Introduction

In June 2017, the Italian publisher minimum fax released Sarà un capolavoro: lettere all’agente, all’editor e agli amici scrittori by F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Leonardo G. Luccone and translated by Vincenzo Perna. This publication shows that the interest for the American writer in Italy has finally reached a critical turning point that we have been waiting for a long time. This latest translation, in fact, is neither a novel nor a collection of short stories, but a sorely needed guide to the private landscape of the writer as a man.

This has hardly been the prevailing approach to the writer’s work in Italy over the years. Italy and Scott Fitzgerald have always been at odds with each other. If we wish to assign a mythological root cause to this problem, in the vein of the ancient Romans use of Dido’s abandonment by Aeneas to justify why they were the target of such hatred by the Carthaginians, we could say that everything started in 1924 when the intoxicated writer punched a Roman taxi driver. In reality, Scott Fitzgerald’s publishing history in Italy is a very complex one and was dependent on the main literati and critics who were granted the right to speak on American culture in the 20th century: Elio Vittorini, Cesare Pavese, Fernanda Pivano and Nemi D’Agostino, just to mention a few.

Scott Fitzgerald’s first published work in Italy was Gatsby il magnifico, released in 1936, in a monthly series by Mondadori, “I romanzi della palma”, in a bizarre translation by Cesare Giardini. These are the words used to introduce it, “This book… documents the deep social moral and financial unbalance dominating and determining life in the United States from the end of WWI to the Great Crash of 1929”. However, we are immediately struck by an obvious discrepancy: The Great Gatsby was published in the US by Scribner & Sons in 1925, smack in the middle of the Roaring Twenties. Perhaps, this description would have worked better for a novel such as Tender Is the Night published in 1934, after the Great Crash.

At any rate, Scott Fitzgerald was practically ignored by the Italian critics and even Elio Vittorini didn’t seem to recognize his importance when he included him in the Americana anthology (Bompiani 1941) in the chapter Eccentrici, una parentesi, together with the by now forgotten Kay Boyle, Evelyn Scott and Morley Callaghan. This was his first officially stamped appearance, yielding, however, much the same results as his first one in 1936. Elio Vittorini considered Scott Fitzgerald a frivolous writer who had little to do with his own magic vision of the mega continent. In the critic’s own words “… in this legend [America] is a kind of new fabled Orient, though a man may appear there under the sign of an exquisite particularity, which makes him a Filipino or a Chinese, a Slav or a Kurd, that man is substantially always the same lyric subject, the protagonist of creation”. The short story included in the Americana anthology and translated by famed poet Eugenio Montale with the title il giovin signore (from the original The Rich Boy of 1926) shows that the lens used to interpret the writer was completely distorted. His story is seen as one of the inner unraveling of a rich, young American man due to unrequited love, general moral dissipation in the background. Outside, instead, stand the shadows of tragic reality: unemployment, strikes, the economic crisis … the very stuff of socially oriented literature.

The problem, as Fernanda Pivano was later to point out, is that no work of Scott Fitzgerald can be fully understood without taking into account his biography. Like Hemingway said in his memoir A Movable Feast and as confirmed by Scott Fitzgerald himself in The Crack-up (published in Italy as Il crollo in a translation by Ottavio Fatica, Adelphi 2010), the writer had two or three experiences in his life to which he has assigned universal value. These included his meeting with Zelda Sayre. The Rich Boy was nothing but the hypothetical treatment, and a potentially autobiographic one, of a parallel existence in which the girl rejects the boy, this time forever.

The sincerity with which Scott Fitzgerald plays with himself is truly great proof of how much, in American culture, Pirandello’s lesson on literature is turned utterlyupside down: instead of interrogating themselves on the distinction between Life and Fiction in the US the life/fiction duality is practically inextricable. Vittorini’s second mistake lies in the fact that he saw Hemingway (Scott Fitzgerald’s best friend) as the triumph of his own vision: to him America was a gigantic non place that made it possible for it to speak in the name of the whole of humanity. As a result, any published work could be misread as far as literary genre and be considered Poetry. As we shall see later, though, Scott Fitzgerald, perhaps more than any other American writer, displays in his work what an Italian critic was to call magic realism.

