad I lived in cheap hotels, seedy rooms in poor areas. And then, in the first year I was here, I had a serious heart attack. My friends said, “You fled Iraq only for this to happen?” I lost all hope. I felt this was the end of life. Strangely, though, this awful experience greatly benefited me. Maybe it gave me more than life itself gave me. Death had come so simply. The word became real, maybe deeper than reality itself. All of us speak about death, but really it’s only words. What is the difference between words and experience? You may have a lot of things but not the fruit that comes from them. A great man may know death without experiencing it ― he does not need to be on a deathbed to understand that without death life is nothing and that it can push the poet or thinker onto a road of knowledge and wisdom that previously had seemed inaccessible.’

‘You say you have not been able to swim in English time.’

‘Sometimes I feel I am not really living here and that for these past thirty years I have been inside a great library. I go to the shelves, remove a book, and then replace it. I may enjoy this, but it is not really life. I think that in order to feel he is alive a writer needs to know that somebody somewhere is talking to him. A reader who likes what I write speaks with me. Maybe this is what I have lost or what I miss most living here. I am not English. I do not live among English people. I do not have English friends. I met some English poets, but with them it was mainly sitting and talking arbitrarily about things on the outside, nothing ever really in depth, and then nobody contacts you afterwards. Still I don’t feel I’m so terribly isolated because my close friends are books and music. I need at least double this life to obtain half of what I want. This isolation is not life, however, and maybe to say I am living in a great library sounds a shade dramatic. Sometimes, though, I feel I am waiting, like Godot, at a train stop. A train comes every minute, full of people, and there is no space for me. So it is very hard to speak about this and to which time I belong when I don’t belong to any. Maybe this is the tragic side of my life or, because I feel it so deeply, it might even be the most enjoyable side. The richest part of my intellectual life has been spent here. Modern English poetry is still hard for me, and much of what I see is, I think, very provincial. You need to be a Londoner to understand a London poet. I am involved with a metaphysical dimension, which is why I prefer poets like Czesław Miłosz who are similarly engaged. Only there, in that dimension, do I find someone to speak to.’

‘When you first came here, did it take a while to find your poetic voice again?’

‘I think I stayed silent for just one or two years, but then I busied myself with a lot of other things. I studied language, and I tried to read English books. When you first came here from Canada it was, in a sense, like going from one village to another, both of which had similar cultures, the same poets and the same philosophers, but coming from a place like Baghdad meant I had to cross a much deeper divide. And now my friends are dead or else they have become old and the places I knew are gone, the Gardenia Tavern, for example.’

The Gardenia belongs to Fawzi’s massive store of images. When he returned to Baghdad for the first time, in 2004, he found it closed and it has become yet another place which he can revisit only in painting and verse. It is the subject of one of his most powerful canvases. The empty space at the lower right-hand corner is where the poet al-Husairi should be.

‘When I say my time is gone, I speak as a poet. It is not difficult for me to go to Damascus and to re-enter Arabic time, which means just happily sitting there and watching, and thinking about nothing at all, and going towards nowhere in particular. I need this sometimes, but I couldn’t live there. Anyway, as you said to me earlier, Arabic Time is disappearing ― it is being replaced by World Time.’

‘Away from your audience, what enables you, or pushes you, to write? Who are you writing for?’

‘Sometimes I feel I write for nobody at all but at least in some corner of this world, and I have experienced this several times, there are people who read my poems and like them and feel they have a dialogue with them.’

‘So maybe being here has helped you.’

