The Poet Attends a Writing Workshop, or Summer in Spoleto

Last night was our sad night; you have to have one,

even though you’re surrounded by Italy, and Italians

talking—for free—in Italian, the language

you paid good money to people to speak to you

back in the States. We were in the same restaurant

we’d been to twice before, the restaurant of

the amazing arugula pizza, and it’s late, and Jeanne and I

don’t feel like talking, and there’s a table of

four angry Russians who are saying in very good English

that they didn’t order any copertos and they’re not about

to pay for them, and the waitress brings over

the owner, who sits down at their table and carefully explains

that a coperto is a cover charge that you pay for being served

in a restaurant. “In Italy,” he says, “you pay for the tables,

the chairs, the glasses, the plates, the silverware,

the napkins,” but the Russians are having none of it;

they’re staying angry, even when the owner

explains that the coperto is the very same thing

as servizio incluso, and though they finally do pay the bill,

including the copertos, they make a voluble exit,

the shortest one of them saying loudly

that they will never enter the Trattoria del Arco di Druso

again, and after they leave, the incident

having taken all of five minutes, the owner,

the two waitresses, and the Italian couple in the room

perform a Mozartian quintet, all of them

talking in turn and in unison, for a good fifteen minutes,

while Jeanne and I sit quietly eating bruschetta and salad,

like opera extras in the background.

Then, just after the owner and waitresses leave the room,

and before the Italian couple finish their digestivos, the man

of the couple turns to us and politely asks us what we thought

of the whole thing, and he is pleased when we agree

that it was pittoresco, because it means that we are on

their side, and we are pleased that we have been included

in the entire event, because we are not rude Russians

but simpatica American ladies who fully believe

in the theory and practice of the coperto,

mainly because then we don’t have to figure out

how much to tip.

We are moderately cheered up now,

but still tired, because we have spent the morning with

our writing class in a graveyard of small temples of the dead,

a whole town of families with names like Bevilacqua and Feliziani

and Cherubini, next to the olive groves outside the city walls,

and then we hurried to a master class for the singers in

the vocal arts symposium, where I wept through all the arias

in a deconsecrated church and then the writers

got to sing, even though we are ink-stained wretches

whose voices are scrunched down in crabbed words

on the page, and then it was on to lunch, with fish

and vegetables and three servings of torta di mele

(for me) and espresso lungo. That afternoon,

we were supposed to write about the cimitero, but

all I could think about was Decoration Day, and how

my mother would cut buckets of flowers from her garden—

day lilies and dahlias and gladiolus—to take to

the Bloodland Cemetery, where her father and mother

and brother John were buried in plots marked by small,

polished granite headstones, not in their own

private necropolis, but under little humps of earth,

open to the Missouri sun and sleet and thunderstorms

and ice storms, close to a stand of mulberry trees,

no church at all nearby, much less one built in the fourth

and fifth centuries, supported and ornamented with

broken and mismatched Roman columns and pediments

and architraves, because the one-room wooden Baptist church

(without a single painting or fresco or statue, because

the Bible clearly says you can’t have any graven images)—

that church was moved away long ago, when the U.S. Army

took over that patch of the Ozarks to build an army base.

And I remembered how important it was to my mother

to decorate those graves with those flowers;

you could see that being a daughter and wife and mother

meant everything to her. And there I was,

dancing around and picking mulberries and trying

not to step on the graves, while my mother’s arranging

the flowers that she’s grown with such dedication

and that she knows will begin to wilt the minute she leaves

this country cemetery with its low sandstone wall. And then

I remembered going, many years later, with my mother

to choose the gravestone for her and Daddy, my mother shaking

with the fact of her mortality, turning to me helplessly

and asking me to choose, and me settling at last

on red Missouri granite.

It’s hot, hot, hot in this restaurant, and though

we were warned it would be hot here,

we’ve been lulled by a week of temperate days,

and we’ve left the fans they told us to bring

back in our rooms and we’re sweating and sticky,

and all of my clothes, not just the ones I’m wearing,

are wrinkled and baggy and sweaty, since I keep wearing

the same ones over and over, because half of the things

I brought make me look fat. But then I am fat, or anyway,

fatter than I should be, except that the things that I brought

that make me look less fat are so stretched out

that now they make me feel like I’m losing weight.

Then Jeanne and I decide that the answer,

not just to lingering sadness, but

to everything else, is gelato, so we walk back

to the Piazza del Mercato and our favorite gelateria,

and Jeanne orders nocciola and albacocca,

and I order bacio and fior di latte, and we walk back

down the winding, uneven streets that are just as noisy

and dangerous as the ones in San Francisco,

what with the cars whizzing by six inches away,

except that here you can pretend to be a small medieval

knight, traversing the black streets and hoping that

the city walls will hold, and we go back to the convent

where we’re staying with the singers in the music workshop,

and where it’s dark and groups of singers are sitting in

the courtyard, talking too loud and trying not

to sing. It’s so hot I have to keep the window

of my nun’s cell open, which means that I can’t

go to sleep, because the singers are young and noisy,

so I toss around for a while, and now my back

is starting to hurt and I decide to get up and do some yoga,

and I do one half-hearted Downward-Facing Dog

and then go back to bed, and I keep on tossing, and

the singers keep on making noise, and time

keeps on passing, until at last I say to myself,

“It’s okay! It’s warm! It’s summer! It’s Italy! We’re all

still alive!” and I pull my rough sheet

over me and go to sleep.

Carolyn Miller is a poet and freelance writer living in San Francisco. Her most recent book of poetry is Route 66 and Its Sorrows (Terrapin Books, 2017). Two earlier books, Light, Moving (2009) and After Cocteau (2002), were published by Sixteen Rivers Press. Her work has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, The Southern Review, The Missouri Review, The Georgia Review, and Prairie Schooner, among many other journals, and her awards include the James Boatwright III Prize for Poetry from Shenandoah and the Rainmaker Award from Zone 3.

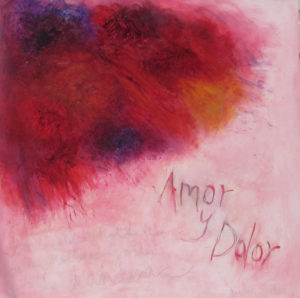

Amor y Dolor

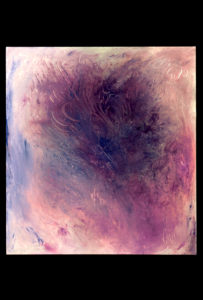

Angel Island, Blue Fog

Carmel Cove N. 1;

Fog Bank- San Francisco

For Sara

Brushfire: Missouri 1948

Lunar New Year

Missouri Woods- Spring N.. 3

Storm Cloud