Indigenous artists from the state of Roraima in Brazil fight for rights of their people, that’s why they call themselves Artivists. I received their invitation to contribute an essay to be included in an e-book designed to honor Jaider Esbell and Grandma Bernaldina. Receiving this invitation flattered me and worried me at the same time, because the act of transforming words, feelings, events into a written text always involves complicated, sometimes painful, inner work.

I lived in the state of Roraima for many years, always working with or on behalf of the indigenous population. I use Internet every day to stay in touch with that region, to champion and disseminate the achievements of our relatives, the indigenous people, to raise public awareness of the territorial and cultural rights of Brazilian native ethnic groups. One day, I came across the creations of Jaider Esbell, which I found most intriguing and fascinating. In 2016, for the first time, three indigenous artists participated in the Pipa Award, in the Online category. The winner of this competition is decided on the basis of the number of votes received on their page on the Prize website, and the aim of the initiative is online promotion of the nominated artists and Brazilian contemporary art as a whole. The indigenous people and their allies launched a campaign for the three artists and I did my part. Of the sixty-three participants in the first round, only ten got more than five hundred votes and moved on to the second round; among them were the three indigenous artists. Jaider Esbell ended up being the winner, Arissana Pataxó placed second, Isaías Sales won third place. On that occasion Jaider expressed his satisfaction with the popularity of his work, was elated that through the competition he had reached a greater number of people to whom he was able to present the reality and culture of the Macuxi people, the indigenous group he is part of. Also, in 2016, Jaider friended me in Facebook so that despite the geographical distance, we had the opportunity to engage in dialogue and interact. I met him in person during a stay in Roraima in December 2018, and together with a Macuxi colleague he interviewed me for a local radio.

Jaider appeared on the activism scene through his art in 2011 when he invited Carmézia Emiliano, Bartô, Amazoner Arawak, Luiz Matheus, Diogo Lima, Isais Miliano and Mário Flores Taurepang to reflect on the sensations that the natives of Roraima might have felt when they had the first contact with cows brought to their lands by the white invaders. Composed of sixteen works, including nine by Jaider himself, under the title “Cows in the land of Makunaimî – From cursed to desired”, that collection has become a milestone in the history of contemporary indigenous art in Roraima. Since that time, Jaider’s participation in a large and most diversified number of exhibitions and events intensified throughout Brazil, and he never failed to invite other artists to participate in the activities he himself organized.

Beginning in 2013, Jaider Esbell started touring European museums, championing the need to save and preserve the founding principles of indigenous art. In 2019, alongside artists Daiara Tukano and Fernanda Kaingang, he participated in several international exhibitions in ten countries, developing concepts that encompass a critical re-envisioning of European hegemonic art and suggesting strategies to free contemporary art from the interference of colonization. Acting in a multiplicity of interdisciplinary ways and performing various functions, throughout his wanderings Jaider also engaged in daring rituals and performances, both in Brazil and abroad. Because of his histrionic and provocative style, not everyone felt comfortable with him, or got his message completely. However, his work, his videos, his words, his feverish and tireless activity have attracted public attention to the dramatic situation of the Brazilian indigenous peoples and have paved the way for other indigenous artists.

The 34th São Paulo Biennal was held from 4 September to 5 December 2021. Simultaneously, from 4 September to 28 November, the MAM – Museu de Arte Moderna hosted the collective show “Moquém_Surarî: contemporary indigenous art” curated by Jaider. The exhibition brought together the works of thirty-four indigenous artists. On November 2, the news of the unexplained, untimely demise of the Macuxi artist struck like a bolt of lightning out the blue. Practically, the history of the biennial and the collective is based on his thought and its articulation. Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, general curator of the Biennal declared: “Jaider Esbell was a generous and committed person, with an impressive ability to establish bonds and build bridges between the most diverse people, communities and knowledge. He will be deeply missed. Inseparable from his brilliant artistic production, he leaves an unsurpassed legacy of struggle for the recognition of the value of the cultures and life of indigenous peoples. In October 2021, the Center Georges Pompidou, the Beaubourg, had announced the acquisition of two works by Jaider Esbell : Letter to the Old World (2018-2019) and In the land without evils (2021). The curatorship of the 59th Venice Biennale has selected the Macuxi artist to complete the International Art Exhibition entitled “The milk of dreams”, open to the public from 23 April to 27 November 2022. I’m sure that Jaider’s spirit will arrive in Venice to provoke and disrupt the hearts and minds of the organizers and visitors of the exhibition.

As of this writing, São Paulo is about to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Week of Modern Art, as it took place there between 11 and 18 February 1922. That event became the emblem for Modernism, a movement characterized by the work of painters who had spent time in Europe and had taken with them the influences in the art created there. Anthropophagy, that is, the practice of cannibalism, was an obsession of the Parisian avant-garde in the 1920s; hence, Modernism preached that Brazilian culture would be resurrected by “digesting” external influences. The writer Oswald de Andrade showed the poet Raul Bopp a painting made by his wife; in the enigmatic figure painted by Tarsila do Amaral the two saw a cannibalistic indigenous man, an anthropophagous man, someone who would devour culture to take possession of it and reinvent it. In a dictionary of the Tupi-Guarani language, Tarsila found the words “aba” and “poru”, which mean “man who eats”. Entitled Abaporu, the painting has become the most iconic piece of Brazilian art.