Scott Fitzgerald’s success in Italy started with Fernanda Pivano translation of Tender Is the Night (Einaudi 1949), translated by her at Cesare Pavese insistent request, as can be seen in a letter that he wrote to his friend Davide Lajolo: “I did not want to translate books by that writer […] because I liked him too much”. Mondadori then bought the copyrights to his other works, which were published later in a scattered order compared to their actual chronology. The Great Gatsby, This Side of Paradise, The Beautiful and Damned were all translated by Fernanda Pivano while the unfinished novel The Last Tycoon, titled in Italian Gli ultimi fuochi was translated by Bruno Oddera. In an attempt to debunk the myth that Scott Fitzgerald was the main representative of the Age of Jazz, in the Foreword to the four novels she translated, Pivano always insisted on two specific concepts, i.e., that what was previously seen as Realism in his style should instead be interpreted as poetic and that parallels should be drawn between his fiction and his private life. Thus, he’s not a mirror of a specific society, but the faithful portrait of himself as character that moves in that particular society, while overtaken by a drama that is completely personal and individual.

This marked a turning point leading the way to an actual debate about the writer in the most important Italian literary journals of the times. Carlo Izzo took on the main adversarial position when he stated that perhaps time would reduce Scott Fitzgerald’s figure to “more modest proportions than those that more modern critics tend to assign to him today”. Fortunately though not everybody thought the same. Luigi Berti in the journal La fiera letteraria took the first important critical step against the myth established by Vittorini, claiming that contrary to that critic’s assessment, Fitzgerald is not at all a lesser figure compared to Hemingway. The fatal blow, however, came from Nemi D’Agostino who in the journal Studi americani defined the writer’s style using the term magic realism. The legend of America theorized ten years before by Vittorini had now been fulfilled precisely by one of those “eccentric minor writers”.

And finally Fitzgerald was accorded academic recognition: in 1958 Sergio Perosa published the first huge monograph on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work followed by a series of translations of his minor works until his novels were published in a Complete Works format edited by Fernanda Pivano for Mondadori in 1972.

In these past few years, interest for Scott Fitzgerald has grown all over the world: the recent movie Genius by Michael Grandage (2016) is proof (even though it is a movie) of how the myth of the writer as a caricature of the Roaring Twenties, seen for example In Woody Allen’s movie Midnight in Paris (2011) is just about to run out. Though Fitzgerald appears only as a secondary character in that movie, there is a clear attempt to faithfully reproduce the psychology of the real man. And even in Italy a number of his works that testify to the writer as a man are now being published, i.e., his entire minor works together with his private documents. Hence, we now have all the needed tools for a more accurate approach to criticism of Scott Fitzgerald’s writing. In this book we shall attempt to suggest a specific interpretive lens for his work.

Translated from the Italian by Pina Piccolo

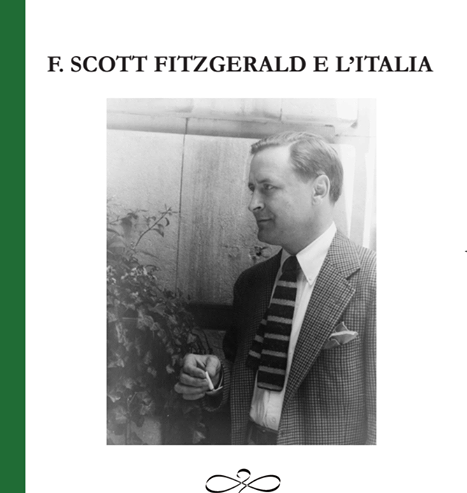

Born in 1994 Antonio Merola earned a Masters’ Degree in Italian Literature from the University of Rome La Sapienza. He has published the volume F. Scott Fitzgerald e l’Italia (Ladolfi, 2018). He is co-founder of YAWP: giornale di letterature e filosofie, for which he served as editor of the poetry anthology L’urlo barbarico (A. V., Le Mezzelane, 2017) and manager of the Yawp Poesia section. He is curator of Quaderni Barbarici on the Patria Letteratura website, a space devoted to the unpublished poetry of contemporary young poets, as well as of Razzie Barbariche on the Pioggia Obliqua website, a space reserved to published work of poets under 30. His poems have appeared in important Italian online journals such as A4, Nazione Indiana, Atelier (paper and online), Pioggia Obliqua, Poetarum Silva, Il Foglio Letterario, Argo, Nuova Ciminiera, La Tigre di Carta, Pageambiente, Euterpe e La Macchina Sognante. He contributes or has contributed to Altri Animali, (Racconti Edizioni), Flanerì (where he is editor of the column L’isolamento del romantico americano), Lavoro Culturale, Carmilla e Culturificio. His short stories have appeared in Nazione Indiana, Carmilla, Argo, Cultora, Frammenti Rivista, Il Pickwick e Reader For Blind.