The eighteen years I lived in the Amazon, fighting alongside with and for the indigenous people in the defense of their rights, lead me now to walk the paths of the Internet on a daily basis. I am always searching for good news that will, at least partly, alleviate my bitterness for being, currently, so far away geographically from Brazil. I consider myself an indigenist and a writer, so literature is the subject of my research and reflections as well.

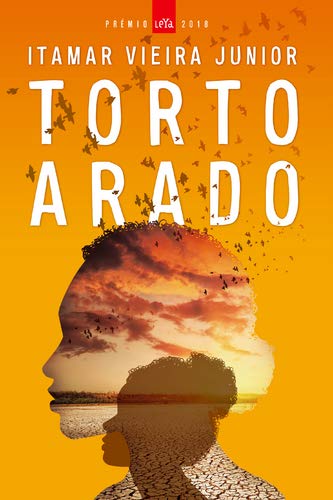

In June 2020, I was greatly intrigued by the news that the Brazilian writer and activist Itamar Vieira had won the prestigious LeYa-2018 Literary Prize in Portugal for a still unpublished novel Torto Arado (Crooked Plow) and that spurred me to find out more. The information I cobbled together about him brought him closer to my heart because of our many shared experiences: we read a number of the same authors, as teenagers we wrote in secret from our families, we studied the thought of some of the same anthropologists, we were both involved in the struggle for land waged by the poorest segments of the Brazilian population, neither of us were ever seriously taken into consideration by prominent publishers because of our working-class backgrounds and the issues we deal with in our work. Itamar Viera’s life path triggered me to ponder, be aware and hope. With this brief essay I would like to pay homage and thank him.

Itamar Vieira was born in 1979 in Salvador, in the state of Bahia, Brazil. His identity alone as a nordestino* made him a target of discrimination. In addition, his ancestors included black slaves, indigenous tupinanbá, poverty-stricken Portuguese immigrants. He was born and lived in the city of Salvador, but his father and paternal grandparents worked in the countryside; that is why his childhood memories are firmly tied to peasant culture. He was trained as a geographer thanks to the “Milton Santos” scholarship awarded to low-income young blacks, and he was the first student to receive it. He participated in some national job competitions hoping to become a teacher but in the same period he also applied to INCRA (the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform ) finally choosing to work there, as he believed it would more challenging and stimulating for him than to implement his concepts in schools. Upon leaving his native city of Salvador, Itamar entered what is known as Deep Brazil. There communities do not struggle to live but merely to survive; slavery, servility, racism, male chauvinism, discrimination, violence, injustice are rampant; land conflicts are brutal and constant. The real wealth of Deep Brazil consists of the cultural diversification of its population, the solidarity of which such population is capable, their formidable resistance to the abuses of local oligarchies and the State.

For fifteen years, through the INCRA, Itamar developed peasant literacy projects, documented the rural work performed by women, worked for land regularization. In 2017, he became a Doctor of Ethnic and African Studies with a thesis on the formation of Quilombolas ** communities in the Brazilian Northeast. His experiences and his encounter with indigenous people, landless workers and quilombolas gave rise to most of the characters in his books. He has given voice to a slice of humanity that has been mute for centuries, whose existence is suffering and precarious, but whose feelings such as the longing for a dignified life, autonomy, freedom are universal. By mixing real facts with magical and spiritual elements, Itamar has developed a distinct literary style that allows readers to immediately recognize him as the author.

Here are some data recorded by the Study Group in Contemporary Brazilian Literature of the University of Brasilia: 97.5% of Brazilian novelists, published between 2005 and 2014 by large publishing houses, are white, despite the fact that whites are only 47.73% of the population. More than 70% of these writers are men, despite the fact that most Brazilians are women, that is 51.6%. Because they are written by rich white men from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, nearly 78% of the characters in the novels are white and most of them are men. Itamar Vieira did not send the manuscript of his book Torto arado to large publishing houses, because he knew perfectly well what kind of reception they would give to someone like him, an author without connections, of his social background, with his skin color, who insisted on creating such humble and mistreated characters. He sent the manuscript to Portugal instead where it won the LeYa-2018 Literary Prize for Best Novel. Of course, from that moment on, you can surmise that it was the publishing houses who were seeking out the writer… .. In 2020 the book even won the Jabuti Prize, which is the most coveted and prestigious in Brazil.

I end this brief essay by congratulating the publisher Tuga Edizioni, which translated and published the book in Italy. I conclude with the hope that Itamar Vieira’s trajectory will contribute to making most of the medium and large publishing houses, both Brazilian and Italian, question their publishing choices. By continuing to privilege a caste of writers and their ethnocentric interests, they themselves are guilty of discrimination against authors, characters and contents, all of which if included could instead transform the dictatorship of literature into a multi-ethnic, democratic, just, fascinating republic.

Loretta Emiri lived in the Brazilian Amazon for eighteen years, working with and for indigenous peoples including the Yanomami. She has published the Dicionário Yãnomamè-Português, the poetic collection Mulher entre três culturas, the ethno-photographic book Yanomami para brasileiro ver. In Italian, she wrote Amazzonia portatile (Portable Amazon), Amazzone in tempo reale (Amazon in real time, special jury prize for Nonfiction “Franz Kafka prize Italy 2013”), A passo di tartaruga -(At a Turtle’s Pace)In May 2018 she was awarded the special career prize “Novella Torregiani – For Literature and Figurative Arts”. In 2020 her book Mosaico indigeno(Indigenous Mosaic) was released by Multimage press.

Glossary

*Nordestinos = individuals coming from the Northeast region of Brazil.

** Quilombolas = descendants of communities founded by African slaves who fled from the plantations where they were prisoners at the time of slavery. The word quilombo means settlement in the Angolan Bantu language.