Starting in 2015, Peter Ydeen has been photographing at night in the Easton Pennsylvania area. Beginning with images of George Tice’s elegant night shots in mind, it soon matured into much more than he had expected. Night has It is own visual rules, its own color wheel, and its own ethereal presence. City lighting is meant to light up objects in much the same way you would light a still life or a stage set. He reflects on an unusual night journey through houses, closed shops, strange and common objects, streets and parks – an emotional urban landscape developed with a precise focus.

A talk on the artist’s creation of the sublime and mysterious imaginary seen in his Easton Nights solo show, at the AOC F58 Galleria Bruno Lisi, in Rome.

Camilla Boemio: Which artists have influenced you the most at the beginning of your career?

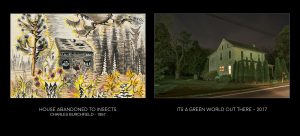

Peter Ydeen: I became immersed in photography around 2104 after many years of involvement with other aspects of art. My initial fine art training was in sculpture and painting. Painting was taught by going outdoors in the Virginia mountains and painting landscapes from nature. Because of that, my major influences in the beginning were the American Modernists such as Marsden Hartley, Charles Scheeler and especially Arthur Dove. Paul Klee was also someone I spent a great deal of time looking at and I find the Dadaist have been a major influence, both in appreciation of the mundane as well as the occasional levity which sneaks into my photography. My main professor, the painter Ray Kass, would often mention the American painter Charles Burchfield, in that my landscape painting was similarly stylized. Though Burchfield is never someone I emulated, his work has always been on my mind, and since moving into photography, I believe he is the single most influential artist for my current work. This is both because of the similar subject matter, small town urban landscape, but even more because his work always attempted to show more than the visual. I believe this sort of sixth sense is key to my photographs.

In my beginnings as a photographer, and especially night photography, George Tice was really the only well known photographer I looked at. Although he only occasionally did night photography, his photograph of Petit’s Mobil Station is the single most important shot with regards to my own work, and possibly the most important photograph to the other contemporary night urban landscape photographers as well. As I continue in night photography, I find Robert Adams as being very important both because of his series “Summer Nights” but also for his ability to put urban landscape into words. He also is an interesting example of how the night’s own aesthetics can change those of the photographer. bringing the New Topographic photography back towards the pictorial.

I have had a lifetime touching on many different areas of fine art. They all have contributed to my learning to see. The time spent outside of myself and handling different types of art on a daily basis, often by unknown artists, comes through in anything I do including my photographs. People like my wife Mei li, who introduced me to West African and Chinese art, and Marc Leo Felix, the great scholar on Congolese art who taught me much about African sculpture, were both key in my everyday vision. Running a gallery selling Chinese, Tibetan and African art, though in a roundabout way, helped refine my vision in making my own art and so I feel it needs to be mentioned here.

Photo by Charles Burchfield, for comparison.

C.B.: Do you feel any influences from other expressive forms such as literature or cinema?

P.Y.: In my early years studying art, I took a course in Romantic Literature, which included readings of E. T. A. Hoffman and George MacDonald. I cited the work of those two authors for my masters thesis show many years ago, referring to how their work created worlds which brought people inside as a way of engaging the audience. I believe this is one of the reasons night photography resonates with me so well. It takes you away from the flat surface and brings you inside. Though my photographs are not a created world such as Hoffman and MacDonald, and are certainly not escapist. They draw the viewer inside to see not another world, but our own world in a different light. It is more of a unique reflection creating metaphors for our everyday landscape.

Every object becomes more than it seems in our daily lives, much in the same way Duchamp elevated a urinal to fine art.

With regards to cinema, I believe the night landscape presents itself in cinematic terms, and dictates to some extent that aesthetic. Robert Adams series “Summer Nights” is full of that cinematic expression, the source however is not Adams himself, but the night. When compared to his other urban landscape photography, it becomes obvious the source of the cinematic effects is the night itself and not the person. Though I believe cinema has influence on my work, especially people like Guillermo del Toro, I still think it is more that cinema naturally mimics the night landscape and how that resonates with me.

C.B.: You have also worked in film making, how have drama and mystery developed your imagination?

