From the Introduction by Art Historian and Critic Antonella Uliana

[…]If the artist’s task is to embody her era and to represent collective consciousness, Oksana Šačko’ has fought her own battle and achieved her goal.

Her nonchalance and skill in using ancient and well-established tools of iconography, combined with her ability to create hybrids containing seemingly irreverent elements, turns the meaning of the traditional objects upside down. From works of art whose aim is to make Revelation manifest, they are converted into means of social denunciation.

Her icons bear the indelible imprint of her artistic training, including the great emotions stirred by art early on as well as the burning disappointments she experienced later.

If a traditional icon evokes hymns, praise, and prayer, Oksana’s works embody experiment, reflection and revolution.

They become the meeting place and the clashing point between the rules and regulations of orthodox iconographic art and a violent plummeting into reality.

The direction Oksana Šačko’ takes undergoes drastic changes, no longer indicating the path of beauty and asceticism leading towards the Creator but rather she plunges viewers into the pain of humanity. Once she disassembles its age-old mechanisms through her creative work, traditional iconography becomes an opportunity for a renewed pondering on the phenomenology of the sacred itself and its ability to produce meaning for the contemporary world.

From a manifestation of the Divine icons turn into a window to the world. From a place of abstraction and timelessness, to reality and history.[…]

THE AMAZONS OF THE APOCALYPSE

There is a strange analogy between Oksana Šačko’s life and that of the author of the Apocalypse. Indeed, many scholars believe that John, the author of the last book of the New Testament, found inspiration for his writings during a period of confinement in a prison on the island of Patmos, just like our artist seems to have found her way to painting icons during her French exile.

The word Apocalypse etymologically means revelation, from verb apokalyptein, the act of removing what covers or hides, i.e., discover, reveal. Hence, a powerful word of encouragement and hope.

In a time of difficulty for the evangelist and his community, the Apocalypse represented an invitation to resist against the soft and decadent style of Roman consumerism. And, to reach his goal, John pursued a threefold strategy: demolishing his opponent, constructing an alternate universe and offering a knowledge- based moral imperative.[i]

Like John, Šačko depicts her opponent with grotesque pictures, while presenting to her audience her own humanist manifesto. Just like John who aims to instill hope in the middle of persecution, Šačko, who had to find refuge in Paris because of her activism, asks the viewer to avoid the pitfalls of capitalism or the commodification of bodies: “I am not prepared to accept society as it is and the rules it imposes on us. I’m ready to fight to the end, even though I know it won’t bring about big changes in my generation. But it is a beginning and we are part of a long tradition of people who struggled and protested. I want to sound an alarm bell for the people. I want to wake up all the people who are asleep in their houses, content with their little piece of land and their usual old job. I want to give them a wake-up call, to make them rise and help change the world order. There have been many great ideas that aimed to free people and help them fulfill their ambitions, but capitalism ended up corrupting many of these ideas and so now we see them in a distorted light, not as they truly are. But I think that our ideas, our vision of the world, will not fall apart.”

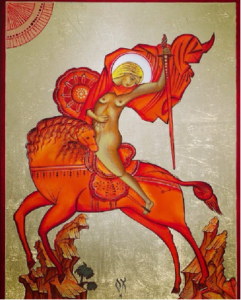

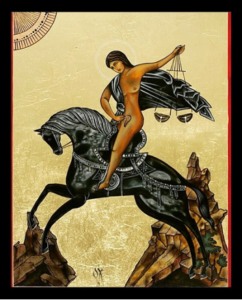

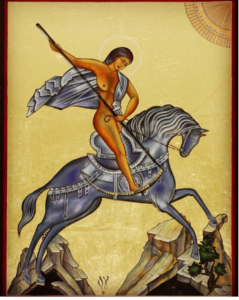

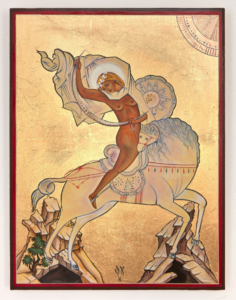

The four canvases painted by Oksana Šačko, are inspired by the image of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse But, upon closer inspection, the four horsemen have become four amazons and, in the installation at the Parisian Gallery, under each of the canvases, the passages of the Apocalypse are dripping black blood, describing the sense of death, along with the subjugation of men and, most of all, of women, which, according to the artist, is intrinsic to all transcendental beliefs revolving around the worship of masters. In the apocalyptic picture, the horses evoke the great forces that dominate history, that is, the dynamics that most profoundly mark human affairs. Unlike the steeds, whose dressing is depicted with an abundance of details that clearly reflect traditional Ukrainian embroidery, the Amazons are shown fully naked, except for a cloak that dances over them.

The red horse draws blood and fire and the Amazon bears a great sword that she uses to do away with the falsehoods of patriarchal society while spurring humanity to seek the truth through a dialogic battle.

