Introduction to Ludovico Corrao, excerpted Interview: English translations by Gia Marie Amella.

From Gia Marie Amella’s unpublished manuscript of interviews made in Sicily in 1999. All photos, courtesy of Modio Media.

This is an excerpt from a collection of interviews made by Gia Marie Amella between 1998-1999 in Sicily with the support of a Fulbright grant, with an update over two decades later.

Earthquake Mayor

Ludovico Corrao is coolly dressed in a flowing linen tunic. He’s standing on his patio as our car rolls up the driveway somewhere on the outskirts of Alcamo. We’ve been invited to lunch. I note the modern sculpture scattered across the manicured garden that sets off his stuccoed modern home, part Palm Springs, part Casablanca. Shielded from the prying eyes by a tall privacy fence behind which the arid Sicilian hills played peek-a-boo. The whole scene was aesthetic perfection of the highest order.

Corrao had dedicated his life to politics, playing a role in traditional Christian-based parties to ideologically wide-ranging coalitions like the now-defunct The Olive Tree. He’d enrolled in the seminary as a young man, had a change of heart, and switched to law. One of his early cases struck at the core of a predominantly Christian society that still cast women in the role of sexual provocateur— his successful defense of 17-year-old Franca Viola whose ex-fiancé had kidnapped and repeatedly raped her. In the mid-1960s, when Corrao took up Viola’s cause, Italy’s penal code defined rape as a moral offence rather than a criminal one. If a marriage took place, the rapist’s crime went unpunished. Particularly in the South where strict codes of conduct still governed relationships between the sexes as they had for centuries, Viola had dared to defy social convention and became a pariah in her own community. Only in 1981 did the Italian government decree that marriage was no longer a panacea for justifying a rapist’s heinous actions and that rape was a punishable crime.

The cause célèbre sealed Corrao’s political ambitions and he would eventually win a seat in the Sicilian senate. A few years after the Viola case, a sequence of deadly earthquakes rattled across the Belice Valley between January 14-15, 1968, claiming hundreds of lives and leaving some 100,000 people homeless. Across the valley, entire villages had been reduced to rubble and Corrao, elected Gibellina’s mayor the following year, faced the monumental task of rebuilding the lives of his constituents. Relishing a challenge, he wanted to create something totally new, far from Gibellina’s ruins—a city of hope, a city of the future. The new settlement city would fuse function and modern aesthetics: wide promenades and elegant portico-lined squares to create a constant interplay of curves and bold lines, and the ample use of native and Mediterranean white stone for lightness and luminescence. Corrao aimed to elevate the city to a higher purpose through the transformative power of art. Today, Nuova Gibellina is one of the world’s largest outdoor art museums containing works by acclaimed Italian and international artists scattered throughout the city, some created in memory of earthquake victims. Then there’s Alberto Burri’s Il Cretto, (The Crack or The Great Crack), the only work made of concrete built directly at the site of the destroyed village. Presciently, Corrao understood Il Cretto’s potential to bring tourism to the area. Every year, thousands of visitors turn off the Strada Provinciale 5 to wander Burri’s maze of concrete pathways where, just a few meters below, there was once a village full of life.

The senator’s home was just as exquisitely appointed indoors, all glass partitions and teaming with artifacts he’d collected during his travels. Along the length of one wall, hand-painted drapes with a Moorish look cascaded to the floor, like the backdrop of an old movie palace. Lunch meandered through the afternoon. A young Moroccan man served a sumptuous array of courses at a white marble table. He ate with us and, though I admired Corrao’s egalitarian approach, I wondered if there was something more to their relationship. At the head of the table, Corrao effortlessly held forth on an array of topics. When he turned to address me, he listened with genuine interest. Between courses, Corrao’s friend, an author, asked me sotto voce what I thought of our host. I was truly bedazzled by him. Later, over coffee and liquors on the patio, they talked about their plans to create a moving image archive for a planned cultural center and asked if I wanted to help. They had no funding yet. Polite but non-committal, I promised I’d think about it.

