Working the black Mediterranean, from Timothy Raeymaekers blog “Liminal Geographies” Posted on 21/01/2015 by admin

This somewhat longer post involves a reflection on a number of meetings I’ve had over the last months with African refugees in the city of Bologna, while preparing research on migrant labour and urban marginality. Though these meetings took shape in the context of a travelling theatre project (called City ghettos of today), I am thinking of enlarging my questions into a broader comparative agenda on what some people have started to call, first hesitantly, but ever more publicly and consistently, the Black Mediterranean.

I would like to contribute to this discussion by adding a few, loosely related, ideas around material labour conditions (for more on this dimension see here) as well as emerging hybrid identities in the arena of migrant mobilisations on the Afro-European border (primarily in Italy but also in other places). All of this may result in a research paper later this year.

Recently the Black Mediterranean has started to surface as a term to indicate the cultural crossroads between Africa and Europe. Under the radar of often violent and discriminatory migration control regimes, which make the journey between both continents an uneven experience indeed, a hybrid, cross-cultural exchange is visibly taking place. At first timidly, and always characterized by a geography of racial subordination, the Black Mediterranean represents an emerging borderland, a zone of cross-border encounter between people, knowledge and ideas.

The term draws its inspiration from Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic and was coined for the first time by Alessandra di Maio. While talking at a conference called Black Italia at NYU’s Villa La Pietra lectures last year, she says:

“The term focuses on the proximity that exists, and has always existed, between Italy and Africa, separated (…) but also united by the Mediterranean (…) and documented in legends, myths, histories, even in culinary traditions, in visual arts, and religion.”

Pointing to recent critical texts, like for example Andrea Segre’s African trilogy (South of Lampedusa, 2006; Like A Man on Earth, 2008; Green Blood, 2011) and 18 Ius Soli, by Ghanaian-Italian film maker Fred Kuwornu, she points to the growing exchange between Africa and Italy as a result of booming migration, which is marking the contemporary cultural identity not just of Italy but also of other Mediterranean countries.

In a recent contribution for Social Identities, Esther Sánchez-Pardo writes, for example:

Spain, the historically homogeneous out-migration country is transforming into a site of multicultural interaction as it becomes a destination for members of several Diasporas, many with their own legacies of colonialism and racism.”

Africans in Europe clearly start to develop and active Afro-European (or Afropean) consciousness that uncomfortably sits in the middle between unelaborated colonial memories and new post-colonial struggles.

Di Maio and Sanchez-Pardo indicate a booming postcolonial literature on the northern shores of the Mediterranean, which has been described more in detail for the Italian case by Anna Frabetti.

Interestingly, Frabetti notes, notes, there has been a net difference in Italy between the early 1990s literature –with titles like Io, venditore di elefanti by Pap Khouma, Immigrato by Saleh Methnani, and La promessa di Hamadi by Saidou Moussa Ba– which typically narrated Africans’ postcolonial experience to and through Italians, and the more conscious (auto-)biographies of the 21st century. Books like Regina di fiori e di perle by Gabriella Ghermandi, published in 2007 (which offers the writer’s reinterpretation of Ethiopia’s colonial struggle) and Timira (the biography of the daughter of an Italian fascist general and a Somali mother, written by her son Antar Mohammed Marincola) and Il commandante del fiume (written by Ubah Cristina Ali Farah) more actively try to cast the authors’ personal experiences in the midst of Italy’s problematic coexistence with its former colonies, while directly confronting Italian readers from their own, no doubt marginal, standpoint.

There is a very emotional passage in Ali Farah’s book, which in my opinion indicates this shift very well. It tells the story of Yabar, the son of a Somali military leader (warlord) and his emigrated mother in Rome. Before moving to London, Yabar meets Libaan (a metaphor for Shakespeare’s Caliban?), a young, second generation Somali in the Italian capital, who has somehow lost tracks of his mother (his father abandoned him a college):

“[Libaan] forgot everything he knew, even how he pronounced his name.”

Yabar then helps Libaan to call his mother. He picks up the horn, calls her number in Mogadishu, and pretends to be Libaan:

“… and I see the words form a line in my head, I feel and I hear all of them, they kick and they take their form just like nuts, and I push withmy forehead and my eyes to let them out. The words are hard, they pierce my head… so I again start to push energetically, I feel the words appear in my throat, I can touch their form with my tongue… and I repeat his words ‘hooyo, waa aniga’ and the words ‘mother’, ‘am’ and ‘I’ sound the same in this new language… and I am the mother and the son at the same time. [my translation]

Another surprising evolution has been the development of an African film industry on the Italian peninsula. Since Nigerian Nollywood directors directly started to gain ground across the Mediterranean, they have pioneered a few notable productions, Alessandro Jedlowski writes in this edited collection on postcolonial Italy.

