LETIZIA BATTAGLIA

PALERMO 08/06/1999

Q: Letizia, how would you define the essence of sicilianità, of being Sicilian?

When I think of Sicily, I think of this sky. I think of this sea. I think of all of the destruction that took place in the past and over my lifetime. Sicily is a mixture of things: sun, sea, passion, cunning and wickedness and betrayal. Sicily’s a hodgepodge of terrible contradictions. Often ignoble, often sublime.

Q: What do you mean by contradictions?

I’ve personally experienced cunning and betrayal the hard way. Because my people — my people — betrayed themselves. Sicilians were betrayed and betrayed others. They’ve been cunning. And they’ve suffered from the cunning of others. Why? We’re a little bit Arab, a little bit Byzantine. We’re hybrids. We’re not like the British who are reserved or other populations that have a set way of living, that is, with rules. Sicilians break the rules. You can’t trust a Sicilian. Then again, there are Sicilians who are splendid, truly splendid.

Q: Do you believe there’s what you’d call a specific Sicilian identity?

My daughters and I have issues because we have different identities. How can you say there’s only one identity? Who comes to mind? Salvo Lima, Giovanni Falcone? They were different people. One worked for evil and one worked for good. Both were Sicilians. Maybe Falcone, who died a hero, had his shrewd, ignoble things and beautiful things. I don’t know if Salvo Lima had beautiful things. Maybe not.

When I’m on the road, I always want to return to Sicily. Always. I got desperate once. Desperate because I had my own private worries. And I went to Greenland. I put a lot of distance between me and Palermo. After eight days there, I wanted to return home. I always want to go back to Palermo. Why? For the sky, the sea, the light, and for the betrayal. I want to return because life’s an adventure. Sicilians are an adventure. Often terrible, often beautiful.

What do we have in particular? A bit of rational intelligence. I see this. Sometimes, it turns into cunning and becomes something horrible. When I travel far from Sicily, I feel Sicilian. But I also feel that I’m fine out in the world, that I’m fine when I’m in others’ company. I’m Sicilian. What does that mean? It means a lot of good and bad things. We’re certainly different from the Lombards. Maybe we’re a little smarter. I detest cunning. There is cunning out there. There’s something out there that’s not working for society’s betterment. We’re not united. Everyone has an intelligence that she or he wants to impose on across social classes. I understand those people. And to understand them means I’ve learned the rules of the game.

How can I really say what we’re like? I can tell you what I’m like. I don’t want to give up. I don’t want to resign myself to the negative things that we have and you know it what I’m talking about. I just don’t give up. I want to resist with a smile, with joy, experiencing the beautiful things of this land and the world beyond. I’m stubborn, resistant. I do a lot of things so that the many messages emanating from this island are not only those of mafia. Which exists and still controls us. What am I like? I’m a sincere person who’s always fought for justice. Always.

Q: How would you define as sacred? And profane?

What’s sacred? For Sicilians, it’s lot of nonsense. I don’t find that there’s anything sacred here. I don’t believe in the sacredness of things. Honor was once sacred. Honor once meant what was between a woman’s legs. Nowadays, a little less so because women are fighting against this. What’s sacred? Women’s honor. Keeping one’s word is sacred. (pauses) That’s not true. People don’t keep their word. They often break it. Just like everywhere else these days, money is sacred. Consumerism has gotten ahold of us. The Sicilians have been taken in by the most vulgar, uninformed, immature and thoughtless consumerism. They want what everyone else has. I don’t really care what Sicilians consider sacred. What do Sicilians think of as profane? I don’t understand this sacred and profane. My whole life I’ve fought for things not to be sacred or profane. That they stood for life. For respect and justice. Myths don’t interest me. I’m not the right person to give you an answer on what sacred and profane mean.

Q: What does it mean to be a woman in Sicily?