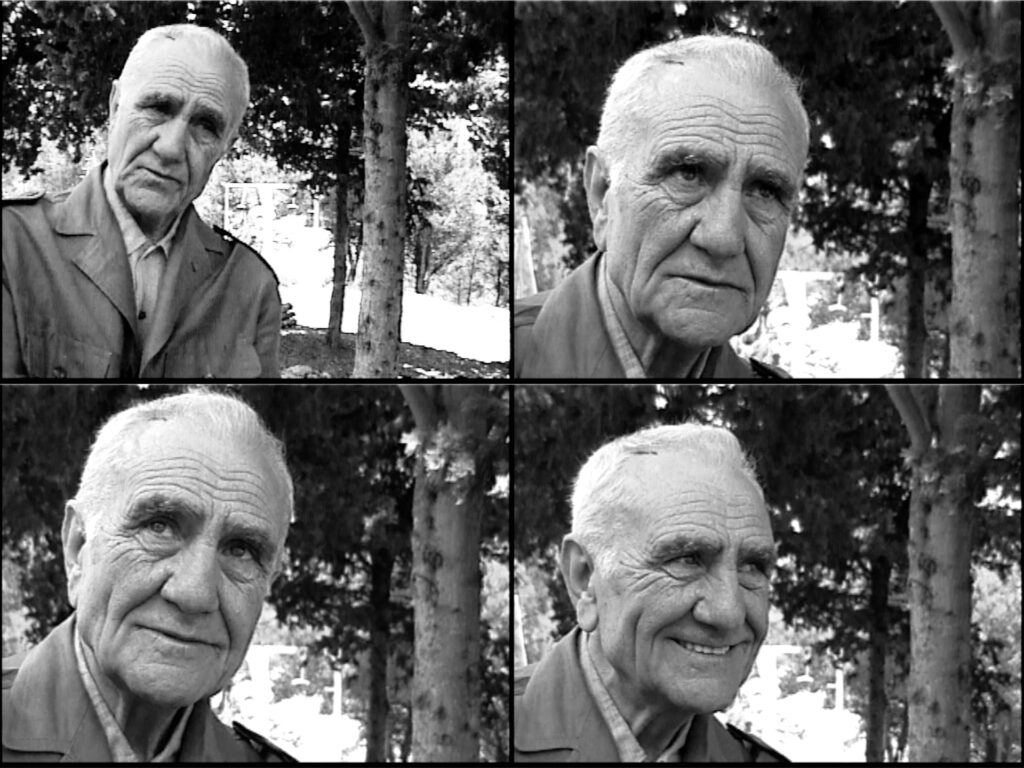

A few weeks later, I was back at Corrao’s home to interview him. He was wearing the same flowing tunic that set off his tanned skin beautifully. He truly was magnificent, like a Roman Senator who’d just stepped out of the Forum after a successful debate. His keen oratory skills propelled the conversation and he frequently used pause to great dramatic effect. He told me about the Sicily of his childhood, his pride in the many cultures that ran through his veins, and rebuilding Gibellina in the quake’s aftermath. He referenced nature a lot. From what I’d seen, he was living in paradise.

We never met again. A few years back, I read that Corrao had been brutally murdered at home. His housekeeper, a 31-year-old Indonesian immigrant, fatally stabbed his employer and immediately after called the police to confess to the crime. The Italian media had a field day, leaking salacious details meant to expose the true nature of their relationship. I was sad that he had died in such a brutal way, and, frankly, I didn’t care to know more about his private affairs. Corrao had brought his community back from a very dark place. His memory, for what he had done in the name of women’s dignity and self-determination, will remain ineffaceable, an illuminated and illuminating spirit under the incandescent Sicilian sun.

Editor’s Note: In October 2024, the Italian Ministry of Culture proclaimed Gibellina as “Italian Capital of Contemporary Art 2026.”

