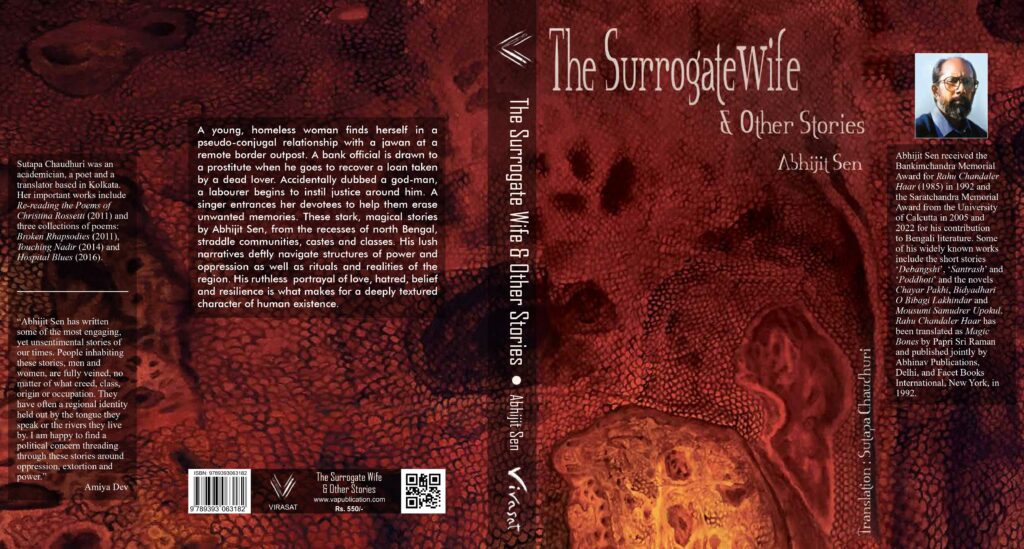

From the short story collection The Surrogate Wife and Other Stories, trans. Sutapa Chaudhuri, VIRASAT ART PUBLICATION, December 2022. Cover artwork by Ginevra Cave.

I had boarded the train from Jangipur quite early in the morning. It was the Janshatabdi Express. This was a new train on this route. The train looked beautiful in shades of white and sky-blue. It ran very fast too.

I have to go to Salar in Murshidabad. But this train would not stop at Salar station. It stopped first at Jangipur, then at Azimgunge, after Azimgunge came Khagraghat in Baharampur, then at one go it reached Katoa, my reckoning of the train’s route was somewhat similar to this.

My calculations, though not out and out adventurous, was of course slightly risky. The risk was simply that I was pre-supposing that the down Janshatabdi, by which I would be travelling, would stop for sure about one or one-and-a-half kilometres before entering Salar station. Because, I knew, it would be the time for the up Katoa–Azimgunge passenger train to get the signal to enter Salar station. And in the meantime, benefitted by this situation, I could then walk those one or one-and-half kilometers down the rail-track, and climb up onto the platform of Salar station and finally reach my office on time.

Although my office was at Salar, I used to live in Katoa. As the train crossed Tenya station, I got up and stood near the door on the left. Malihati was four kilometres from Tenya, and Salar was at a distance of three kilometres from Malihati. Sounding its horn very loudly, the train crossed Tenya. I stood at the door leaning slightly outside. A few minutes later the train crossed Malihati, and advanced towards Salar. I watched the signal post, and in a moment the arrow pointed downwards just as I had expected.

I went inside, pulled my bag from the luggage rack and came and stood near the door. The train sounded its horn, slowed down and finally stopped. I came down by the door on the right. On this side, the slope from the rail tracks was quite steep . I left the tracks and started walking forward on the flat land adjacent to it. It was difficult to walk on this side as it was rough and full of potholes. Moreover, every eight or ten feet away, a short babla tree stood with its huge canopy and thorny branches to ward off any wayward wayfarer. I was forced to stop. Within two minutes or so, the train began to move towards the station, leaving me alone. I searched as far as my eyes went, but could not see anyone around. On the left of the tracks was the silhouette of an extremely distant village across the fields of Talibpur. On the right, was the hazy border of the faraway roads that lead to Kandi. Kandi was a town on the margins of the plantations marking the border between Salar and Malihati. Those roads were lined by huge sirish, neem, and babla trees. Yesterday a big storm had raged over parts of Murshidabad and Birbhum. Along with the storm, the area had seen a spate of heavy rains too. As a result of the storm and accompanying rain, the harsh weather of the Rarh area, in mid-Baisakh, seemed comparatively softened, and within the limits of endurance today. The clear sky and the trees and groves, awash with the pre-monsoon rains, now looked green and stunning in this gentle breeze. I felt a sudden surge of strange energy in myself . Just a few days ago, the fields on both the sides were full of high-yielding paddy. Now they stood empty. After harvesting, the peasants had taken the crop home.