That you’re attractive to men. That men like you. That men really appreciate women in Sicily. And when it’s time for love, they love you a lot. They’re crazy. Sicilians also kill for love. They shoot for it. Today, it means something a little different. Women have always been servile to men in Sicily. Their servants. Even if they were noblewomen who didn’t serve men sexually. Their word was worth less than a man’s. Today, young and older women are rising up and making inroads even though there’s a lack of work. There’s no work here. For women, there’s even less. If they have economic independence they can manage their lives better. What does it mean to be a woman? To always fight. To always stand up against fake loves, fake passions. And to fight to have control over one’s life. I’m a woman who’s always done exactly what she’s wanted. Always. No one’s ever dared criticize me. Naturally, I’ve had my share of tragedies because of my gender. But I’ve always done what I wanted. I’d add that if Sicilians meet a proud woman, they respect her and let her go about her business undisturbed.

I was young once. I’ve had men, relationships, even strange ones in some people’s eyes. Everyone’s always thought that I was doing the best I could do. But I was strong. I wanted to be strong. But it also cost me a lot of energy. For me, being a woman has been a complete advantage. I’m speaking for myself. Not for the little girl who finishes middle school and her father says to her, “No, you can’t study anymore.” They take the girl out of school. They won’t let her out of doors. She sees a young idiot passing under the balcony and falls in love. She runs away and gets pregnant. After that, they can’t get married and their parents let them live together. After a year, the boy’s fed up and gets together with someone else. Meanwhile, the girl raises her small child and takes up with another guy. That isn’t freedom! The young couple’s lived under an idiotic, sexist, paternalistic society. Their lives will become more difficult and they’ll face more obstacles. They’re uneducated. They weren’t properly instructed in the ways of the world. This is also what it means to be a woman.

It also means today’s teachers who teach you about the mafia at school. They’re finally talking about the mafia. They’re telling children what the mafia is and then they discuss it together. Women were the first to rally en masse against the mafia’s power that continues to humiliate us — that humiliated us — and still makes us feel bad. They’ve been involved in a number of great initiatives. There was something called the Sheet Committee. When the mafia killed someone, the women would hang a white sheet from the balcony as a way of saying, “Im against violence.” If they had the courage, they wrote an article. If they lacked the courage to do that, they simply hung a sheet outside as if it were hanging out to dry to protest against the mafia. These small actions may have meant nothing to the world, but for us, they were really powerful gestures. Today, women are working on themselves. Male chauvinism still lives on. Men shouldn’t be in power for the next 50, 100 years. No more. Let them tend the vegetable garden and entrust politics to women. We’d be better off. Many things could change. Because women are more beautiful. They’re more real, more authentic. What do women they care about power? We have a saying here: leading is better than fucking. This is a male point-of-view that’s laughable. Yet, it still holds true today. And, perhaps, the same could be said about the rest of the world.

Q: What differences do you see between the Sicily of the past and the Sicily of today?

Sicily today is more aware, less a victim of the mafia. Today, society’s corrupt in the sense that it’s complicit with the mafia. It wants to keep that system in place because Sicily knows the mafia earns a lot of money, like Berlusconi who earns a lot of money. Mafiosi love these figures loaded with money and beautiful women. The mafia and Berlusconi have money and beautiful women. In the past, rich folks were the mafia’s slaves. Women were men’s slaves and the men were the mafia’s slaves. Today, there’s a greater awareness that the mafia is something negative. That sells drugs. That exploits. That incites violence. We didn’t destroy the mafia. And this means that Sicilians continue to want it. Because if they didn’t want it, they wouldn’t be complicit. They still are now. But they’re complicit without being the a slave to the mafia. They freed themselves from that kind of slavery. Those who are its accomplices, want it by choice.

