“…within my own work that I like best are places where I experienced a sense of mystery—rather than mastery”

I thought I was reading but suddenly I’m read. Some

kind of artist then, painting his targets. Distinct or in-

distinct sensation? I prefer clarity when I can afford it.

So what if another flower plagiarized the rosary? I’d

pick up a dime in private or a quarter in public, mon-

ey’s always been ‘dirty’, some kind of death wish. Sure

I’d like to own a pet, not own but take care of, not a

monkey or donkey, but something that loves you like

money or luck. Not a puppy made of flowers but like

music, in dog years.

(The Principal Catastrophe, Elizabeth Willis)

When I asked Elizabeth Willis about her own vision of the world that is reflected in her poems, she humbly isolated the words ‘surrender’ and ‘capture’ I used in the question, criticizing them for echoing the language of war, and ownership. No wonder why the rest of the conversation saw our mild debate about the concept of ‘authorship’, which I till date believed, represents the ultimate signature of a poet and she is slightly indifferent about. She repeatedly emphasized the importance of a poet’s sincere effort to utilize the best way possible the resources she/he has. The statement sounds undeniably startling, if not shocking especially because Elizabeth’s poems unmistakably burst into indomitable novelty; a reader can sense her presence in everything she attempts to write. This was, however, my interpretation and as usual in our four-month long conversation we did not reach any unanimity in opinions, though, at the end of the day I must say, I was left profoundly influenced by her exceptionally liberating ideas.

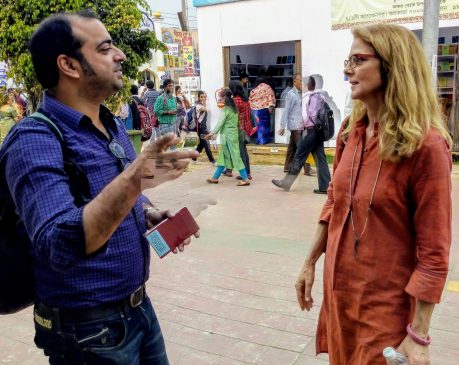

The first time I met her was in a February, 2019; during the Book Fair – at a café in south Kolkata where we arranged her very first reading in the city. If one is resolved to find the element in her works that particularly perplexes the readers, one does not need to go far from recognizing her unique style in presentation, and as that presentation does not follow any fixed formula, the reader has to give in to an overwhelming sense of mystery that is perpetually involved in her writing process. For example, here are a couple of poems she read at the café that evening: the first one is titled – ‘About The Author’-

About her: the air, warm as fact.

An imaginary boat heading off to hell, her foot pushing it offshore.

The sunlit bank, a mirage of the perfect past.

She was barking at the waves, thinking they barked first.

But this was not a river. It was Thursday, a word cast in lead.

Her eye had turned the water into sky.

The poet is a trespasser.

The poet is the king of Rome, New York, with one foot in a boat and one against the snowy shore of reason.

Wondering if, like a boy, she could go there for a season.

And the second poem is ‘A Species Is An Idea’

Leaving my umbrella

I left everything behind

That dog, an emblem

of my dirty self

All this reflection

amounting to shadows

Ink eats the page:

it’s Chemistry against the Forest

What train are you on

with all these thoughts?

What bitter landscape

the better to hear you with?

Its stepless grid

is suddenly a corridor

You write this down

You’re at the end of it

Each time I tried to ask her about a poet’s necessity of having a unique voice, she firmly said the most important thing for a poet is not to try to stand out but to attempt to stay afloat in the rich tradition full of echoes of great writers. She wins over the debate with the highest standard of argumentative rigour: “If you see yourself as part of a lineage and community—though not necessarily a “tradition”—then in a sense your entire work is only a portion of something larger. So it’s less important to stand out than to carry on the work in some way”. Having said all that, what still remains inexplicable is how someone, if he/she does not have a ‘vision’, a mastery over one’s own way of seeing and interpreting the world around, can write a poem like ‘Address’, which runs:

I is to they

as river is to barge

as convert to picket line

sinker to steamer

The sun belongs to I

once, for an instant

The window belongs to you

leaning on the afternoon

They are to you

as the suffocating dis-

appointment of the mall

is the magic rustle

of the word “come”

Turn left toward the mountain

Go straight until you see

the boat in the driveway

A little warmer, a little stickier

a little more like spring

It is simply impossible to argue against a reader who claims his/her reaction to Elizabeth Willis’s works is chiefly related to a sense of utter amazement. As our conversation progressed I felt we both were addressing the same thing, but from two different directions. Elizabeth’s view explores the complex nature of ‘originality’ in a poet’s voice – it is not being detached from what thousand others are doing – rather being a part of it with a full consciousness of one’s own capacity. It is the most important message to a poet from a poet.