The black horse: its color evokes darkness and death. The horsewoman holds the scales in her hand, a sign of measurement. Thus, the scene represents the dearth of ideas and ideals that, the artist believes, characterizes contemporary society (a theme that we will find again in two of his icons of the trinity).

The green horse evokes the livid color of a corpse. The amazon riding it is Death symbolizing the demise of will and moral strength that plunge humanity into the abyss of sloth.

.

.

Finally, the white Amazon rides a mare bearing even more evident references to Ukrainian traditions. The animal’s dressing almost turns into a vyshyvanka, the traditionally embroidered shirt considered one of the most important symbols of Ukrainian identity. The design of the embroidery, the color of the silk threads, the cut of the shirt vary from region to region and are often arranged in such a way as to suggest the idea of protection, like an amulet, a kind of protective armor, also worn by soldiers under the uniform. Embroidering a shirt for someone is the equivalent of embroidering his/her destiny, so the embroiderer, just like the writer of icons must have only beautiful thoughts to convey through needle and thread. And always just like icons, vyshyvankas are kept in the family and passed down from generation to generation. However, this is not where the reference to the Ukrainian tradition ends. In the image, the white Amazon draws a bow while wearing a crown of flowers on her head as a sign of victory. “The crown – Oksana Šačko says – is a Ukrainian symbol and represents the condition of unmarried girls: they are free, young and strong. For us, the flowers represent freedom, independence, peaceful protest. And, in addition, they are beautiful.”[ii]

[i] Claudio Doglio, la testimonianza del discepolo, Torino, 2018

[ii] Femen, In the beginning was the body, Malpaso.

[…] Oksana Šačko was born on January 31, 1987 in Khmel’nyt’kyj in Ukraine, three hundred kilometers from Kyïv . In 1995, still a child, she joined an art school in Nikoš, renowned for teaching Orthodox icon painting and normally reserved for adults.

In 2000, after graduating from the Nikoš school, she enrolled in the Khmelnytskyi Free University. Her philosophy studies caused her to undergo a serious crisis of conscience as she discovered the corruption in religion as well as the power of the patriarchy. This led her to abandoning her religious fervor for feminist activism.

“At thirteen I wanted to take my vows, because I adored the Orthodox icons which I passionately copied, but as I deepened this discipline, I realized that it was a big business and that priests were more merchants than people of God. I continued attending the iconography school to earn a living, but I gave up the idea of becoming a nun [1].”

In 2003 she participated in the political activities of the New Ethics group. In 2008, together with Hanna Hucol and Oleksandra Ševčenko she founded the group FEMEN to raise awareness and encourage Ukrainian women to fight for their rights. In 2008 she moved to Kyiv where she rented a small workshop used to make and paint Femen’s “weapons”, i.e., costumes, masks, body drawings. In 2010, she came up with the idea of demonstrating topless in Kyïv, holding signs that read Ukraine is not a brothel. Three years later, in 2013, as a result of some of the group’s demonstrations, together with some of her associates she was forced to seek asylum in France. In 2014 Oksana Šačko left Femen and her activism took a new form: “I still have my beliefs, but I have chosen to act using other means, to explain my ideas using these paintings which are not on my breasts. It would be so boring to paint the whole of life on my breasts!”. So Oksana Šačko returned to devote himself to painting and, in particular, to icons. […]

Oksana Šačko passed away in Paris, at the age of 31, on July 23, 2018, with a life full of struggles and experiences behind her. This book wants to celebrate his courage, his unwavering determination and her work always aimed at dialogue and against any form of indoctrination. […]

Massimo Ceresa (Rome, 1974) was the head of Mondo in Cammino Veneto and one of the founders of AnnaViva, two associations dealing with the situation in Eastern Europe and Caucasus countries, supporting and promoting solidarity and cooperation projects. He contributed to IAMNESTY, Amnesty International’s human rights quarterly. With Infinito Edizioni he published the novels Dania e la neve (Dania and the snow, 2009) and Sopravvivere nella Russia di Stalin e Putin (Surviving in Stalin’s and Putin’s Russia) (2013). With Carlo Spera Editore he published in 2014 Pussy Riot – Le ragazze che hanno osato sfidare Putin (Pussy Riot – The girls who dared to challenge Putin). His latest book is an investigative work titled FEMEN – Inna e le altre streghe senza Dio (FEMEN – Inna and the other godless witches, Tra le righe libri 2016)

Antonella Uliana is an art historian and art critic, with a degree in Art History of the Venetian Renaissance from the University of Padua; former professor of Art History at the Liceo Artistico Bruno Munari in Vittorio Veneto. She has promoted numerous artists, curating their exhibitions and catalogues, both in Italy and in galleries and museums abroad.