Some of these, like Italian Runs, reduce themselves to simply mentioning the experiences of Nigerian migrants in Italy while being filmed in Nigeria.

With this geographical shift, the drama of these Italian Nollywood movies also slightly changes. Akpegi Boys is more a Nollywood-style gangster movie, with violent characters combating their criminal turf wars while making use of the classic references of the Nollywood genre like soapy love drama and ‘black’ magic. Blinded Devil in contrast has been citied as a form of “guerilla cinema” for its active social realist engagement. The mixed cast includes prominent Italian actors like Pif (maker of la mafia uccide solo d’estate and former journalist of the satirical programme Le Iene) and Vincent Omoigui, the co-founder of GVK productions.

More than a simple crime movie, Blinded Devil analyses the actual construction of illegality as a result of Italian immigration policies while dealing with the often defiant ways in which Nigerian criminals try to bend these discriminatory regulations. In this regard, Jedlowski writes, it is funny to note how Italy’s emerging Nollywood industry really gives a rather original twist to dominant perspectives on marginality and exotism, as Italy is rather placed on the margin of the Nollywood film industry.

Finally, Africa’s presence in Mediterranean Europe increasingly involves a musical journey as well. Reflecting on the recent death of Naples-born musician Pino Daniele, who described himself as nero’ a meta’ (half-black) for his major influence from Afro-American music (a me mi piace o’ blues is one famous song on this album), I went on a search for more examples. One could mention Enzo Avitabile, for example, who played with many African musicians like Africa Bambaata and Mori Kante. One of Pino’s permanent musical companions was James (giamicello) Senese, a son born from a young Italian girl and a black American soldier who came to liberate Naples in 1944. Like Pino, Senese grew up in Naples Sanita’ neighbourhood, balancing his chances in a practically stateless, multicultural micro-society strangled by abject poverty and urban marginality, as James explains in this wonderful interview (in Italian).

Because of this black American influence since World War II, Naples has traditionally been the centre of the Afropean musical and movie scene (with famous movies like Paisa’, featuring Robert Van Loon as Joe, the black American soldier). Fred Kuwornu is currently trying to re-propose a documentary on black presence in the Italian filmographic tradition called Blaxploitalian, which features many other, less known examples. Still in Naples, one cannot forget the enormous inspiration of Raiz, whose band, Almamegretta, not only introduced dub cross-over in the Italian musical scene (they were among few bands who played with Tricky’s Massive Attack) but has had a major influence on Italian rap bands.

Another strand constitutes the merger of traditional, South Italian music with (mainly West) African rhytms and instruments. Rocco De Rosa, for example, has produced several discs combining these different musical traditions (including a long-standing collaboration with Martin Kongo). He organizes a yearly festival in the Sardinian locality Castiadas where he invites West African musicians to share and unite their skills (last year for example it included the Senegalese-Sardinian band Chadal).

Thanks to these cross-over experiments South Italy’s cultural scene has rapidly transformed into a vibrant encounter between cultural traditions situated north and south of the Mediterranean.

The Racial Geography The racial Geography of the Black Mediterranean

Posted on 21/01/2015 by admin

The Black Mediterranean has recently started to surface as a terminology to describe the cultural crossroads between Africa and Europe. It indicates the emergence of a vibrant cultural borderland characterized by growing proximity between African and European cultures in the area of film, music and literary expression. This post is an attempt to situate this borderland in the geography of racial subordination black Africans in Europe, specifically in Italy, continue to be subjected to (for more on the cultural dimension of the story see here).

The last years we’ve seen a rising interest in migrant struggles by European activist networks. Media and academic attention has turned towards exploitative labour conditions (for example of African labour migrants in South Italy and Spain) as well as emerging self-organized movements and revolts (for regular contributions see commonware, connessioni precarie and Melting Pot Europa).