There’s a marvelous side of Sicily that struggles, that renounces financial well-being, its tranquility, to combat the mafia. People are killed because they want to do their duty. We have to have respect for Sicilians who fought against political corruption and the mafia with their very lives. They sacrificed their lives to defend us. To free society of mafia bullying. At the end of the 1970s, there were struggles, sacrifices, heroes. I know them all by heart. I was a photographer. I remember all the dates. Even today when I’m walking down the street, I can remember, “There, there, there.” (gestures with hand to indicate where mafia victims met their fate, Ed.). They are the dead and they changed Sicily’s reality so that we’d become aware that there was something to fight against. No one fought before. Judges? Almost all corrupt. The police? Almost all corrupt. And politicians? Complicit with the mafia. Today, something finally changing. The Sicilians have changed.

The mafia’s still very powerful. Maybe more powerful than before because it wears a tie, uses a computer, sends its children to study in Switzerland or New York. But there’s greater awareness today. We know the mafia’s there, that it’s a brutal beast that does dishonor to our wonderful island, which has a rich cultural legacy. But that for more than a century has put up with its presence, sustained and desired by the government, by a long line of governments that we’ve had. We were alone. Our hand were tied. When it’s said that the Sicilian keeps silent, omertà, that means he’s complicit. Otherwise, they kill him and no one comes to his defense. Therefore, he doesn’t speak because no one stands up for him. That’s changing now. Citizens are coming together to fight racketeering, to fight against drugs. Women are uniting to stand up to the mafia and are publicly demonstrating against it. In the past, the word “mafia” was never uttered. When I was a child, we knew there was mafia in the countryside, but not here in the city. It didn’t affect us. The mafia was the stuff of legend that came from somewhere else. Then, it arrived in the city. When we were children, there was great poverty, but there was no violence. We were good people. There was more respect back then. And then came consumerism. That’s what stole our culture. Money, economic power, consumerism took a lot away from us. It will take centuries [to repair the damage.

Q: How do you position Sicily within global culture? How do you think Sicily is reacting to this?

In my opinion, badly. Badly because a good part of the population didn’t go to school. All of the different governments that we’ve wanted an ignorant people. A people that was unprepared, unskilled. Many don’t know how to do anything. They have no real job, no real training. Right now, it’s over for fifty-year-olds. In twenty years’ time, things will be different for the younger generation. What does globalization mean for us? That they makes us destroy oranges? Once, I had to photograph these beautiful oranges. Heartbreaking, if you think about the countless children in Africa suffering from rickets or, here in Sicily, undernourished children. And we go and destroy oranges to maintain the European market. Come on! Globalization is irreversible. There’s nothing we can do to stop it. And its harming poor populations so we don’t stand to benefit much from it.

Q: Do you believe Sicily is losing its values? What can be done maintain them?

They can’t be artificially maintained. Of course, we have to safeguard Sicily’s popular festivals because they pass on traditions. For instance, I’ve photographed many processions. Not for Christ, but for what’s occurring outside of the procession, which maintains an authenticity. People dressed in their best, their faces, their elegant clothing that’s a bit bumpkinish. It’s really lovely to photograph. One time, I arrived in a village to take pictures. The following year, I wanted to photograph this procession again. I discovered that that a director had been paid to stage it. He had ruined the procession. It was shameful. The procession had become something false because the actors were horrendous performers. Before, the procession was organized by the local residents in an artless way. So, we have to be careful. I don’t set much stock by tourism. It will destroy us and we’ll build lots of hotels and make fake burgers. If you visit cities with heavy tourism, you’ll see that the landscapes are ruined, that everything caters to other cultures that aren’t your own. So you copy what’s done in Madrid, London or New York. Market needs? It doesn’t seem like that’s right for us. I think we have to be very cautious and create a tourism that stays in the hands of small local enterprises, the opposite of large hotel holdings, which would be disastrous. It’s already a disaster in Florence where you can’t even walk.

Q: What role should Sicily play in the European Community?