Historically, anthropophagy has also been used to justify the extermination of Brazilian natives. White men invaded territories, massacred peoples, devoured the very foundations for the physical and cultural survival of the indigenous people, ate forests, poisoned habitats and rivers, drank the blood of the natives murdered or killed by epidemics and deprivations. After five hundred and twenty years of violence and abuse, there are still indigenous peoples in Brazil who insist on surviving thanks to their formidable resistance. I deeply believe that any manifestation of art is a political act. Being our contemporaries, today the Brazilian indigenous people are also fighting for their rights through painting, sculpture, photography, literature, poetry, theater, song and dance. They are achieving two results at the same time: their efforts add to the struggle for the physical and cultural survival of their ethnic groups and are helping to redefine national identity, as Brazil cannot exist without its indigenous peoples.

I would like to conclude my tribute to Jaider by turning my thoughts to the cows of the lands of Makunaimî. At the time when the Roraima Dioceses implemented the project “Uma vaca para o Índio”, it was widely questioned. It was thought that, in order to be recognized or receive approval, the indigenous people did not need to develop economic activities in the territory they historically and traditionally occupy. Gradually, however, it was precisely through the activities that until then had been controlled by the invaders of their lands, that the indigenous people of the Roraima lavrado ensured means of subsistence, well-being and economic autonomy. In 1922, intellectuals and artists thought they had digested external influences and reinvented Brazilian art. The contradiction lies in the fact that they were influenced by the Parisian avant-garde which was obsessed with cannibalism. In 2022, the spirit of the thinker and Macuxi artist Jaider Esbell is heading to Venice to tell the world about the re-birth of Brazilian art after its being devoured and reinvented by the indigenous artists themselves.

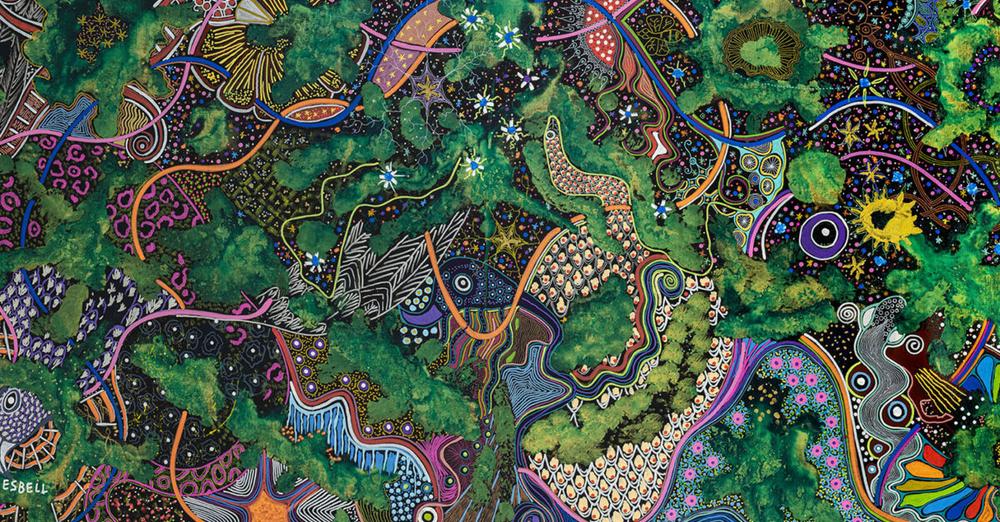

Titles of paintings in the gallery:

“Mereme’ – A origem do arco-íris e seus mistérios”, 2021, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 112 x 160 cm.

“A descida da pajé Jenipapo do reino das medicinas”, 2021, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 111 x 160 cm.

“De onde surgem os sonhos” 2021, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 112 x 232 cm

A conversa das entidades intergalácticas para decidir o futuro universal da humanidade”, 2021, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 112 x 232 cm.

“Arikba, a mulher de Makunaimî”, 2020, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 72 x 75 cm.

“Curandeiro Trabalhando com Tabaco”, 2020, Acrílica e posca sobre tela, 70 x 70 cm.

Loretta Emiri lived in the Brazilian Amazon for eighteen years, working with and for indigenous peoples including the Yanomami. She has published the Dicionário Yãnomamè-Português, the poetic collection Mulher entre três culturas, the ethno-photographic book Yanomami para brasileiro ver. In Italian, she wrote Amazzonia portatile (Portable Amazon), Amazzone in tempo reale (Amazon in real time, special jury prize for Nonfiction “Franz Kafka prize Italy 2013”), A passo di tartaruga -(At a Turtle’s Pace)In May 2018 she was awarded the special career prize “Novella Torregiani – For Literature and Figurative Arts”. In 2020 her book Mosaico indigeno(Indigenous Mosaic) was released by Multimage press.