This rising interest comes not entirely as a surprise. Salvatore Palidda (in his book Racial criminalization of migrants in the 21st century) writes that Italy has been at the vanguard of racial discrimination in Europe for the last twenty years:

“Undoubtedly the country that has advanced furthest in neoconservative development, Italy has been pursuing and reproducing, for twenty years now, the transformation of immigrants into clandestini, both as a formidable resource for the country’s economy, and as a politically profitable scapegoat for the racist nature of the right’s Crime Deal, with its corollary of mayor-sheriffs of the left and the right and homini novi of the so-called Second and Third Republics (…). Italy has become the first European country at war against refugees and migrants.”

Ever since the publication of States of Grace, Donald Carter‘s ethnography of Senegalese migrants in the Northern city of Turin, in 1997, the main concern has been with Italy’s problematic, even schizophrenic relationship with migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa.

A commonly used terminology is that of razzismo democratico, a set of widespread implicitly racist attitudes that has become inherent to Italy’s political landscape. Razzismo democratico has provided the basis of innovative studies over the past few years, in Italian (for example Rivera’s Metamorfosi del razzismo and Faso’s Lessico del razzismo democratico), and in English (for example Pratt and Grillo’s The politics of recognizing difference). A few recent ethnographies are also worth mentioning, for example Hans Lucht’s Darkness before daybreak (about Ghanaian migrants in Naples) and Riccio’s and Grillo’s Translocal development (about circular migration between Italy and Senegal).

These writings make clear that certainly not all Africans have willingly accepted their subaltern status. For example, Pina Piccolo writes in this post (in Italian), black Africans have frequently been at the forefront of organising collective protest against exploitative labour regimes in the country. Whether it concerns the denunciation of public waste management in the city of Imola (as this video shows), the spectacular protest against the Carlo Erba factory (where several Africans migrants tied themselves to a crane, as Vittorio Longhi describes in his book The Immigrant War) and, most notably, the collective manifestations in Rosarno and Nardo’, where thousands of African day labourers took to the streets in defiance of their systematic exploitation by organized crime and a rashly subservient Italian population (as shown in numerous web documents, most notably by Libera and stopndrangheta), there has been a rising consciousness among black Africans that their presence is indispensable for maintaining Italy’s, and by consequence, Europe’s welfare economy (see for example the book Ama il tuo sogno, about the organization of collective protest in Puglia by the Cameroonian Ivan Sagnet, who is now a prominent trade unionist now).

Whether this means that, according to Antonello Mangano, “Gli africani salveranno Rosarno, e forse l’Italia” (Italians will save Rosarno, and maybe Italy as well) remains an open question. Fact is that black Africans occupy a preponderant role in the organization of collective protest in sectors that are typically situated on the periphery of the traditional labour struggles in the country, notably in logistics and agriculture (for more insights see the January 2015 issues of the South Atlantic Quarterly, with excellent contributions from Maurilio Pirone and Domenico Perrotta).

Take for example, Ahmed. I met Ahmed last summer in a squat in Bologna, which had been occupied for some time by a local syndicate called ASIA-USB. The building, a former dental practice, was between 100 and 120 people, almost all are from the Horn of Africa. ASIA-USB is one of a few syndicate organizations that have jumped to the defence of Italy’s migrants who are forced to fend for themselves in an institutional landscape characterized by systematic neglect.

After arriving from Somalia at Lampedusa in 2009, and receiving a temporary refugee permit from the Italian government, Ahmed had tried several times to escape Italy, to Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and Norway. But each times he was sent back after recognition of his fingerprints (European countries share data of incoming migrants in a central database called EURODAC). Ahmed, in other words, has been a dublinato, a victim of Europe’s official policy of repulsion. After bluntly being told by Italian border police to fend for himself (after his return from Finland, they told him: la citta e’ grande, in otherwords: get lost, how you survive is not our business), Ahmed has travelled through various official and unofficial structures throughout the country. He stayed for a while in the former military barracks of Francesco La Marmora in Turin, which had been refurbished for the purpose of hosting migrants from the Libya emergency for a year. He lived in several squats, including Via Slapater in Florence –also known as ‘little Mogadishu’ for its majority of occupants from the Horn of Africa. And, like many of his fellow African refugees, he took on several informal jobs, including as a day labourer in the fields close to Turin, and a as temporary worker in one of Europe’s logistics companies close to Bologna.

Black Spaces

To some extent Ahmed’s journey is reminiscent of Heather Merrill’s work on black spaces (see for example this article in ACME in a collection I edited): the shelters, detention centres, condemned urban buildings, and other locations representing those who, by virtue of their asylum status and association with African territories, are rendered non-citizens, even though they are an integral part of modern Western societies and the economies that sustain them.