In my opinion, Sicily should engage with other Mediterranean countries to play a more significant role. I think they’re doing many things that are wrong. Maybe they’ll find their way. It’s possible that the European Union will make us strong. But, for what? To make wars? I hope not. The process is irreversible now and it’s in this moment of globalization that strengths need to be created. I really don’t care. I like the other European countries. I love traveling. But I don’t get what we have to accomplish with the Germans, except for visiting each other’s countries. Maybe we’ll get progressively weaker. I’m standing by. I still don’t feel serene. I see that all the benefits coming from Europe go to the clever folks. There so many of them that latch onto these bogus projects. Yet, there are great projects out there that aren’t given a chance. We still have to learn to live in Europe together, respect and work for each other. It’ll be a challenge. I’d like the whole world to be just so: all working together without wars or excessive power. Instead, we’re building something that’s another power in relation to America and other nations. Let’s see what happens.

Q: What future do you foresee for Sicily?

A polluted future. I see a polluted Sicily. If we don’t get a move on and enact severe laws, terrible laws, targeting those who pollute, that have polluted, and ruined our land… This terrifies me. I also see a mixed economy and that the mafia will gain economic power. That’s how we’ll be handled. Maybe that’s a fantasy. Maybe a fear. But that’s the feeling I have.

Q: Any final words you’d like to share?

I want others to know that we’re fighting. We’re fighting for justice so that it take’s the mafia’s place. And I want others to know that we’re alone. That we’re weak and that we need help. We need solidarity. Solidarity that the people who were murdered for our land didn’t have. I ask for solidarity. I ask for trust, even if we have many faults. I feel guilt for not having really fought against the mafia. We should have started fighting a lot earlier. I ask for solidarity. I ask for help. We ask for help. We can’t stay bound to a story of mafia that’s played out over the last hundred years. Once, we had a great history — we have a great history behind us — always in connection with the Mediterranean.

Afterword by Gia Amella

For me, Letizia Battaglia is audacity, honesty and justice. I’d always sought out strong female role models to emulate in my own family, probably because my own mother was passive and never found her own voice, still painful to me. More than anyone I’d ever met, Battaglia exuded the strength of my father’s older sister, Stella. My aunt had raised three children on her own after her Greek-born husband, Tony, suffered a fatal heart attack at 38 years old. His restaurant was destroyed in a fire – hushed voices in the family say it was arson – in the early morning hours. Aunt Stella, who had worked alongside her husband up until the fire, found herself without a job and having to support her family. Somehow, she lifted herself up and forged a successful career in human resources in downtown Chicago. When she was diagnosed with breast cancer in the 1970s, she began offering her support to other survivors long before prevention education became widespread, eventually founding a survivors’ group in Greece, where she traveled to every few years with the kids in tow. The cancer eventually came back. She died in 1990 on Good Friday with our family at her bedside. We all believe she planned to finally let go on that day.

Battaglia, too, had raised three daughters on her own. She found her way into advocacy rights for women and society’s marginalized. She and my aunt shared a heritage. Aunt Stella was the epitome of the Sicilian-American woman, at least to my own vulnerable eyes that had already seen tragedy too early on in life. My aunt was fearless, a force to be reckoned with. She taught me to look inside myself for strength even as death’s specter closed in on her, just as Battaglia had surely tapped deep into her core for strength for every photograph she took of a bullet-ridden body sprawled on the pavement, or of a malnourished child standing outside of a Palermo tenement building. I was lucky to have a family member like my aunt who showed unshakeable courage in the face of terrible, terrible things. Now, I wanted to meet her Sicilian counterpart.

Fabio Sgroi had introduced me to Letizia Battaglia. He was a photographer in his own right who, like Battaglia, had spent decades documenting life across his native city and Sicily’s interior. Early on, he had worked at the now-defunct daily newspaper L’Ora for which Battaglia had taken some of her most iconic images. There, she’d collaborated alongside Franco Zecchin, a Northerner, who matched Battaglia’s fearlessness and her zest for rooting out a good picture during the mafia’s terrible reign of violence. Zecchin had also been her long-time companion. When she graciously assented to an interview at her Palermo apartment in the summer of 1999, I had no intention of steering the conversation toward her affairs of the heart. Settling into our chat, she made passing reference to her own personal tragedies, I didn’t probe further. Nor did I want to. I wanted to learn about the Sicily she knew and that she’d extensively photographed. About the Sicily she adored and, at times, despised. I quickly realized that how I had worded a question could trigger a harsh response. It wasn’t anything personal, I knew. I liked her immensely.