Just as I got up on the rail tracks once more, I observed that someone else was there. It was a woman. I watched her from a distance, that is, of at least fifty to sixty feet; then turned my back and began to walk. But the next moment, I turned around and looked towards her once again, the woman seemed quite familiar to me.

Why, of course I knew her! I thought, extremely pleased. There, I surely knew that gait. On her back hung a simple cloth satchel usually carried around by the women of the Vaishnav community; the woman who was approaching fast in my direction, with her arms spread out, was Sonamoni Dasi for sure.

She must have recognized me a while ago. For she called out from a distance, ‘Gosain!’

I stopped and raised my hand to express my surprise and pleasure at seeing her there. Sonamoni Dasi was approaching quickly. She took long steps. Her eyes and face beamed with joy at this sudden, and unexpected, reward.

Sonamoni Dasi was one of those few female bauls or mendicant singers of the Vaishnava community who sang regularly on this Katoa–Azimgunge route. On this route, these singers liked to call themselves artistes. On the two main routes in the Rarh area—the other being the Bardhaman–Barhaora line—there was too much of a crowd of these rural artistes. Perhaps the main reason for this was that the people of Rarh liked the baul and other traditional folk songs of Bengal very much.

Sonamoni Dasi was a well-known singer in our area. There were many reasons as to why the people travelling by this route preferred her most. Perhaps the reasons were that she possessed good looks in spite of living in extreme poverty, her age was within thirty or thirty-two, her voice was tuneful and she had great control over the beat-rhythm-pitch of the song. Among her countless admirers on this route, I too was one; as were my colleague Rabi, and Malay, the Bengali teacher at Kandra school. Rabi’s fascination was one-dimensional. He had recently been transferred to our office. The first day he had seen Sonamoni, he told me, ‘Did you notice her belly, Issh!’ Hearing Rabi’s ‘Issh!’ it could well be guessed that he then recalled the washer man’s board that could tirelessly endure any amount of beatings or hardships. Malay, on the other hand, could get a mystic feel of infinite renunciation in Sonamoni Dasi’s songs. They were based on the body, body as featured in the Baul philosophy of life. I did not understand any such specificity in myself though. But, it was not that Rabi’s ‘Issh!’ and Malay’s appreciation of Baul philosophy, did not touch me at all. The woman sang well and I liked that. A feeling of partiality rose in me, like a river flooding its banks, whenever I met a woman who sung well; and, if she was Sonamoni Dasi herself, then that feeling soared. What was the meaning of all these then? I felt I was a believer in the theory of Dehatma, the confluence of the soul and the body. Indeed, I was what is called a Dehatmapratyaee or someone who believed only in the union of the soul and the body, to be more exact.

Sonamoni Dasi came near and exclaimed in joy, ‘Jai Nitai! Why are you here, Gosain?’

‘I just got down from the train, as you did. Where have you been, Sonamoni? There has been no sign of you for the last three or four months.’

Indeed, I had not seen her for the last three or four months. This absence had not only been noticed by her admirers, but even by those who never handed out money after listening to her songs. In fact, I too had secretly asked around for her whereabouts from one or two common acquaintances. The person who actually gave me some authentic news was, incredibly, my colleague Rabi!

‘Your pet bird has flown away, Brother.’ There was an envious sting in Rabi’s insinuation.

I couldn’t help falling a prey to his sting.

‘And who is this ‘pet bird’ that you are speaking of, pray?’

‘Sonamoni Dasi, who else? It seems she has flown.’

‘Is that so? Well, where did you get the news?’

‘Why should I tell you? You didn’t tell me that you are a regular at their akhra near the dam on the Ajay river, did you?’ If visiting a place three or four times in a single year at the most, meant going there regularly, then certainly Rabi was right. A few kilometres towards the end of Ajay river, there was a high earthen dam. Ajay had converged with Bhagirathi. Thus, this dam was, in principle, an extension of the dam on Bhagirathi. In the safe seclusion provided by the dams on the two rivers, poor people had built their homes. A woman named Nirmala Dasi had set up an akhra there. The akhra of a poor Vaishnavi in a poor man’s village. But Nirmala had a few devout disciples too. As a result, the floor of the small inner courtyard of the Akhra, fenced off with bamboo-lattice, was smooth and deep red with a neat cement plaster. The fence on the four sides rose atop a three feet brick wall. I had visited this very neat and clean akhra a few times myself. Nirmala was the Guru of Sonamoni Dasi too. That was my attraction for going there. Each year Tushar Pandit of Katoa arranged a few festivals around that area— things like book fairs, cultural fairs, etc. Along with a few other bauls and Vaishnavas, Sonamoni too went there to sing. Though I felt captivated as I listened to her songs in the railway carriages, I had never spoken to her. Once, after listening to her songs in one of Tushar’s festivals, I had remarked, ‘You sing so very well. I listen to them almost every day in the railway coaches. I was pleased when I heard that you would be coming here today.’