P.Y.: In my 20’s I worked freelance in a variety of fields which included all types of technical work, such as technical drawings for lighting designers, model sets for movies and film, drafting for industrial show designers, some set building, and some model and prop making for photo ads and a great deal of architectural model making. I also had a number of friends involved with staging and so I was constantly around people involved with that field. So I would say the influence of cinema and film on my work was more of an osmosis than a direct borrowing. The most important aspect was probably a sensitivity to theatrical lighting. That said, my photographs are not invented, but show a place that is really there. The drama and mystery are natural to the night. The use of my imagination is very different than when I make a sculpture or painting. Instead of creating this drama and mystery from my imagination, I feel it is more presenting and clarifying the natural drama and mystery of our places and how it is revealed at night.

C. B.: In what ways have architecture, landscape, the city and urban geography become relevant for your research?

P.Y.: I have always had a fondness of architecture. My brother is an architect, as well as my best friend. I did a great deal of work as an architectural model maker during my 20’s which allowed me to work on designs of the greats like Emilio Ambasz, Phillip Johnson, Michael Graves and many others. To this day, every city building and wall looks like a model to me. It helped to install a sculptural sensibility to my vision of the urban landscape. I also studied sculpture in college, and so together with the work with architects, I developed a fondness for shape, volume and the arrangement of space. This is core to many of my photographs, as the whole of Easton Nights is a presentation of our spaces. My early day photographs were often the backs of malls, and spaces where you get a very pure geometry. Though the night added a third dimension to the photographs, I still look for spatial relationships and how light plays with the geometry in many of my photos. I would also mention my early hand drafting done for architects and technical illustrations, both in school and professionally, also installed a liking of perspective which comes out in the many angles and vanishing points in the photos. My studies of pure landscape painting was also important in that it gave me a good sense of interactions of colors and patterns which I can often see in urban landscape as well. I also do a good deal of photographs which include trees, bushes and other elements of traditional landscape painting.

From the Easton Night Series

Peter Ydeen, Six Hitches, Easton Nights Series, archival print on Canson Bartya paper, 2017, Courtesy the artist.

Peter Ydeen, Diner Through the Trees, Easton Nights series, archival print on Canson Bartya paper, 2019, Courtesy the artist.

Peter Ydeen, Garden of Easton, Easton Nights, 2017, Courtesy the artist.

C.B. How did the project Easton Nights evolve over time?

P.Y.: Easton Nights was not a planned series, and evolved naturally over the last several years. The first few shots were actually black and white as I was looking at George Tice’s work. One of the first changes came as I felt the night worked with its own color wheel. The light sources are all mixtures of artificial lights as opposed to daylight. This combines with the difference of a camera which sees color in the dark, as opposed to the human eye, whose vision goes towards black and white at night, as the cones lose function as light dims. And so the first development was from black and white to color and a fascination with that color. The other change that happened in the beginning was the move away from my daytime landscape photography which often emphasized a flattened geometry and the arrangement and interaction of shapes to the night which is naturally attuned to depth. This was a very strong attraction to me. And so in the first several months of shooting, i found myself turning towards this sense of depth and drawing the viewer inside. The last major change was that in the beginning I did little to process the original shot, and so the work was much more ambiguous and moody. As time went on, I started to find ways to bring out the shadows, and my post-processing was all done to bring clarity to the image. Some of the mood went away in exchange for a much richer image with the shadows having definition and life. That is still where I am at with the series.

C.B.: What about the power of one photograph?

P.Y.: Many photographers as well as their series are remembered by single photos. With Eggleston for instance; I immediately think of his “Memphis” photograph of the “Tricycle”. Obviously single images can tell a story by themselves, but I believe that with Easton Nights the strength is in the entire series and not in specific images. The most well know of the series is “Pink Line”, but this is also one of the least typical. The images seen together play off each other creating a bigger story, while isolating an image seems to stop that conversation they have with each other.

When I give talks about my work, I divide the photos into different aspects of night photography. One section I call Mimesis, which means the imitation of life in art. These are photographs which seem to tell a story by themselves away from the series, and are photos which I feel are also my most successful. Mimesis could also be renamed Metaphor. Though I consider these photographs the most successful, and also they are the most popular, they still do not have the power of the whole series together and tell a story in a more singular way.

C.B.: For David LaChapelle: “Real artists take chances and risks and they don’t worry about the repercussions.” What do you think of that?