For instance, Battaglia was put off when asked what she considered sacred. It was a pat question that I invariably asked people I interviewed. It was ambiguous enough of a term to allow the responder to interpret the word as he or she saw fit. Cretinaggiani, all bunk, was the brusque reply. She didn’t believe in the sacredness of anything. She paused, scanning her mind for a response, maybe out of politeness. In the past, sacred meant a woman’s honor, she said in a softer tone, what a woman had between her legs. There was more. Sacred meant money. It meant wasteful consumerism that cut across all social strata. What about profane? She didn’t like that word either. Later on, I understood that those two words could have set her on edge because they were, when asked point blank, seen within a religious context. They were too reductive to exist inside her sphere of experience. Battaglia had witnessed all forms of human depravity that plummeted straight to bottom of Dante’s last circle of Hell, like a massive boulder tied to a flimsy string and hurled downward. How could she possible give a stock answer?

Battaglia was ready to move on. “All my life I fought for things not to been seen as sacred or profane,” she mused in the shade of her balcony. “Because they were life. Because they were respect. Because they were justice.” The unsmiling child clutching a loaf of bread to her painfully thin body. A man laying face-down next to a pool of blood, a naif Jesus tattoo blazoned across his shoulder blade and a bullet to his back. An elderly woman in mourning dress arching her back in a paroxysm of grief. A cross-eyed boy sucking his thumb next to another who brandishes a gun. If there was one word to sum up her prodigious body of work, it would be justice, whether images of hungry children or protesting teachers, or random gestures of love or death. That word – justice — resonates even deeper when you think of what her last name means. Battle. Not in the sense of armed combat. Rather, battles waged, personal and professional, on moral grounds against its counterpoint: injustice. The name fit her to a tee. She’d had her share of tragedy and lost loves. Battaglia inexorably moved into the public’s eye, as much for her craft as for her decades-long quest against injustice in all its hateful forms. Reluctantly in the public’s eye at certain times in her life, I got the sense.

As Battaglia settled into a garden chair with a cigarette on that June afternoon somewhere in Palermo’s old city center. She would share what would be anything but a neatly bundled account of Sicily’s darkest days. when a solitary woman walking on Palermo’s streets spelled all kinds of trouble, much less for one with a camera slung across her chest and a sharp eye for a story. Final adjustments for framing, a quick audio-level check and she was ready to talk about her Sicily.

A Chicago native, Gia Marie Amella co-founded Modio Media Productions Inc. in 2006, a video and television production company whose work has aired on leading networks globally. She earned her M.A. in Radio-Television (1993) from San Francisco State University, where she also served as a lecturer in the Broadcast & Electronic Communication Arts Department, and a B.A. in Italian Literature (1988) from the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1998, she received a Fulbright Fellowship and headed to Sicily, where she spent a year conducting research on popular traditions and Sicilian identity. She’s the recipient of multiple awards for achievements in her field. She currently works and lives in Montevarchi, Tuscany.

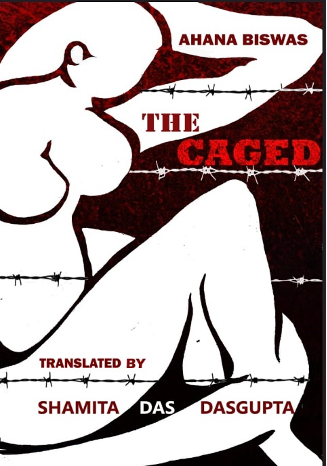

Cover and author photos from Gia Amella’s archive.