NARRATION

He hollered

She slapped

He chose back of the hand

She found the horse whip

I visited the steer’s

rotting carcass

in the sun-blasted clearing

deep in the woods

He threw you out of the car

She brought soap to wash your mouth

He made you write

five hundred times

I won’t ever, I won’t

Buzzards, flies, wasps

by late summer the drying skin

rippling back–bed covers

shrugged off in the heat

She said you’re becoming

one of those

He still had his war

she her grand lost life

Curved horns, shiny hooves, his body

splayed in that galloping pose

daily visit to death, taking in its smell

smell–memory’s cup bearer

When she said pack up

and leave forever

he stared out the window

smirking at blue jays

Honeysuckle, pine boughs,

wild roses, they soften the stench

I’m here

you’re not

I’ve stories to tell

I’ve hardly begun

MANY FAMILIES HAVE ONE

He died yesterday.

I prowl memory’s rooms for his blank

and composed face, dark hair oiled back,

his perfect navy jacket, brass buttoned.

He was authoritative about boats, golf clubs,

tennis rackets, flying first class. You wonder

why I bother to mention him. He did bad things

to many children—not me—and everyone knew this.

Still, he was invited to sit at the table,

encouraged to carry on about luxury watches,

about the best caviar, the finest ski poles,

excellent tires, how to insist on good service.

He was a relation, was considered family,

always welcome for holidays. We kids remained

enraged about him, for years, our grand prince of nothing,

long before I knew the phrase, “banality of evil,” and his

showing up at holiday, all tawdry glamor, and now

he’s dead, far off, finally dead, not missed,

but held strangely in memory, the way you long remember

a bad dream you never entirely waken from.

EARLY EDUCATION

Dear ladies, gents, won’t make it

to your 50th. One day, dear little thugs of long ago,

I arrived in polished boots, fringed shirt

with silver snaps—gift from Ma—and was late,

Dad’s pickup raced us from farm

to town, and I stood before you all—

with your circle pins, pastel flats, your

slicked-back boy hair, penny loafers—

snickering beneath the yellow-toothed grin

of your homeroom goon, Mrs.

Something—who cares! She got Dad

to remove me! Me—bereft of a skirt!

Pa heads us to the track, the late set

galloping out, jogging back. Trainers mumble,

pony girls rosy, hot-walkers, racing forms rattle,

Dad pleased the colt worked the six in twelve

and change, galloped out kindly,

whole backstretch alive

with glazed donuts, cocoa, enough smart talk

to call back, all down the years. World’s had

its way, good times outweigh the rest.

MOM’S LOADED TODAY

Her house got robbed while she slept and her dogs,

her cat, all quiet, all loafing on the job.

Next day off she’s off to the local gun shop,

a grandkid in tow, grandkid’s ma. Little, skinny,

old, beautiful, and so full of herself, Mom wants

and gets the thing itself, and loads it up.

Shows up for lunch at the mall, at the slightly fancy,

Chinese chain place with the requisite, antiquish

rearing and snorting, robust plaster horses out front.

Anyhow, everyone’s ordering up the shrimp,

the sautéed this, the fried that, plenty of sizzle.

She hauls it out, yes she does, dips into her

Queen Elizabeth-era big leather bag and hauls out

the big gun, flourishes it while the waiters scurry,

voices beside her: Ma, shut the hell up, put it away,

and there she was, as we well remember her, waving it,

proclaiming, Ha, I’ll get the stupid bugger next time.

CHESTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA

There were real roads and the other roads, meaning asphalt, meaning they went to nameable

towns; but real roads, meaning dirt roads, shouldered the banks of the poplar-shaded river;

veered along fields with red cattle grazing knee-deep; sliced through corn rows, past the stone

house that collapsed after old missus so-and-so went mad and old mister so-and-so drank himself

into a final tizzy after his best kid was felled by gunshot, though we’ve forgotten which

happened first, but that it did happen, because a man told our dad, who told us about it all

summer, driving to the track at dawn, while cluing us in to everything else we had to know for

later on, always taking the long-cut for the hell of it; but nowadays a dirt road often dies straight

into asphalt, trading the spit and sizzle of small pebbles for the smooth-shaven, high-pitched

sound of fast tires under people in a hurry; although some dirt roads rescue themselves, ducking

into the thickest woods they can find, circling a clearing of charred wood and bent beer cans; and

these are great roads, being neither easy nor soft, but flat-out refusing to be metaphor roads, and,

if you’re lucky, you ride a horse on a loose rein, take the pickup if you’ve got four-wheel.