P.Y.: The statement brings up a good point, though sounds a bit macho. When artists create work, they present their whole “self “ for everyone to see, and a good artist to a greater degree may have an audience of one or of millions, but it is that risk that takes courage and even more so to persevere through criticism and negative feedback. And so I think every good artist takes risks, though it may not be so evident, seem so innovative, and might not be a defining point for others. It is still chance taking. It is helpful for an artist to understand rejection and what some take as failure, can be their best friend as it keeps you changing. Many financially successful artists make one great statement early in their career, but then continue to always just repeat it, possibly because it pays the mortgage or sends their kids to college. These artists can be less creative than their accountant. Creativity requires change and movement and following your instincts despite what others may say. It is all a continual risk but what “taking a chance” is depends on each person.

C.B.: The discussion of the intersection of photography and painting is an old masterful argument. Around the beginning of the decade, this debate reared its head in earnest through the attempts of artist such as Gursky to create photographic works that would match painting – particularly that of the 18th and 19th century – in both scale and allegorical heft (using elaborate, cinematic staging techniques and digital illusion). You came from the study of art history, what do you think?

P.Y.: So much is semantics and can depend on different people’s definition of painting and photography, but to me they are two vastly different things, each with its positive points, and each with its limitations. People often unintentionally refer to my photographs in my exhibits as paintings. I can see people identifying my own work with the 19th/20th century Pictorial photographers, such as the first night photographers, Stieglitz and Steichen, who were involved in this comparison between photography and painting. This intersection of paintings and photography by these artists is my opinion occurring only in the overall aesthetics. It is only evident from far away or on a monitor not when you have the pieces in front of you. A painting is a tactile object, and inseparable from its method of construction; an intuitive construction of marks; its overall presence being inseparable from the laying of the paint on the surface. In my opinion, I would say that with smaller works like mine, and that of the pictorial photographers, it is just that, an ‘intersection”.

Gursky is a different matter. The ways in which he “intersects” painting is in a whole other place than myself or the Pictorialists. The large size command a space in a similar way to large paintings, but again only from a distance. They also have that similar cinematic presence and the allegorical subjective quality you mention. But still when you get close, they are completely different objects, with the painting going back to the paint, and the photograph to its sense of the moment and depth of detail.

If I was to select a photographer whose work is most like painting, it would be someone like Brenton Hamilton, whose cyanotypes have that sensuous tactile feel to them. You can feel the hand being involved in the creation of the image, much like the creation of a painting.

C.B.: Are we living in ‘photography after photography’ times?

I believe so. Both Digital photography as well as the new and different technologies for analog photography take such an alternate approach to the traditional analog photography that I believe there is a necessity for a new categorization. Although there is always the intersect you talked of as well as a sharing of terms, It is difficult to compare the new and old because of all these new variables. The digital darkroom or post processing methods are much more vast and immediate. While the analog darkroom involves the actual touching of the material while it is being created, digital photography allows for the introduction of new elements, such as color and tone, as well as pure invention, duplication, and a slew of other techniques which are totally unavailable to traditional darkroom post production. I wouldn’t term this as good or bad, but different, and it produces a different end, making it worthy of distinguishing definitions between the old and new.

C.B.: What are your plans for the near future?

P.Y.: I am always swimming in plans and always more than I can realize. I have just finished organizing my studio and begun doing some still life photographs in connection with some previous box sculpture I had done. It is very different than the night urban landscape work. I will still be going out regularly to do the night photography, but for a while at least, I plan on changing my focus. I will still be arranging more exhibits of Easton Nights, and I am working on a nonprofit status which would allow me to fund a long overdue and very thick book for the series. Lastly I will be working on finding marketing for my work. I have concentrated on exhibitions at colleges and nonprofit institutions and need to now also address the more practical end of selling work. I always have a need to make things, but I approach the future in an undogmatic way. Plans get me going, but the only thing for sure is that I will keep making something. Whether it is photography, sculpture, painting or a combination of the three, I am not sure, but there will be something new soon.

Photogallery contents:

- Peter Ydeen, It’s a Nice Night for a Picnic, 2016, Easton Nights series. Courtesy the artist.

2. A Boat near the Olde Town Motel, Easton Nights series, Courtesy the artist.

3. Bush Shadow, Easton Nights serie, Courtesy the artist.

4. El Camino with a Cap, Easton Nights, Courtesy the artist.

5. Night Bush, 2016, Easton Nights serie, Courtesy the artist.

6. Pink Line, 2017, Easton Nights, Courtesy the artist.

7. The Gate, 2019, Easton Nights, Courtesy the artist.

Comments 1