Sonamoni had replied, ‘Oh dear! Why do you speak so formally? One who can appreciate a talent is himself talented, isn’t he? He is a Gunamani himself, a gem of talent—as my Guru says. Then why should a Gunamani be so formal? I couldn’t sing much, could I ? Tushar Master has asked us not to sing more than two songs. There are so many artistes here, who would he advance or hold back, tell me!’

To me Sonamoni Dasi seemed as though she was an illustration of the classical Vaishnavis come straight down from the novels 173 of Tarashankar or Bibhutibhushan. Perhaps a bit more. She said, ‘Gunamani Gosain, if you indeed wish to listen to good songs, come to my Guru’s akhra any Saturday. You would surely get to hear some very good songs, I promise you.’

Her experienced eyes could surely discern the fascination in my two eyes. As she called me by a new name, the distraught man inside me who had been captivated by her songs, felt overwhelmed with emotions. And instantly, without thinking, I had replied, ‘Of course I’ll go there someday. Where is that akhra?’

Sonamoni gave me a detailed address. She said, ‘It is in that very place where the river Ajay meets the Ganges. The Vaishnavas have quite a few pilgrim centres there.’

A day before the first day I went to the akhra, I met Sonamoni by chance in the train compartment. I told her, ‘I hope you will be in the akhra tomorrow, won’t you? Then I’ll go there in the evening.’

I had gone there too. Sonamoni’s Guru, Nirmala Dasi, had the look of a grave woman. She was nearing sixty. Many experiences were imprinted on her face, and in her eyes there was an almost other-worldly wariness that forced others to keep a respectful distance. I listened to the songs of three or four artists. Among them many lived only for the songs. The signs of life in those decrepit, wasted figures became conspicuous only when that person held the ektara in his hand and began to sing.

With a dotara in her hand, Sonamoni too had sung four or five songs with the accompaniment of khol and kartals. I had never seen any woman playing a dotara before. Her songs felt fascinating to me.

I too had learnt to play the dotara a little while I stayed in North Bengal.

On my second day at Nirmala Dasi’s akhra, I took the dotara from Sonamoni’s hands. And as I began to strum a few chords 1 on it casually, it seemed as though the tune of a song took shape without even my being consciously aware of it.

Sonamoni listened carefully, and, all of a sudden, she flared out in excitement. Sonamoni exclaimed, ‘Gosain!’ There was something extraordinary in her eyes and the way she looked at me. Those eyes and that look could easily measure you up in a moment with all your considerations. Those eyes could create so much turmoil in you that you would then be in jeopardy. She said, ‘Gosain, talent and song can never be concealed. Sing a song for us.’

The more I tried to make her understand that I did not know any songs, let alone how to sing, the more she became stubborn. And those two eyes of hers that could see even into the remote past constantly searched my face.

At last, I had to sing a song that I had learnt during my stay in North Bengal. ‘Who is so compassionate as my Gosain, there’s no one, no, none at all’—a song that could shake up the very core of a man. At their request I had to sing another song, Lalan Fakir’s ‘It is a strange miracle, a single lamp of beauty burns….’

I had no idea at all of Sonamoni Dasi’s past life. But, after listening to my song, there appeared such an amazement as well as a lustful desire for life in her face and eyes, like the kindling of a wickless light, that could perhaps be explained only by that song by Lalan Fakir. ‘It is a strange miracle, a single lamp of beauty burns within the eighteen homes.’ As though surrendering herself in sublimation, she said eagerly, ‘Would you give this song to me, Gosain? Would you? Tell me, please.’

I replied, ‘This song is by Lalan Fakir. Why, there are many who know it!’

She answered, ‘No, not all know it, in our area no one knows it, none at all.’ Meanwhile, she began to hum it softly to herself, ‘It is a strange miracle—’ and said, ‘And then Gosain? The lines after that?’ And within just half an hour she had learnt the song flawlessly. Then when she sang it with an ektara in her hand, I was surprised to notice that the melody in her voice, as she sang the song, took on a different aspect from the tune and rhythm I had taught her, and became entirely her own. She possessed a good voice by nature, and the song too created and spread a new kind of captivation in her voice.

I wrote the song down in a piece of paper and gave it to Sonamoni. She had had a bit of education too. Afterwards, I had visited that akhra on the dam on the Ajay river again for two more times. Thereafter I began to control myself. I had crossed forty. For many people, especially for those who cultivated their sensitivity through music and dance, paintings and literature, fascination with their object of desire often brought them to the brink of disaster. I had the experience of overcoming a few of such disasters myself and these had boosted my confidence too. But I could no longer tolerate the fluorescence radiating from the two eyes of Sonamoni Dasi. I gradually moved away.