MELVILLIAN

Almost my favorite lines

during the whole Melvillian winter of hearing him,

not him exactly, but some guy reading him aloud,

mile after mile, and he really did Ishmael justice,

on our long drives home from the valley,

where my favorite lines came at the end

of that interminable chapter on cetological systems,

the nomenclature of whale conformation,

every corner and cranny delved most thoroughly,

as we drove home day after day, the voice instructing

through the long sea voyage, while we lived

through a nearly biblical drought, the air outside yellow,

the winter hills brown when they should have blazed forth

in tourmaline, the sun a sullen, muted lump.

We wondered about him, our guide, not just our reader,

but Ishmael, our faithful teacher, winding down

from the sperms, the killers, the humpbacks,

the tail fin, the baleen, the quality of oils, and he saying,

God keep me from completing anything. And then he saying—

or what we heard him say,

that long drive home from the valley—was that this is a draft

of a draft. But once home and delving the pages, I see

it’s spelled draught of a draught, before flipping

the pages to learn it’s a variant of draft. And so then,

apprised of the tenuous nature of language, I’ve inhaled

the flavor, taken in the draught, the whole measure,

the full scent of his words.

Mom’s Loaded Today– first appeared in Spillway

Melvillian–was published in Euphony

Chester County, Pennsylvania–first published in Sweet: A Literary Confection

Helen Wickes is the author of four books of poetry: In Search of Landscape, Sixteen Rivers Press, 2007; Moon over Zabriskie and Dowser’s Apprentice, both from Glass Lyre Press, 2014; World as You Left It, Sixteen Rivers Press, 2015. She grew up on a farm in Pennsylvania, has lived in Oakland, California for many years, and used to work as a psychotherapist. The six poems in The Dream Machine are from her unpublished manuscript, “Transit of Mercury.” She is a member of Sixteen Rivers Press, which will publish the anthology America, I Call Your Name: Poems of Resistance and Resilience in fall of 2018.

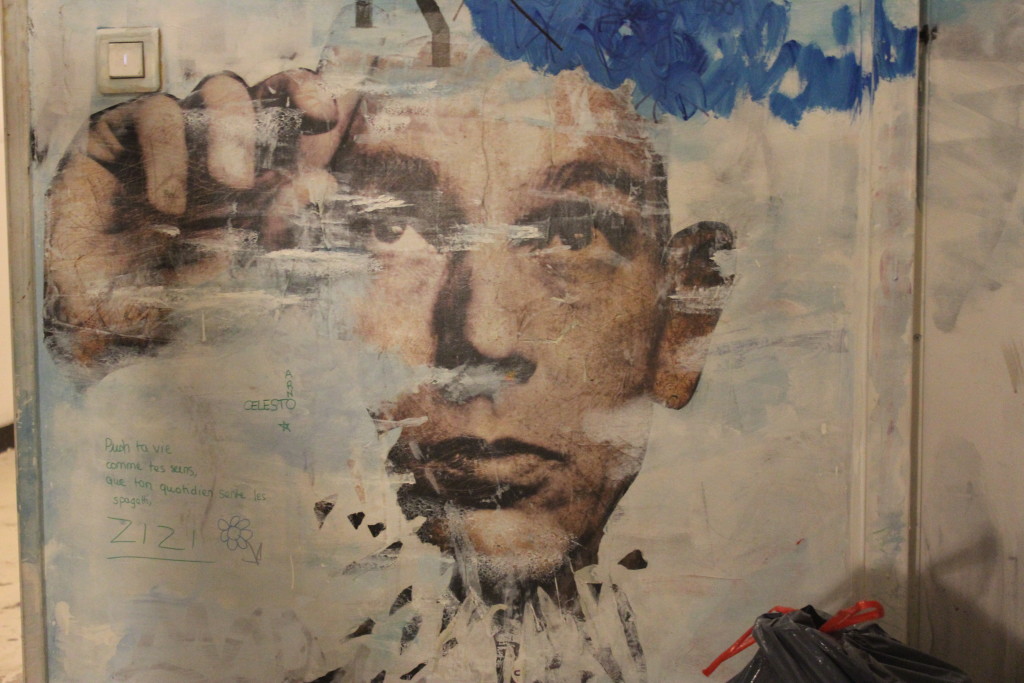

Featured image: Photo by Melina Piccolo.