অরিত্র সান্যাল

Aritra Sanyal in conversation with Elizabeth Willis

Aritra: Elizabeth, in a poem of your book The Human Abstract (1995) there is a line that made me stop at it: ‘Direction a by-product of wandering…’ As I was about to plan a route through which I wish our conversation to travel, I am tempted to focus on this single line. Firstly, because I wish to know your response if the line is seen as a metaphor for a poet’s editing of a poem during the process of writing, and I wish to know if you think of editing as a conscious act or an arbitrary one. The second part of the question is: Do you imagine yourself as a completely different poet from what you are today?

Elizabeth: Aritra, that’s such a thoughtful way to begin. Yes, as I think you’re suggesting, that line could be read as an ars poetica. To begin by wandering is to admit that one doesn’t know the way and must actively engage with whatever comes along. I often think about the histories of conquest —and the repercussions of those histories— and about the importance of poetry in establishing patterns of relation that create other pathways than the ones history has already generated.

If I follow your suggestion of reading the line as a metaphor for the writing process, I suppose I would emphasize that I’m not proposing directionless or objectless poetry—but that if we admit that the situation of the poem is always in the process of emerging, the poem has a better chance of finding new meanings, even new ways of being, than if it is moving along and reporting on the same well-mapped routes. I think this could apply equally to certain kinds of activism.

There is so much more we could discuss here. What motivates a poem is an ethical question every poet handles in different ways. If a poem is serving the poet —written to impress others—it is almost certainly doomed to uphold the status quo. On the other hand, if it serves language itself, it will keep both the reader and writer at the threshold of an emerging understanding.

This is where some kinds of conceptual work seem to me to fall short and other kinds are more generative. If a poem is merely fulfilling a conceptual plan, I often find it dull, but if it is working with constraints in order to force the poet to use language differently from their habitual patterns, the results can be quite powerful.

To answer your other question, there is a lot of formal variation in my work, but I think that at heart I’ve continued to be concerned with very similar things. Poets are always responding in some way to whatever surrounds us, which means that both the sound and the cognitive and political demands of any moment will call forth a poem that may not sound or look quite like anything that has come before it. I don’t think the process is arbitrary at all—but at its best it goes beyond the reach of conscious effort.

A: Your works repeatedly show your profound engagement in paintings. Drawing pictures with words is not so uncommon a thing but reading a poem in Turneresque (2003) ‘Grammar is coral/ a gabled light/ against the blue/ a dark museum/ Durable thing’ a reader may get curious to know if you have ever tried to write colors? How the world surrenders to you when you try to capture something while writing?

E: Because visual art approaches questions of representation in ways that are quite different from the ways language approaches them, I find art often helps free up my thinking about writing and translating the world. By writing colors do you mean a kind of synaesthetic experience? I don’t think I’ve experienced anything quite like that but there is an unboundedness to sense experience that often makes me want to reach beyond a single method or art form. It’s interesting to think of this in terms of “surrender” and “capture” since we often think of language or art as “capturing” something. But I hear in those terms an echo of the language of war and of ownership, which makes me wonder if there’s also a way for us to imagine an art that releases something (perhaps even in the process of trying to capture it!)—or maybe it captures us as much as we capture it. I would love to hear what you think about this.

A: Is ‘authorship’ a bad thing? I believe every poet with an individual voice is bestowed with a filter through which she or he expresses how the world or life is experienced. The poem I quoted in the previous question has some ‘Elizabeth Willis-element’ in it in the sense that this is something only you could produce. If something that art releases can capture us, I think it does so because we let it do so. Otherwise, how can one explain the difference between two poets’ reaction to the same thing? Meanwhile, I would like to go back to your first response in this conversation where you talk about the limitations of certain kinds of conceptual work: they tend to fall into a loop of a certain schematic patterns of writing poetry. While fully agreeing with you on this, I must say I found this view quite interesting. You are associated with arguably the most famous writers’ workshop of this planet. A workshop must prescribe some general patterns as it addresses a bunch of writers. How is a poet / writer supposed to thrive with his individual talent in that situation?