Black African migrants like Ahmed, who have been expulsed from the official refugee regime, frequently take up jobs in the agricultural and logistics sectors, which typically utilize informal forms of labour contracting (called caporalato) to meet their just-in-time delivery objectives. Economic crisis and liberal economic demands have systematically served as an excuse to disintegrate historical labour rights embedded in a system of cooperatives and trade unions, both to the North and South of the River Po. Instead, locally established multinational companies in North and South Italy (like for example IKEA) as well as international logistics companies like TNT and SDA now prefer to outsource labour to a chain of, often obscure and difficult to trace, economic front shops. Like a system of Russian dolls, these smaller companies meet the eternally fluctuating labour demands of major international logistics concerns.

Spatial Memories

At the same time, this returning experience of cross-border Afro-European journeys, through improvised asylum centres, temporary settlements as well as ‘illegal’ precarious jobs, also suggests the importance of specifying the geography of exploitation they are subjected to. Concretely, it demands a broader reflection on the spatial construction of illegality: the question how distinctions between legal citizens and illegal ‘outlaws’ is consciously being inscribed into legacies of racial subordination and imperialism that characterize these geographic fabrications (see for example this splendid video document by Alison Mountz).

One important stopover point in Ahmed’s journey, for example, constituted the Alessandro la Marmora army barracks in Turin. The barracks are located in a central part of town, on a hill overlooking the Po River. It’s as an irony of history that these barracks have been instituted during the first Italian colonial presence in the African Horn, while Italian officials were concluding their first agreements with the Somali sultanates in the late 19th century. During the Second World War the barracks served as a prison where political opponents to the Fascist regime –which was fighting its own war in the Horn of Africa– were interrogated and assassinated.

In a splendid video document, Gianluca and Massimiliano De Serio re-evoke this historical memory with the collaboration of the Italo-Somali writer and actress Suad Omar. They consciously use the voices of Somali migrants who at that time had just been dismissed from this decaying military structure. In their own way (and making use of a particular Somali poetic tradition, of the chain poem) the subjects of de Serio’s movie take charge of their, and Italy’s, history while at the same time they actively rework the experiences of being uprooted from their countries of origin through the instrument of oral culture and poetry (see here for a somewhat longer fragment featuring the image above see here).

To some extent, the experience of these African migrants places postcolonial marginality at the centre of the Italian urban fabric. Rather than a neat borderline between included and excluded populations through some form of territorial stigma, as Loic Wacquant would call it, the different sites Ahmed and his fellow African migrants travel through constitute a diffuse geography, a fluid network of mobile occupied places, which adds interesting new layers of spatial distinction to this post-colonial presence on the Mediterranean peninsula.

Together with the temporary host centres, the many occupied buildings, squats and temporary settlements function as an alternative system of refuge, which partly resists and is partly absorbed by the officialised migration industry that channels migrant bodies through the asylum system in Italy and on the continent as a whole. Via Slapater, Beretta (Bologna), La Peschiera (Torino) and other buildings in Milan, Rome, Florence, form part of a network of occupied places, a new migrant topology, which remains connected through a myriad of cultural organizations, syndicates and other associations (most notably the ce

ntri sociali concentrated in the larger metropoles) that criss-cross the country as well as the old continent as a whole. In Rome, for example, migrants have occupied entire buildings. The most notable of them, Salaam Palace, has a reception and cleaning service; 4Stelle, in Tor Sapienza, has a school and restaurant (illustrated in this fabulous web document). In Turin, ExMoi has its own website, a school and a conference room where it regularly hosts political discussions. In Bologna, a map and a website (ZIC: zero in condotta) inform migrants of new and imminent occupations.

These new migrant settlements typically defy not only the traditional territorial dynamics of spatial segregation between included, fully recognized citizens and ‘denizens’ –residents with not quite the same labour and citizenship right. They also challenge rural and urban divisions. Italy’s countryside is dotted today with improvised labour camps, or ‘ghettos’ (term that clearly reflects the ambiguous representation of African presence in Southern Europe), which accommodate sometimes up to 500 permanent residents and their daily needs for food, clothing, and drinks. Typically, these ‘ghettos’ form part of a circular migration pattern with Sub-Saharan countries of origin, for example between Puglia and Burkina Faso (see for this interesting ethnography by Benoit Hazard) and Emilia-Romagna (as described in Bruno Riccio‘s work on the Murid Brotherhood here and here).