Gia Marie Amella: What do you remember about Gibellina and its reconstruction?

Ludovico Corrao: Total destruction, a war zone. I remember the voices of people who were dying under the rubble and the impossibility of helping them. And I remember the dire circumstances in which they found themselves at that moment, incapable of escaping the law of war and the law of death. I felt compelled to take action, to work with others, and to work with the local population who were prepared to wage a fight against the inevitability of death.

It was a sign of their vitality which is a hallmark of Sicily’s history. If you look at history and at the reconstruction of “earthquake” cities, if you approach rebuilding with a higher aim in mind, you do it through art and culture and by understanding people’s needs, in order to achieve the best outcome for society. This is liberation: transforming the earthquake from a death sentence into a life sentence. And in the order of things, life emerges from death.

We launched an appeal for people of goodwill from across the globe to show their solidarity with the people’s need for rebirth. On the night of the earthquake, people scattered to the four winds in search of salvation. Slowly, they began to return because they believed that their life—their salvation—was exactly where they were born and not somewhere else. That the possibility of rebirth lived within themselves and not outside. There was a desire to seek answers to the rationale for life, the rationale for history, and for a mass movement characterized by Sicilians’ struggle for freedom through the centuries.

GMA: How would you define Sicilian essence?

LC: Sicilians are islanders but they are also beings who have the capacity for universality. Sicilians are isolated beings but they are also akin to devices capable of intercepting all the world’s sounds and, above all, those of the sky and sea. There you go! The Sicilian is a receiving instrument. Sicilians are also the sum of [many] identities. They don’t have their own specific identity and I would also add, fortunately so. In fact, Sicily has never been a nation because it is the fruit of many cultures, the fruit of many identities. This is its true wealth. Each one of us is the bearer of many seeds that produce more fruit, more flowers. Each of us is the custodian of many languages….And our language comprises Ancient Greek, Roman [Latin] and French. It was shaped by the Arabs and the Greeks. Our language has transmigrated to…New York, Brooklyn, Australia. This is a Sicilian. Above all, words, both received and given.

GMA: How would you describe the place of your childhood?

LC: I was definitely shaped by the civilization and the culture from which I emerged. A place of high-quality farmers who developed a great economy with grapevines to produce wine. A place of craftsmen of great intelligence and imagination and of artisans who loved art and culture. Who attended the theater and read Dante Alighieri and the great poets. Who knew novels. The life of a small, though not insular, world that captured the waves of the world.

GMA: Do you have strong recollections of your family?

LC: A very strong memory, memories of my mother. She embroidered and ran an embroidery school so I lived in the midst of these women who embroidered…and who had this poetic ability to transform fabric with thread, with color and texture, and with poetry, [transform] a thought. My mother passed this on to me. My father was a craftsman, a mechanic of consummate skill, who also had the ability to create tools. I remember that during wartime you couldn’t find surgical instruments and my father created them for use in our hospital. Every year, he built my nativity scene with his own hands, the shepherds made with clay or carved from wood. Every evening, he sat me on his lap and read me Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy. He read me old stories and beautiful poems. This is the world that nurtured me. And my parents’ friends were similar, living in dignified poverty that prevented you from knowing about life’s so-called material riches, but that compelled you to discover the depth of feelings every day.

GMA: You lived through World War II. What experience clings most to your memory?

LC: I was a young man in Naples so I experienced the tragedy of war intensely: Nazi-fascist barbarism, the Americans’ arrival, the massacres of Nazis and Fascists. I had to escape from Naples and retreat to Benevento [Campania]. I suffered through the bombings and was saved from the rubble. Then I returned to Sicily, my home, my mother, on foot by makeshift means, and crossed the Strait of Messina by boat. This helped me understand what war is and how terrible it is, but it also taught me to always build words of peace.

GMA: What are your words of peace?

