I come from a family of 10 children. My father is a teacher. It’s a lineage that has followed us. It’s no surprise that many of the family members at large have gone down that path. It all started with my great grandfather who pioneered Islam in the eastern region of Uganda. He garnered such a huge following in this path with his teachings, this was passed down to my grandfather, who in his own right taught many in the times of our resilient leader, Idi Amin. He however, faced an unfortunate demise at his prime. He disappeared, never to be traced. Rumors are his initiatives lead to this unfortunate happening. Then came my father who is a leading academician in Uganda. He pioneered Makerere University Business School that has been an anchor for many prominent leaders in the society now. He owes it to his mother, a woman who until now is celebrated in our family despite her passing on, and inevitably to his father whose blood he bequeathed.

I come from a family of 10 children. My father is a teacher. It’s a lineage that has followed us. It’s no surprise that many of the family members at large have gone down that path. It all started with my great grandfather who pioneered Islam in the eastern region of Uganda. He garnered such a huge following in this path with his teachings, this was passed down to my grandfather, who in his own right taught many in the times of our resilient leader, Idi Amin. He however, faced an unfortunate demise at his prime. He disappeared, never to be traced. Rumors are his initiatives lead to this unfortunate happening. Then came my father who is a leading academician in Uganda. He pioneered Makerere University Business School that has been an anchor for many prominent leaders in the society now. He owes it to his mother, a woman who until now is celebrated in our family despite her passing on, and inevitably to his father whose blood he bequeathed.

We have grown up in a relatively humble background. Some would disagree, I think it’s subjective. What may seem like rags to one is heaven to another. We lived in flats within the city, opposite the university my father used to lecture at. We shifted housing often many years down the road as I matured. Eventually, I settled in with my mother during my teenage years. Upon leaving high school, I piqued an interest in poetry.

I always used to scribble, it was not until my older sister recognized my work and acknowledged it as “interesting poetry.” Hailing from a background where I felt like a failure during my academic years. This was a huge stroke on my deflated ego. I felt like I was finally good at something just from one compliment, thereon begun my journey into poetry.

The habit morphed into a place I found refuge, a place I rested my troubles. After filling note book after notebook with scribbles and doodles, I went forth and opened a blog; ebrahim-conjolted@blogspot.com. This is when I started my university in India. I was pushed to seek more knowledge on writing. The time was conducive because I was very closed minded and spent a lot of time in seclusion. I hampered the opportunity for me to delve into a new culture and expand my knowledge; however, it helped my writing grow, and helped me venture into music. A thing that I had silently dreamt of but shut out because of the strong Islamic roots I was raised on.

They say when you give a man a path to walk; he is bound to pick up many things, even those that might be frowned upon. I used the Internet to my advantage; I taught myself the basics of poetry and music. It hampered my academic growth but aided my personal growth. I grew to learn more about myself in those years I spent in Bangalore, India than life will probably ever reveal. We are; however, ever evolving beings. So there’s really no guarantee.

Being in India shaped my social and political views. Having secluded myself for those years, I grew distant from the political sphere in my country. I was, despite my state of being aware of the happenings, and the many stories of the disgruntled in the country. Being among those in the Diaspora can frustrate you further more because you feel even more helpless. This all shaped my observational poetry.

When I got back home, it was hard to be welcomed with open arms. People don’t easily open up to you when you’ve been away. You are an outcast until further notice. This made it hard to cope socially, also shaped my perspective in my writing. I believe, on a positive note, my canvas grew broader having been exposed to a different culture and society.

After two years of my return, I was welcomed back by the community and this point marked a level of growth on my journey. My works were published, and purchased after I had a show to enthrall the enthusiasts and supporters. I dropped the ball right after and went back for my masters, another phase of my growth more so musically. I went back to India to pursue my masters. This time I was more open minded having learnt better. I enriched myself more, this led to my works growing leading to my most recent publication, “Ayeh, leave it to God.” A compilation of short stories of my experiences embedded with poetry that is a portrait of those experiences.

In the recent years, African countries seem to be going through a much deeper level of cultural awareness. This is seen in our dressing, and language. Language as our medium of expression now begs most Ugandan artists to choose our indigenous colloquial language over that of our colonial masters. This drives me to the nature of my work, and influence. I have grown up in surroundings that have unfortunately not encouraged my indigenous practices. My schools from childhood have had an array of mixed race students that predominantly spoke English, and when I would go home, my parents occasionally spoke lusoga, a language from the eastern region of Uganda. A language I am glad to be able to speak, and as I mature learn to script some of my works with.

My influences are therefore very westernized and embedded with that of our colonial master. For a very long time, I kept looking at this as a disadvantage the more I grew aware of it. I chose to eventually break free from it and saw it as an advantage if I wielded this power well. I can now write in my indigenous language and in English which has made my work richer in expression and commentary. This has enabled me tap into various topics, political, religious, social, and more so personal because writing has always been a way to self heal from my own worries and troubles.

The political scape hasn’t been one I have heavily ventured in deliberately. I feel like our political state is one that has to be disinfected from the root up. However, it has led me to realize that works that are socially inclined can have an impact on my people and their thinking. So my strive now is to be able to have works that dwell on social commentary and communal growth, to see that we can hopefully have a change in thinking. For the change we need is within, as narrated in my piece, “Mu maaso awo,” which is a double entendre for we see it all before us, and we shall see it in the future. The “it” in subject being our current social, political, and economic times.

The choice of my predominant dialect and the overall fact that I am a poet has rendered my reach very minuscule. This is because a larger mass of our people prefer works written in our local languages and many more prefer works of music over poetry. It’s a challenge as poets, who in a society are key have to overcome. It’s the reason I endeavor to incorporate my poetry with music. My goal on the other hand is to have global reach, which is pushing me to mold my work on that scale, where it’ll appeal and be essential to a larger number of people. I therefore want my works where they’ll be relevant.

Attached is a link to a song that address how higher authority has blinded people and enchanted them to go astray from what should be priority.

Hamid Barole Abdu (born October 10, 1953 in Asmara) is an Eritrean writer.[1] After studying literature in Eritrea, he moved to Modena, Italy, in 1974, where he has worked as an intercultural expert and has published several articles about migration. He is currently living in Uganda where he is active promoting cultural initiatives. His books include Eritrea: una cultura da salvare. Ufficio Stampa del Comune di Reggio Emilia, 1986;Akhria – io sradicato poeta per fame. Reggio Emilia, Libreria del Teatro, 1996,Sogni ed incubi di un clandestino. Udine, AIET, 2001,Seppellite la mia pelle in Africa. Modena, Artestampa, Il volo di Mohammed. Faenza (RA), Artestampa, 2009,Rinnoversi in segni … erranti. Faenza (RA), GraficLine, 2013,Poems across the pearl of Africa. Faenza (RA), GraficLine, 2015.

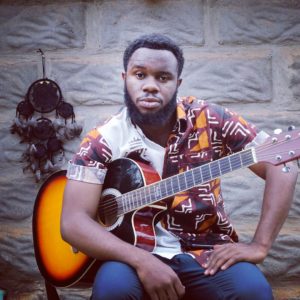

Cover image: photo of Ibrahim Balunywa, courtesy of the author.