E: I don’t consider authorship inherently good or bad. The question is always what one does with what one has. Because of the ways authorship involves access to certain resources and powers, I think it comes with a certain responsibility not to waste those resources, including other people’s time. I mean, there are plenty of people who have access to the means of production, who can publish more or less whatever they choose, but publication in and of itself is not the measure of value. Emily Dickinson is a great example of this, as she managed to publish so few poems during her lifetime, yet her work has had a tremendous impact in showing American readers a way out of certain kinds of conventional thinking. But there are so many other poets whose work is unknown to the literary establishment—and even if those poems never make it into a broad public readership, I believe they have an impact on the history of human consciousness. By the same token, there is so much work being published that not only squanders those resources but is reactionary in terms of its effect on its readers. I want to be the kind of writer who, at the very least, does as little harm as possible—and, I hope, opens a few portals.

It’s true that for the past few years I’ve been teaching at a famous writing workshop, but its role is not prescriptive. It does involve attention to craft and discussion of poems and literary history, but its primary mission is to support the work of emerging poets and to offer an environment where exceptional writers can learn from each other. The model of the artist’s workshop comes from the medieval guild and ideally it should maintain some aspect of shared labor and communal commitment. It may seem paradoxical but I think poets learn more from the time they put into discussing the poems of others than they do from the comments they receive on their own poems. It really is a situation in which the more attention you give to others, the more skill you bring back to your own work. In the admissions process, we’re not primarily interested in the most polished writing but the most promising writing, the work that is doing something all its own rather than reiterating or reprising the kind of work that’s already been done.

A: How important it is for a poet to have her or his own voice and style in poetry? The reason why I land on the question comes from my unending curiosity and confusion about the resources a poet has. Does it depend on what resources you have or what you do with the resource? In your interview with the gulfcosatmag.org (http://gulfcoastmag.org/journal/25.1/a-poem-argues-for-its-own-existence-an-interview-with-elizabeth-willis/) while explaining the occasional references to great poets and forms of poetry you emphasized a synthesis between your own work and the tradition, and you said you tried to build a new architecture out of the ones you inherit. A negotiation between one’s way of experiencing life and the way it is expressed in other poets’ work whose influence on him/her continues. But doesn’t there remain an indomitable desire to stand out somehow?

E: I find questions of voice in relation to tradition and literary influence very interesting. I don’t find the “desire to stand out” a driving force. For me, the primary desire is not to stand out but to fully do the work that I’m able to do, to bring my best thinking and listening into the world of the poem. Maybe the underlying question is what is the unit of poetic composition? Is it the poem? the book? the life-work? If you see yourself as part of a lineage and community—though not necessarily a “tradition”—then in a sense your entire work is only a portion of something larger. So it’s less important to stand out than to carry on the work in some way. I suppose this may sound like a Romantic concept of poetry—I’m just interested in taking the discussion of poetic voice outside of the realm of what is marketable as an individual style.

The process people refer to as “finding a voice” is very complex because none of us has a voice that is entirely detached from our culture or class or family structure. It’s impossible. That’s how language comes to us, and that’s how we use it; it has a social history and a political history as well as an emotional history that’s rooted in our experience but also in everything we’ve grown up hearing. In my experience, the process is less about finding myself than about finding the voice of the poem. I don’t think any of these things can be separated from our conscious experience, what and how we see the world around us. Maybe that’s my version of “voice”: it’s what one brings to the page that is shaped by what is both internal and external to the poet. I’m probably belaboring this, but I think the passages within my own work that I like best are places where I experienced a sense of mystery—rather than mastery.

A: Probably my question addressed the insecurities common in poets who think they have not got the response they wished to have. Now, the number of people in this group is huge, probably everywhere. This is a strange situation especially when we have this towering impact of social media which has fatally threatened the role of print media; where even a mediocre ‘post’ garners several stock reactions: love, anger, wow, sadness… We have a social media star Rupi Kaur… anyway, Elizabeth, the question is: how will a young poet deal with the situation if there is no reaction to his/her works?

E: Almost every writer has to grapple with this issue at some point—young or old, published or unpublished. This is how I understand what Keats called “negative capability”: as the ability to write with your full human capacity, even when circumstances around you are actively making that work more difficult. This means defying your own doubts as well as those of others. You have to persist with what matters to you. Sometimes it is helpful to remember that receiving a lot of attention or having a large readership does not always lead a poet to write their most significant work.

A: We have seen poets have written on paintings again and again, (Auden, William Carlos Williams, Szymborska, to name a few). How do you experience the nature of the equation between these two art forms? All the Paintings of Giorgione (2006) is a startling example. It made me feel you are taking us in a tour to a gallery, and writing down the brief descriptions of the paintings. It is brilliant, exhilarating, enlightening. The course of history is recounted in a very striking way. Does poetry inspire newer interpretations of the paintings or overwrite its already existing implications?