LC: The word of peace is the ability to communicate, to understand others, to assimilate others’ virtues and qualities. Because all human beings are as one. All of us, Creation’s great production. Together, we give to creation what creation gives to us: The ability to navigate and discover together nature’s treasures and secrets, but the sky’s and the universe’s secrets, too. This is humankind’s salient function. And this objective absolutely requires, postulates, the union of people. In other words, a code of coexistence, not merely of tolerance, but of coexistence and cooperation between all peoples.

GMA: Do you believe spirituality exists in Sicily?

LC: Certainly. Sicilians emerged from this constant, unchanging presence of extraordinary light that surrounds and transforms them. And from this sun that stimulates and sulfurous vapors that trigger exhaustion, and chemical elements unleashed from their volcanoes that make them electrified and electrifying. Above all, they are pervaded by all of these inputs of beauty unleashed from every corner of nature and the landscape, as well as from testimonies handed down from diverse cultures and civilizations that deposited the best of their essence here. And it was here that they had the capacity to give something different of themselves. The Greek identity here is different from the original one found in Greece. The Arab identity here is different from Arab identities in their place of origin. Here, everything transforms. Here, there’s continuous metamorphosis.

GMA: Let’s talk about fatalism. Do you think it is a strongly rooted characteristic of Sicilian culture?

LC: Fatalism is a fact of some strata of our society. However, it doesn’t prevent intellectual or creative activity. [Fatalism] is merely the awareness of the immutability of situations and that it can also transmit a sense of profound wisdom. This awareness of the immutability of situations, however, doesn’t place Sicilians in a stance of absolute passivity and inactivity. For example, Leonardo Sciascia is precisely someone who understood the impossibility of things. Yet, he maneuvered with conscience, and with an awareness and strength that things could still change. In other words, hope against all hope. Fatalism has never dominated the Sicilians because the fact remains that Sicilians escaped from this land. They emigrated elsewhere. It’s a sign of a capacity for profound and total recreation. So, it’s not an acceptance of a state of the impossible modification of things. It’s an awareness of the enormous difficulties involved, perhaps also with an element of wisdom. Why at times change or modify? To what end? What’s the outcome of certain accelerations of civilizations with respect to the profound essence of humankind and the spiritual conditions of life? What’s their destiny in 70 or 80 years of life? What changes? What doesn’t change if one remains inert inside the amniotic fluid where one is born and where one might prefer to swim?

GMA: As a Sicilian, you’ve come across reductive and misleading stereotypes. How do you consider them?

LC: There is a stereotype that others construct around Sicilians that they accept out of convenience or laziness. This alone is convenient for non-Sicilians. Sicilians are different from one another. There are many Sicilies, there isn’t just one Sicily, piled on top of each other or even sometimes in contradiction with one another. Accumulated layers, more or less assimilated. But there is no one stereotype of Sicily. For example, if you take into consideration a land like Sicily compared to other areas of Italy or Europe, percentage wise it has produced more artists, more poets, more writers, more musicians, more painters than other geographical regions. So, what is the Sicilian stereotype? Naturally, Sicily coexists with various things, so-called contradictions, but they are vital elements and not stereotypes. In any case, it’s a model of many other situations that exist in the world.

Q: What differences are there between the Sicily of the past and that of the present?

LC: It’s all present. There is no Sicily of the past. The future is everything that we are building on every day and what is stored in our feelings, in our intelligences and our hearts. The future is what the world gives us and our ability to receive what’s being planned for the world of the future. Beyond all else, what’s being planned lay in the world of science.

Q: What must Sicily do in order to preserve its values and traditions?

LC: Sicily needs to observe, reflect and become increasingly aware of its history to orient itself in the present and to move towards its own becoming. Sicily only needs the tools of awareness, above all, tools of communication shared with the entire world. Sicily needs to give the world a signal as to its ancient virtues. Sicily needs to be increasingly included in the contemporary world. To not be isolated or secluded, to not be the solitude and emptiness of its being.

GMA: What potential do you envision for art?