Focusing on these cross-border networks certain authors have warned against a reified conceptualization of migrant subjectivity either across bipolar or transnational lines. While the transmigrant space typically remains a gendered space, it makes sense to also invoke migrants’ liminal condition between African and European life worlds, which are giving rise to new, hybrid identities that are the outcome of these persistent economic contradictions between both continents. This condition necessarily puts into play the hegemonic forms of constructing membership and dependence within the community of origin as well as in the hosting country.

Out of the Ghetto

In Puglia, the ghetto of Rignano has a fluctuating population of 1500 people, mostly from West African origin, who over the 30 years the ghetto has existed ha

ve opened shops, car mechanics, bars, restaurants and brothels. Similar Afro-European settlements exist in Nardo’, Cerignola (Ghana House), Foggia, and Vittoria (in Sicily). In Boreano (Basilicata), a local organization called fuori dal ghetto has organized a school, a music festival and a cooperative for the production of tomato sauce [movie fragment]. And they are not the only ones. The cooperative SOS Rosarno, which tries to reunite African migrants victimized by organized crime, is currently selling its oranges across the country. In Lazio, Puglia, Calabria and Basilicata, other organizations are taking the lead (one of them, Osservatorio Migranti Basilicata, recently organised an encounter to stiffen the organisation of African cooperatives in the South of the peninsula).

It is clear that these emerging forms of collective self-organization are rapidly reformulating the relationship between official, state policies and the expanding non-profit sector involved in the management of refugee accommodation, assistance and services in ways that so far have been only little understood.

A version of this post appeared in La Macchina Sognante N. 1

Timothy Raeymaekers is a scholar and professor of Geography at the University of Zurich. The author of numerous books and articles focusing particularly on Africa, he is involved in many projects related to borders, colonialism, new forms of resistance, the Black Mediterranean. He organizes international conferences and round tables often on issues surrounding The Black Mediterranean, migration and racism, has designed and maintains the blog Liminal Geographies.

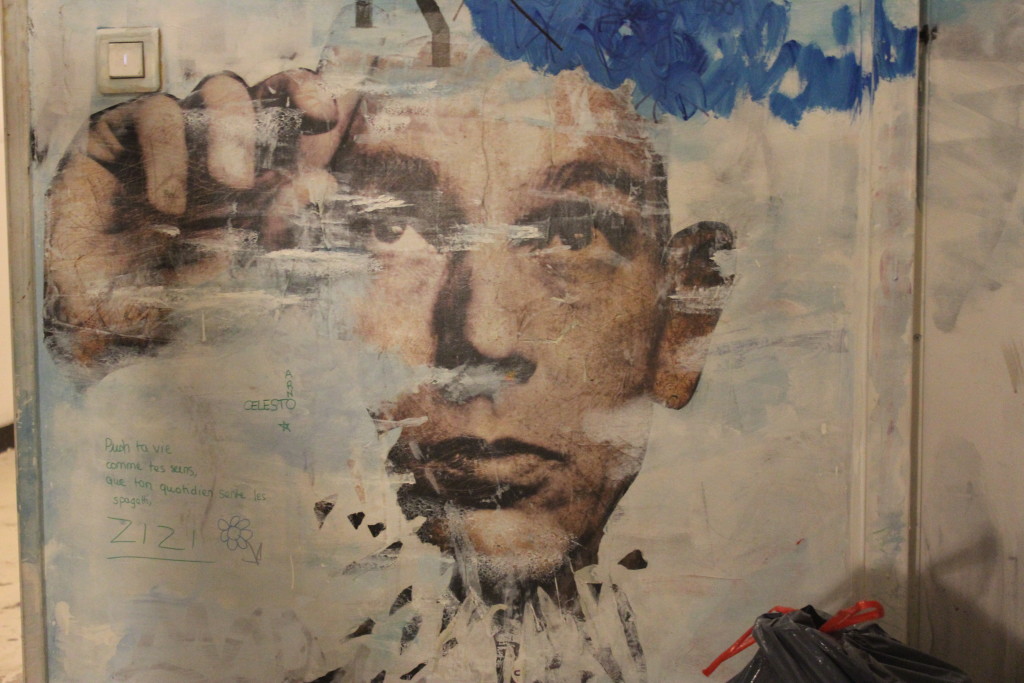

Featured image: Photo by Melina Piccolo.

Comments 1