E: What I find exciting about painting is the way that it deals explicitly and materially with form and medium. Because the poet’s medium is language and we live in a sonic landscape of human communication, poets have to deal with the formal bounds of a poem in ways that tend to become more abstract. Painting, on the other hand, is a bounded space. It ends and begins within a formal frame. So it has to deal concretely with its own frame structures, and it has to use its own means of directing our attention. It can imply narrative and lyric patterns, but it does so silently. So it generates an open space for language to engage with and interpret it, which can involve both inspiring new interpretations and overwriting existing implications.

For me art museums and libraries are sacred spaces in similar ways: sites for exploring the consciousness that comes from looking at the ways others have seen, ingested, submitted to, and transformed the world through their perception of it. It’s something I find curious about our species; why do we feel compelled to perform these acts of imagination, invention, and translation? My sense is that it is crucial to our survival as a species —and it is crucial to helping us find our way out of the troubles we get ourselves into. It is why artists, in the broadest sense, have a responsibility to exercise their imagination. It’s not mere self-indulgence or individual voice; at its best, it has a social and biological function as well as other more professionally recognized functions.

A: Speaking of tradition, who do you think has / have influenced you when you started writing? When did you start? I wonder if the world was a worse place then. What can a poet do against this madness when there is a surge of despotism in the global scenario… It is an old question perhaps, and perhaps it has refreshed itself in the worst way possible now.

E: I started writing poetry shortly after I learned to write, when I was about five years old. For me it has always been a vehicle for exploring and improvising with sound and meaning. Was the world better then? The ruinous effects of the Anthropocene were less obvious, so I suppose it looked better, but I doubt that it was better.

How can we talk about the particular kinds of madness that creatures of all kinds are experiencing globally? Other species have been demonstrating the effects of our actions for a long time. Monsanto knows that its genetic modification of seeds is disastrous for the biome; but that disaster may also, to their corporate mind, be yet a further opportunity for profit. Dow understands the effect of its chemicals on the DNA of plants and animals (including humans) but its vision, like Monsanto’s is focused on how the evolving disaster of the natural world can be capitalized. Both of these companies put millions of dollars into ad campaigns that make them sound like they are environmentally progressive, but whatever good either of them may do on any front, it is tiny compared to the harm they’ve already perpetrated.

I fully believe that devotion to profit, that willful blindness to the effects of one’s actions, is inseparable from other forms of organized and calculated despotism happening all over the world. What the primary figures in the US and UK have in common, just to take two, is the appearance of random buffoonery, but it’s a show with an underlying agenda that is bent on demolishing human agency in the interests of political control—including the control of increasingly endangered resources like clean water. What once were considered rights (say, of clean air and water) are more and more unevenly distributed than ever.

Yes, this too is about subjectivity, agency, and voice—the voice of individual subjects and of endangered communities. When what one recognizes as truth is referred to as “fake” news, the very grounds of art and imagination are being called into question—and both truth and artifice are under attack in very, very dangerous ways.

The ways that art can show the meaningful deployment of artifice and its relation to documentary experience don’t blur the boundaries between what is real and what is fake; they may call them into question, but ultimately they enhance our understanding of the relation between the real and the artificial. This, to my mind, is one of the ways the making of art is linked with our survival.

A: What, according to you, is there in poetry, or so to say, in literature or every form of art that resonates with the reader or the audience? Is it empathy?

E: I think it is mystery and curiosity more than empathy. What makes me slightly suspicious of empathy is that I think it suggests that one being knows–that they can and do know–what another being experiences. It seems to me entirely possible that that might happen in a mystical sense but not in a narrative sense. That is, I might relate to, or identify with, or have sympathy for another person’s experience, but I can’t know everything that informs it.

As we’ve been talking, I’ve often thought about how many resonances there are between our perceptions about poetic and political reality. But I hope I never presume to know, empathically, what you experience. It seems more appropriate to respect the differences as well as the similarities in what we know–what Frank O’Hara calls “the love we bear each other’s differences.” America and India both exist in post-colonial struggles, but the timing and the arc of those struggles are distinct for both countries. And not just the countries, but for specific regions and languages and familial situations within those countries.

My sense is that we do not yet know the name for what binds us as fellow humans and as fellow creatures in this strange historical moment. So much of history has been written according to national units, but I think we are beginning to understand that not only is the fate of all humans connected, but the fate of all living things is connected in ways that heighten our responsibility to respect what we don’t know about the experience of others beyond understanding that our fates are profoundly linked.

A: What is your favourite time of the day for writing?

E: Morning! Before I have had time to censor myself.

