In Italy, conversations surrounding race are left to the past due to their negative connotation and connections to fascism, colonialism, contributing to “evaporations of race” in language. However, race, racisms, and silencing exist on macro-and micro-levels. Italian laws on citizenship and immigration racialize and institutionalize bodies as others, describing them as a “threat” to the “security” of a nation. Youth who seek citizenship still must wait years to become eligible, and the Italian government decided to continue financing corrupt, colonial relations with Libya to “manage” people traversing the Mediterranean sea. The Mediterranean continues to be a space of genocide, echoing the transatlantic slave trade, where human lives transform into numbers and media headlines. Willy Monteiro Duarte, Idi Diene, Abdul “Abba” Salam Giubre, Loveth Edward are among the many humans murdered, assaulted and disregarded by white supremacist impunity. These examples of macro-level violences exist along with daily wounds like microaggressions.

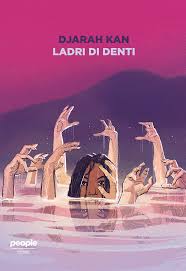

The seven fiction stories and essays of Djarah Kan’s Ladri di Denti address how people are silenced through everyday racisms, ultimately infecting their psyche and intimate relationships. Kan’s stories address the entanglements of race, gender, class and sexuality in Italy through daily, everyday racisms and microaggressions. Like in many of Kan’s essays and stories in Futurel, the localities are in Campania, specifically Naples and Castel Volturno. Elena Ferrante’s novels have catapulted a romantic vision of Naples internationally, whereas within Italy, many writers of African descent are either from or based in northern Italian cities. Kan’s perspective shows aspects of life in Campania that aren’t typically represented in media storytelling. Some protagonists are able to begin to resist the pain from the wounds of racism and white supremacy. Others are at the beginning of their journey. In this article, I focus on how the stories unearth pains of morphing oneself to fit within the white gaze, sexualization of the Black bodies, and the power of speaking back.

In “Gli ultimi giorni dell’agosto”, the unnamed protagonist, an adopted mixed race young woman in Naples, pieces together the learnings of a tragedy of someone important to her. The protagonist’s family, who lived in Veneto for decades before moving back to Naples, have their own histories of violence that shaped their patterns of abuse and racism. When the father learns about the sinking of a ship carrying people traversing the Mediterranean sea, he reacts, “And so what? All of this will never end. Do they all really want to come here?”(«E che dobbiamo fare? Tanto ’sta storia non finirà mai. Tutti qui vogliono venire?» p14). These everyday racisms impact the protagonist and shape her own internalized racisms. As a child, she dreamed of straight, blond hair and blue eyes, and as an adult, she describes Black women who seem like a threat to her as whores. In this layered story, Kan demonstrates the trauma of being forced to identify with whiteness and how that strips multiple characters of their humanity.

Comparatively, in “Santa and Jess”, the protagonist, Jamilah, struggles to maintain relations with her white partner and classmate, Santa. Jamilah’s dedication to Santa raises questions about the lengths people will go through to disregard how their humanity is denied. Whether silently witnessing a white woman touch a Black baby on the mother’s back, or being told “she’s smart and not like “them” (in regard to media depictions of immigrants on tv), Jamilah deals with numerous episodes that silence her reality and force her to fit within the white gaze. As Jamilah makes sense of the series of events, she begins to pursue her own journey to resist and claim her narrative.

In “La storia di Topo”, we are told Topo’s story through the eyes of the young protagonist and her mother. Italian immigration laws that leave him in a constant cycle of dependency on the Italian state, including centri di accoglienza. Kan questions the “good deeds” of the white people who manage these state-run centers, and the opacity of violence and silencing that occur in these spaces.

In “Cacciatrici di negre”, the narrator reflects on the sexualization of her own woman-identified body. She tries to make sense of the vicious attacks of her masculine classmates calling her a whore, assuming she’s one of the African women working the street at night, and the girl next to her in class looks at her as if “she is guilty of something”. These violent acts recall Italy’s colonial past of madamismo in the late 1930s during the period of racial laws. Kan investigates the timelessness of exoticising the Black body, and how Black women see themselves as a group and individually in Italy.

Compared to the narratives in the collection, two essays unpack the colonial visions of Africa and Blackness in Italy, “Conosci la tua storia” e “Il re leone”. The former critiques white folks who have read one or two books related to the African diaspora, and believe that they can educate other Black people about history. Whereas the latter challenges readers to think beyond colonial depictions of the continent. These essays speak to processes of de-colonizing the self and piecing together the fragments of trauma.

Speaking back is not limited to those that are physically present on the planet. The Mediterranean sea has become a space of genocide, recalling the transatlantic slave trade. “Spiriti” reminds us that any being that has lived can still communicate with the living, even if they were stripped of their humanity when they were alive.

Kan exposes the fragility of whiteness in everyday relationships in Italy, and how it thrives and persists on dehumanization of Black people. Kan’s stories and essays push her readers to ask: When will people deemed as “other” be recognized for their humanity?

Candice Whitney is a researcher, writer and international education professional based in New York City. In 2016-17 as a Fulbright Scholar, she conducted research on how the historical and political processes that shape Italy’s contemporary relationship with African countries impact the promotion of products and business relations amongst African women entrepreneurs in Italy. Candice received her Bachelors of Art in Anthropology and Italian from Mount Holyoke College. More about Candice’s work can be found on her blog.