LC: Art must conquer spaces yet have the awareness that it cannot transform the world. It must do this with humility and modesty as a steady, continuous witness and critical part of society. It must have the awareness of being a seed that perhaps may not even germinate today. But like those mysterious seeds that manage to germinate after a very long time, sometimes after being buried in glaciers for millennia, only to come back to life. Art must have this awareness of being the leaven of society.

GMA: Do you see globalization as a threat to identity or as a process that cannot be done without?

LC: Globalization is an effect of human action. And like all human actions, it has destructive capabilities. But then there’s the wisdom of many who know how to transform all of these things into opportunities. Of course, globalization homogenizes and simplifies. Globalization favors the domination of a few over the entire world. It favors the unscrupulous game of finance and wealth but at the same time, it can accelerate modes of communication. Or, it may have within itself the seeds of revolution.

GMA: In what sense do you mean revolution?

LC: Revolution is always the ability to transform the rules of the world, to make them better. What we trivially call progress. But it is called revolution if it also entails the richness of people’s feelings, their freedom. Their need for love and for peace. Their need for conscience and for freedom.

GMA: As the new millennium approaches, I sense that many Sicilians still live on insularity. How do you see this?

LC: Right now, Sicily isn’t in one of its happy phases. It is experiencing the uncertainty of its role and the impossibility of carrying out its function both in a national context and in a European and international context. At the same time, opportunities need to be created so that we can escape from conditions of insularity. The problem becomes one of shattering this shell of traditions that are negative and limiting. The problem is to tune into everything that’s produced in the world today. The problem is to grasp onto aspects of contemporaneity and modernity in the best sense of the word, because modernity is not the superficiality, the comforts or ease of life. To grab a hold of stimuli that come and fight against a system, a culture, and a large part of the dominant society that wants to force Sicily to remain in a state of insularity so that it cannot compete. So, it’s not a matter of Sicilian inaptitude. It’s a matter of the historical, political and economic conditions that tend to keep Sicily in a passive role. While I believe that the world needs all human voices that are able to encourage thought and creativity, this was Sicily’s role and must return to being so. In my small way, I’ve tried to set an example that all of this is possible.

GMA: Among the many cultures that have passed through Sicily, is there one that’s left a strong trace?

LC: Which touches my sensibility, my being, the most? They are all extraordinary, important civilizations. I refer more to the models of Mediterranean civilizations, predominantly Greek and Arab, but attempting to find their traces in all of these civilizations. For example, the Greeks knew how to sift through Middle Eastern and Eastern civilizations and did great work of filtering Egyptian civilization. In turn, Egyptian civilization was the great resource that came from Central Africa. And the Arabs who subsequently assimilated all these things together, and trades that established relationships of structures, signs, and languages from the farthest reaches of China to our lands. Let’s return to the theme of Sicily and this extraordinary intertwining, this extraordinary fabric, these extraordinary cues. Traces that run deep and continually bear fruit.

GMA: A parting thought you’d like to share?

LC: I wish for Sicilians to have the qualities of leaves. The wind shakes them and gives them a start, but they manage to resist and not stumble. Exactly, Sicilians are stones. May they be strong like the leaves attached to their tree and roots and in their capacity to bear fruit. We must all work toward making this wish come true even if we know that perhaps it will not.

A Chicago native, Gia Marie Amella co-founded Modio Media Productions Inc. in 2006, an Emmy-nominated video and television production company whose work has aired on leading news and entertainment networks worldwide. She earned her M.A. in Radio-Television (1993) from San Francisco State University, where she also served as an adjunct lecturer in the Broadcast & Electronic Communication Arts Department, and a B.A. in Italian Literature (1988) from the University of California, Santa Cruz. The recipient of numerous awards for achievements in her field, in 1998 she received a Fulbright Fellowship supporting her research on popular traditions and identity in Sicily, her ancestors’ homeland. Her writing has appeared in Green Living Magazine, Italy Magazine, The Italian American Review, and Cnn.com. She lives in Montevarchi, Tuscany with her life and work partner and rescue cat.