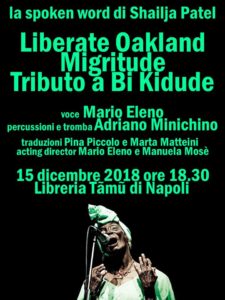

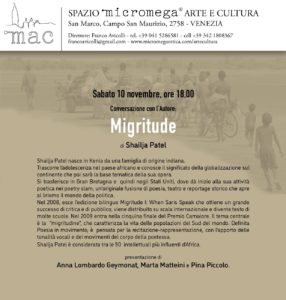

On November 10, 2018 an event with Shailja Patel was held at Micromega Arte e Cultura in Venice (Italy) to mark the ten year anniversary of the release of the book. Actor/director Mario Eleno will perform an evening of readings from Shailja Patel’s work, translated into Italian on December 15, in Naples, at Libreria Tamu, and at San Polo dei Cavalieri (Rome) on December 22, see posters at the end of this article for more information about upcoming events.

Introduzione

Shailja Patel’s latest work Migritude combines in its title the word migrant with the word ‘attitude”, which in the U.S., over the past fifteen years, has lost its neutral connotation of demeanor and has taken on the meaning of pride, rebellion, and an unwillingness to take a subaltern stance. This coined word also retains distant echoes of Leopold Senghor’s concept of Negritude and perhaps brings it into the 21st century, continu- ing the trail of its spirit of pride.

Divided into 17 fragments, this first movement of Migritude is uni- fied by the Sari, a prop laden with layers of meaning. In the stage ver- sion, 16 saris taken from the trousseau a resigned mother has shipped to her stubborn, marriage averse “modern” daughter are unfolded in sequences that underscore the tension between parental expectations and the ambitions of the obstinate, untraditional daughter who insists on being an artist. The girl’s voice is heard expounding an unabashedly feminist/”migrantist” point of view in a dialectical alternation with her feisty mother, whose voice comes through strong, especially in 4 letters. In this first movement, in fact, it is the figure of the Mother that looms large “in all her “wounded magnificence”. The forthcoming movements also draw on the concept of the “first 4 gods” that a Hindu child learns about and will include a second book on the Father; a third one on the Teacher; and a final one the Guest.

In this first movement, over the course of 17 poetic vignettes Shailja Patel presents the audience with a meditation about processes of colonialism and post colonialism, especially as they unfolded in Kenya, her native land. She dissects these processes at a historical and psy- chological level, interspersing her own family stories with testimonies of Masaai women, and shedding light on how it impacts migrant folks over four continents Africa, Europe, Asia and North America.

Shailja Patel develops her own brand of fusion between poetry, theater, historical reportage, opening up lyricism to the world of politics, economics (particularly in the piece Shilling Love), language (in the poem Dreaming in Gujurati) and ending with a kind of “reconciliation” piece in which the daughter summons the mother’s complicity in recognizing the law into which they were born, a law that decrees that for the migrant words don’t come easily, “before you claim a word, you steep it / in terror and shit / in hope and joy and grief / in labor endurance vision costed out / in decades of your life / you have to sweat and curse it / pray and keen it / crawl and bleed it / with the very marrow / of your bones / you have to earn / its / meaning.”

Whether performed on the stage with an Indian dancer as coun- terpart and the visual aid of photographs and textiles, or simply read on the page, Shailja Patel’s strong background in spoken word poetry, honed through her assiduous participation in the 90’s in poetry slams (in which she won many awards) is clearly discernible. All over the United States, in the 90’s the canon of poetry prevailing in academia was chal- lenged, as voices previously left out, especially those of ethnic minorities, demanded to be heard not only as far as content but also in their own expressive forms, which featured a whole range of modes from hip-hop, to performance poetry, to jazz.. Sonia Sanchez, the godmother of perform- ance poetry, in her preface to an important book on poetry jams, refers to the process of ‘jazzing up” the poetic word, “… when they heard some of us read, they saw us look at the word and jazz it up, look backwards at the word and decide to disconnect and reconnect it at the end, stretch it, moan it, groan it, peel it and then finally redress the world and say ‘see this is a poem’.”1

In the piece The making/ Migrant song/ Sound the alarm, this process of splicing is exactly what happens: The Making section reflects lyrically the poet’s consideration about her craft which harkens back to the Greek notion of poetry not as inspiration but as Poiesis, a kind of mak- ing, creation. In Shailja Patel’s case she makes her poetry using as raw materials the experiences of migrants, firstly her mother (not the one she longs for, but the one she has got) and her father (his calloused hands). From these family departure points, particularly her father’s hands, she launches on a whole consideration on hands through the history of colo- nialism, evoking the ghosts of the hands cut by Belgian colonialists in the Congo during King Leopold reign, the ones cuts off from the Arawaks by Colombo, the finger cut off from Indian textile workers to protect the British textile trade. This connects it back to the first piece titled Ambi- Paisley which traces the history and transformation of that design on a world wide scale. She then “splices” these more lyrical materials with snippets of conversation or prose pieces featuring the self-assuredness of locals versus the tentative, ingratiating demeanor of the migrants, who are never quite at ease and struggle for acceptance. The “attitude” com- ponent of Migritude is particularly strong in these fragments as Shailja Patel denounces how the unacknowledged feelings of superiority of the European/American lead them to misinterpret the migrant’s attempts at retaining their identity and dignity (sharing and hospitality, for example) or their contingent circumstances (living in crowded quarters or parsi- mony).

The strength, vitality of Shailja Patel’s poetry and the clarity of her worldview strongly contribute to the efforts of presenting the world of the so-called “Other” in a way that is immune from what Edward Said called Orientalism. Even the richest textured lines and images she bequeaths her readers/audience in the final part of her work, i.e., the daughter’s gift of reconciliation to the mother, her poetry as “… a ship of glittering songs to sail your jewels in./Staking a masthead of verbs to fly your saris from!/ This work which filigrees and inlays all your legacies” clearly belong to the imagination of a 21 century voice for justice that is building bridges and belongs to the whole world.

Pina Piccolo

1. Tony Medina and Louis Reyes Rivera, editors bum rush the page a def poetry jam, Three rivers press: New York, 2001, page XV.

Previous posts in The Dreaming Machine on Shailja Patel:

Issue N. 1 Syllabus Note

Issue N. 1 SHAILJA PATEL ON HOW THE EMPIRE TRAVELS BACK – Bani Amor interviews Shailja Patel

Event in Venice on 10 November, 2018 http://www.lamacchinasognante.com/shailja-patel-a-venezia-sabato-10-novembre-alle-18-a-micromega-arte-e-cultura-mac/