‘It has helped me a lot! If we both understand what we mean by the word “exile”, I am not an exile in the way many people like to think. I’d sooner say I was already an exile in Iraq when I began to write. I felt language to be an obstacle, and not a thing I needed, and that it was impossible to push language all the way to its roots. Often I tell people if I could be anything else it would be a composer and this is because music is abstract and as such it is where my passion and my struggles lie. Words alone just won’t do it for me. When dealing with language, a poet has certain problems because the words he uses are the words everybody else uses. We know language is the only tool of communication between people. So I come to words, wishing to use them in a completely different way, but will the language go easily with me? Will she accept me as a visitor and allow me to use her differently from, say, how a scientist does? The important point here is that rather than settle for the language we all use, I dream of going back to its very roots, to the very origins of language. When a human begins to give expression to something he starts with movement ― words come later. At the beginning there was no gap between the word and the thing it describes. With time, that gap became bigger and bigger and the words became symbols for many other things as well. So when a poet deals with language, he dreams about returning to its source, when the word was the thing, but already he is an exile because there is a gap between the thing said and what he desires. He struggles to close this gap, but it is impossible. This is the first dimension of exile. If we go to another dimension, another level of exile, here you are, someone who thinks and feels and sees differently from the people around you. This is the problem between the individual as poet and his society. It’s not easy really. When I was quite young I dropped everything and went to Beirut. Most of my dreams at that time contained my mother and father because I hadn’t yet finished with them, I still needed them, but I needed to leave too. So this, in addition to the other two I have just described, was another form of exile. When I returned to Baghdad, I knew something was forcing me. It wasn’t really a matter of choice. It was partly the illusion that everything there was about to improve, the political coalition being a new step towards paradise, but I knew this to be foolish. Also, I needed to return because I was tired of Beirut and of being without work or money. All the while I knew it would be going back to hell and so, for another six or seven years, I struggled inside this hell. The other day I wrote a poem in which time becomes a boat on the Tigris and it goes with the current to the sea and there vanishes completely. So I came to London. I watch the Thames here, full of boats and with no space for any smaller ones between them. It is not my time at all. That’s why I say it is not so bad to live without time. And this is what I mean about exile inside language, that there is some great source which is forever lost. We are exiled from the origins of language. So it’s not really true when I say I have written a new poem. There is no new poem. One just repeats things, adding a little bit here and there to the great store of poetry that has been available since Gilgamesh. If the “new” happens, it does so only on the surface or with technical matters. For thirty years now, I have had this familiarity with English or Western poetry ― I do not differentiate between England and the rest of Europe because for me the West is one huge country. If I have familiarised myself with Western art and poetry and philosophy and music, and I’m still pursuing things as yet unknown to me, I have failed to do the same with people themselves. I think this is not only a very deep exile but also a tragedy. And ― this is the terrible thing ― I enjoy it! If I could choose, if I could be familiar with the people who love their culture, it would be great thing, but it seems impossible now, especially at my age. This is hard for me and yet this gives me depth and courage. I do not feel I am dealing with ordinary things but with the exceptional. So it is not necessarily a negative exile. When I think about exile, it is not in the ordinary sense of the word. It is one of many dimensions. I remember once looking at a map of the universe, with its millions of galaxies, surrounded by this great darkness from which it is impossible to derive any answers, and I felt there was no space for our galaxy with its sun and earth and of course there was no space for me. This gave me a deep sense of universal exile. Suddenly I felt this great loneliness and a sense of no longer being safe. It was as if I were a child seeing his house for the first time without his father and mother. This sense of not belonging anywhere is what provided me with the first glimpse of a metaphysical dimension.’

‘And being surrounded by the English language, has that in some way helped purify your Arabic?’

‘Yes, the English language has greatly benefited me, not just with the logical structure of its sentences but also, most importantly, with its sense of justice. In Arabic, there are many words which I’d call “unjust”. For example, often when we speak about something or someone we’ll automatically add ‛alā al-itlāq, which means “absolutely”. We use this word all the time and yet it doesn’t allow space for either the speaker or the listener to understand his limitations. Arabic puts great value on the sound of the voice, the tone of the rhetoric. What is said in Arabic is so abstract, so boundless, whereas in English you don’t employ more words than you require. This has affected my poetry, which is why when I return to my old poems I see in them a lot of meaningless space. The great classical eighth-century writer, Al-Jāhiz, said that one shouldn’t care too much about the meaning, that meaning can be got anywhere on the streets, whereas what is more important are the shapes and sounds of words. Our critics repeat this still. I will give you another, perhaps more direct, example. We have Arabic states led by dictators everywhere, from Morocco to Iraq. I am talking about the last hundred years. We have no democratic states. These dictators stand and speak to the people and even if what they say sounds nice you feel some sort of command in their talk. This has been reflected in our literature. When we write, we do not think about the listener or reader as being another part of the conversation. This takes from the very soul of writing itself. It is undemocratic. We are excluding our audience from the dialogue. When I write a poem I want to feel somebody somewhere listens to me and converses with me, thereby giving life to the poem. This is almost a dead issue in our modern literature. I already gave you a couple of examples of strong images, which to my mind merely denote hate. This is something terrible we have in our language. The poet says what he does not really mean, which has nothing to do with his experience, and which he himself does not believe. It is not necessary for him to believe in what he says but rather to present a strong image. That is why even our great classical poet al-Mutanabbi is full of these lies. They may be powerful images, but I read them as expressions of strong hate. This is what I mean by justice. As a consequence of being here, I have become very close to the idea of the simple sentence, one in which there is no exaggerated feeling or idea or belief. It is better to leave things just as they are. Once you add these other things you misjudge, you become unjust. The Arabic poetry of the last forty years has become so empty, such that with many books you can’t even get past their titles. You then go inside them and there is no solid basis of knowledge, no dialogue with surrounding experience, nothing there is settled, and yet the language stays afloat like a balloon, growing inside itself. There is no weight of human experience. This covers almost seventy per cent of Arabic writing in that it is artificial and empty. You have these post-modernists imitating New York, and even now, in these terrible times, they are speaking in the same tone. This is the height of carelessness. It is not necessary for Baghdad to become Paris in order that good poetry being written there. This is the story of my struggle with Arab intellectuals, which is why most of my books do not go down well with them.’