A: Elizabeth, how important it is especially for a beginner to be experimental in writing? Looking for newer avenues, treading the untrodden paths can be exciting like adventure. But can experimental writings form a separate genre? In Bengali literature, it is very unfortunate; we cannot claim any gifted writer has tried his/her hand in experimentation…

E: It is so hard to say what is important, since I think that is different for everyone. I wouldn’t prescribe experimentation any more than I would prescribe a strict understanding and practice of poetic forms. I think a poet can write brilliantly, fearlessly with or without formal strictures.

If I am hungry and there are only three things in my refrigerator, I think about how best to combine them. That is experimentation too–and it can generate interesting results.

Terrance Hayes came out with a gorgeous book of sonnets last year called American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin–and they really are sonnets, but they are also experimental and politically charged and deeply relevant to our moment.

A: Will you like to name a few contemporary American poets who we should be reading? The best I could do about it was to buy a copy of the annual series of The Best American Poetry…

E: There are so many great poets writing now. Some of my favorite writers who are around my generation or slightly younger are Fred Moten, Simone White, Lisa Jarnot, C.A. Conrad, Anne Boyer, Terrance Hayes. Jen Bervin is doing great interdisciplinary work. And I’ve been very impressed by what some of my former students have produced–some of whom have crossed from poetry into the visual arts: Julian Brolaski, Ben Krusling, An Duplan, Cameron Rowland. But I hate to make lists because I know I’m leaving out so many people! Among the more established generations, I would think of Nathaniel Mackey, Susan Howe, Rae Armantrout, Lyn Hejinian. Some of these people you might be more likely to find in The Best American Experimental Poetry. Since the early 1960s, American poetry has been rather polarized in that way. But social and cultural dynamics are almost always more complex than they appear; there are certainly people who are part of an experimental establishment. I wonder how this compares to the situation for Bengali poets.

A: Is lyrical poetry a dead genre?

E: Not at all! That would be like saying that music is dead.

A: We have to worship beauty as an act of resistance. But is it enough? How else a poet can retaliate? I think you are well aware of the situation in India…

E: Somehow I think the answer to your question points to something outside of worship. Even the worship of beauty. Opinions about what—and how—one worships continue to be used to fuel wars all over the world. Certainly in the US, in India, in Israel and Palestine and elsewhere in the Middle East—but also in places like Brazil. Whenever one thing, one idol, whether it is religious or monetary, is used to reward believers and punish nonbelievers, we are in trouble.

So much is called for right now, it is impossible to know where to start. I love what John Cage suggested: “Begin anywhere.” I try to remember that advice every day.

Courtesy of duniyaadaari, our partner site where this important dialog was first published https://duniyaadaari.com/aritra-sanyal-in-conversation-with-elizabeth-willis/

Elizabeth Willis is a poet and literary critic. She currently serves as Professor of Poetry at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She has won several awards for her poetry including the National Poetry Series and the Guggenheim Fellowship. Susan Howe has called Elizabeth Willis “an exceptional poet, one of the most outstanding of her generation.” Elizabeth’s much acclaimed volume of poetry, ‘Alive: New and Selected Poems’ came out in 2015. The book was nominated for 2016 Pulitzer Prize. She was awarded with Pen New England/ L.L.Winship in 2012 for her poem Address. In 1995, her second book of poems, The Human Abstract, published by Penguin got selected for National Poetry Series. As a poet, Willis employs the use of “hybrid genres,” an attempt to “push the limits of representation.” Turneresque, for instance, draws on elements as diverse as the Romantic sublime and film noir. In terms of style, Willis is most often recognized for her “intense lyricism.” Her poetry tends to center on the relationship between art and nature and has been noted for its musicality and precision. Her literary criticism is concerned with 19th century and 20th century poetry and the ways in which changing technology comes to influence the production of poetry. She also investigates the effects of public and private spaces in her prose. Additionally, Pre-Raphaeliteaesthetics and the relationship between contemporary poets and antecedent poets are also frequent concerns of her work. Willis has dedicated a significant portion of her career to a study of the works of Lorine Niedecker.

Aritra Sanyal is a poet, translator, researcher, and an ex-sports journalist who presently works as a teacher of English language in a school in West Bengal, India. He is a doctoral candidate at Assam University focusing on the novels of Amitav Ghosh. Earlier he worked as a research fellow in University of Calcutta under the supervision of Prof Chinmoy Guha in a major research project: Impact of France on the 19th an early 20th Century Bengali Literature. He is the author three books of poetry. Forthcoming is Ekta Bahu Purano Nei (An Old Absence) from Pathak Press, Calcutta.