by Pina Piccolo

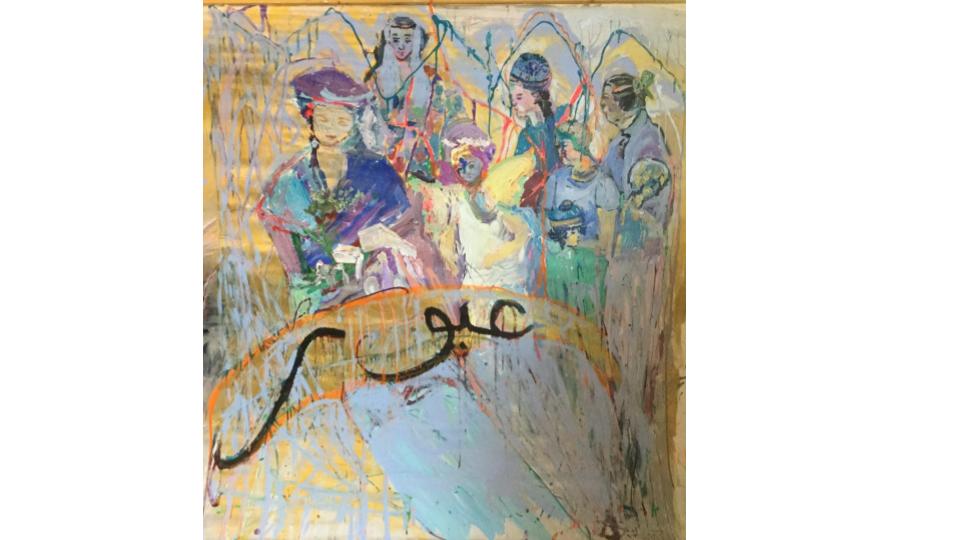

Two poems from the collection Elle are available in English translation in the Out of Bounds section of this issue. The cover art is by Laure Keyrouz, Crossings.

***

As announced by its title, Laura Fusco’s French language collection Elle (Editions Unicité, 2024) is teeming with female presences: children, girls and women of all ages from a vast array of parts of the world from Afghanistan to the Philippines, India, Indonesia, South America, in the most diverse social settings, depicted in a great many psychological states and relating to each other in myriad ways.

Composed of 25 poems, including a few longer ones, Elle retains an airy, vivacious register in spite of the coercive circumstances endured by many of the female characters dominating the space of the various poems. Because of its subject matter, the collection could have potentially turned into a gallery of heaviness and despair, and indeed just a few of the poems are somewhat didactic and read like a newscast disseminating information about the sorry state of the world (many of the tableaux are set in India, in the direst social settings of caste and gender violence). But, in their antiseptic quality, they serve as a stark reminder of statistical realities and counterbalance the vast majority of poems, which, instead, is written as a lyrical reportage from inside the communities. The poems are recorded in media res, which lends them a certain dynamism and piques the attention of the reader, without an attempt on the part of the poet to provide orderly and definite boundaries to experience. From infancy to old age, the women depicted in the collection are recognizable in their everyday life in various settings and psychological states: by the sea, in crowded neighborhoods, at the market, at school, next to karaoke bars, flying kites, polishing their nails, diving from great heights into the sea, engaged in studying or housework, minding their shop, handling cans of spray-paint, taking care of others and themselves, and variously making their way into the world. The metaphors often take unusual directions as the poet seems to be setting up the reader for surprising, paradoxical breakthroughs.

As with all beings endowed with agency, they experience many advances as well as setbacks, harbor longings and resignations. Laura Fusco masterfully renders this dynamic psychological space, mimetically reproducing the thoughts and language of women she has actually come into contact with. Thus, exoticism and pietism are warded off, as her voice is not that of an omniscient poet gazing from above and bestowing an abstract lyricism on the scene. At times, one can intuit the perplexed gaze of a writer from a different generation, especially in the quick portraits of young people engaged in social media exchanges, and handling technology for their own, at times capitalistic, ends. At others, one can detect a touch of envy for the energy of rebellious youth and their excitement as they face environmental and climate challenges, forming communities, struggling, losing yet persevering, as time is still stretched in front of them. This energy feeds the writer, though of a different generation, and spurs her in her creativity, maintaining it fresh.The heart of the activist beating in the poet, in fact, emerges as she recounts the blinding of a Chilean girl: / Today Lady liberty /was shot in the eyes/ by the police / in a cotton-like morning / […] her blindfold a symbol, like that of other young people who had been blinded by the police /in a day full of flowers / with the sky chomping at the bit / a sky you lovingly hold in your hand /.

In the opening poem, the female protagonists are speaking from a neighborhood of Navotas, a fisherman subdivision north of Manila that has experienced a great demographic rise in recent years. This fact, however, is established only well past the midpoint of the poem, so the reader may be thinking they are inside a high density favela, only to find out that it is a relatively more benign place than others the inhabitants have left behind: as it has often become the home to an army of newcomers from the countryside or more densely populated urban settings. This vibrant community contains the voices of seamstresses, estheticians, young women who moved in with their great-grandparents who had settled there from generations:

“I am afraid at night” / Those nights with not a breath of wind / And not a voice heard, / And the moon is a nail in your head for all the light it shines” (translation mine)

Contrary to the readers’ expectations, it turns out the fear is not tied to the dread of impending gender violence, but,being near a cemetery, is actual fear of the dead. Fusco links together power images of life and death coexisting side by side, unrolling a linked series of metaphors and metonymies, deeply rooted in the actual lived experience of the people there.

In its richness and overt standing with life and freedom, this is a refreshing collection in which poetry takes risks and successfully achieves a balance between the lyrical and the journalistic.