We barely quarried the mountain of food Fawzi made. There was enough to see him through for a week or so. We moved back into the relative darkness of his living room where I suggested we end where we began, with the painting of him swimming in the Tigris, which depicts him as an older man rather than the child he was when he last swam there.

‘Painting for me is a relaxation from writing poems. Writing makes me tense, whereas painting is like going for a walk in wide open spaces. It is a working of the soul and body together. Some friends of mine who are painters say this is not painting in the way they understand it because usually one starts from colours, shapes and lines. They say I know how it will end in advance. This is not strictly true, but always the image is the first thing to come to me. I remember that the sense I had while painting this was of a man dreaming he is still swimming in the Tigris. As I said before, I do not live as others do, inside a current of ordinary time. You can see in the upper corner of the painting a wooden boat, called belem in the local dialect, which at that time was a principal means of river transport. Those boats are no longer in existence. Saddam forbade their use. The secret police destroyed my brother’s boat and then beat him. The water in this painting has a double nature. It reflects a richness of life which at the same time is horrible. It is like the Will of Schopenhauer, a blind force that gives life and death at the same time. When you read Sumerian literature, the water there has another life. In the marshes in the south of Iraq, where the Tigris and the Euphrates meet, you get this still water, the stillness making it seem all that much darker. The ancient Sumerians believed it was at that place one crossed over to another world. It was where, each year, the god Thammuz began his great voyage to the underworld. Al-Sayyab felt instinctively that this water was a current of hidden time. It is pretty much the same with the water in my poetry. I call these paintings “the poet’s mirror”. Sometimes what he sees is devilish in nature, a madman with a dark figure behind him or a naked man sitting in a strange, empty room with his bottle of wine. I think you can deal with these paintings in the same way you deal with my poems.’

‘Would you ever go back to Iraq to live?’

‘I don’t think so. Even if everything settles down in Iraq, and I go back there to live, I’d swim in a time that has nothing to do with me any more. Simultaneously this encourages me. It gives my poetry a new dimension. The idea that my time is dead is not really such a bad one. I have not swum in English time either. A friend of mine, a good writer, tells me this is wrong, that I must belong to what I have now. “You should write in English,” he tells me. Maybe he is right, but even if that were possible I don’t think I could give in English what I can still give in Arabic. The fact that I can give at all is because I am in a void. This is no bad thing. Most people need time. A poet doesn’t need time.’

Always the gentleman, and also because a dicky heart requires he take exercise, Fawzi put on his cream summer blazer which, maybe because of his dark complexion, makes him look so handsome, and accompanied me to Greenford Station where, uniquely for London, although commonplace for those who live there, one goes up to the train platform on a wooden escalator which has been granted, to the joy of rail enthusiasts everywhere, a stay of execution. This, too, was a journey outside time.

Marius Kociejowski is a poet, essayist and travel writer. He is the author of several books, including The Street Philosopher and the Holy Fool: A Syrian Journey and The Pigeon Wars of Damascus.