Thereafter I used to meet her only in train compartments. Whenever she boarded the train, she used to look around the compartment; if she could spy me there, she always sang ‘It is a strange miracle—’ and as she got down, the jasmine white, sacred supplication in her slowly waning fluorescent eyes tried to tell me something. I forcibly looked away and fixed my gaze outside the window.

Then she suddenly vanished three months ago. Sometime later Rabi told me, ‘You are a fool. You understand so many things but have no clue about the reality that matters.’

At this time countless thoughts had crowded in my mind. Rabi’s words had many unspoken hints. As I thought about them, an envious suspicion reared its head in my mind. I did not stretch my conversation more with him. But the thoughts never went away. Later, seeing my chance at an opportune moment, I asked Rabi, ‘Did you violate that girl?’

‘Violate!’ Rabi exclaimed as though he was hearing such a word for the first time in his life. Then he laughed out loudly and sneered, ‘Violate! Really you’re so stupid!’

While walking over the railway tracks one had to take longer steps than they normally took. On top of that, the sleepers had been changed on the railway tracks in March–April and new stone-chips had been placed there. One had to be very careful when treading on the stones, otherwise the feet could get cut by the sharp stones. And it was just what happened then. Sonamoni hurt her foot on the sharp edge of the stones. She was wearing a cheap plastic sandal. Blood spurted out from her left toe. She squeezed her foot tightly and sat down right on the railway tracks. The wind was blowing hard. All around was an empty barrenness. The sun gradually matured and became hotter. Just in front, on both sides, was the beginning of a forest that had been planted a few years ago. The woods went on till the head of the Salar station. Trees such as akashmoni, gambil, eucalyptus—all had been planted profusely so as to create a wood in the fallow land that had been abandoned by the railways.

Sonamoni implored, ‘You go on Gosain, or you’ll be late for your office.’ She sat holding her wounded foot tightly. She said, ‘I will walk slowly a little later.’

The Katoa–Azimgunge passenger train whistled loudly from the Salar station. We would have to stand up right now and move aside to let it pass. I said, ‘Let me see how deep the wound is. Come on stand up. Let us go and stand in that wood nearby. The sun is scorching.’

‘No, no, you needn’t see it.’ She exclaimed hastily. But, as she walked down from the rail tracks, I could see her limping visibly. I looked and saw patches of blood at the place where she had been sitting holding her foot in her hands. She went inside the woods and sat down under an akashmoni tree. I too sat down in front, facing her. The wild wood was full of akashmoni trees. Yellow flowers lay strewn all around. I brought out the water bottle from inside my bag and said, ‘Well, bring your foot forward.’

Sonamoni sounded alarmed. ‘Oh dear, you don’t plan to wash my foot, Gosain, do you?’ She hastily hid her wounded foot away under her clothes.

‘Put your foot forward, Sonamoni, or else I will be forced to touch your foot.’

She became a little overwhelmed. Her scared, jasmine-white eyes brimmed over with tears at first, then a carefree, or rather, a childish mischief glinted in her eyes. She brought out her foot in front of me and said, ‘Gosain, who knew that a woman like me would have such a pleasure written in her fate.’

I started to pour water from a little above. The Katoa–Azimgunge train too rushed past us, moving very fast. A few squirrels scurried about here and there and doves flew about with bits of long twigs in their beaks. A cuckoo flew off with a shrill cry from a distant tree and flapping its wings, settled down on another tree nearby. It seemed not a cry at all, but more of a shriek—so loud was it. I was pouring water on to Sonamoni’s foot and I felt that she was gazing at my face unblinking. I could guess too that she was slowly melting.

After I had poured the water, I brought out a small pouch from inside my bag. All men who work outstation like me, keep such pouches with them to carry their shaving kits, things for everyday use and emergencies like combs and brush as well as ointments for cuts and bruises, tablets for diseases like amoebiosis or diarrhoea, even two or three band-aids. I put some ointment carefully on the wound and taped it with a band-aid. ‘Alright, come, drink some water now.’ As I handed her the bottle of water, I realized that my hands were shaking. I noticed too that Sonamoni was leaning against a tree and crying silently. Tears rolled down her cheeks unchecked.

I gave my handkerchief to her and said, ‘Wipe your eyes, Sonamoni. Why are you crying? We are alone in this secluded wood. Come, sing a song now. I haven’t heard your songs for so long now.’

Sonamoni did not take the handkerchief from my hand, she just kept sitting there like that. I wiped her face and eyes with the handkerchief. But still my hands were trembling.

I asked her, ‘Why do you cry? Where were you for so long, leaving us like this?’

In a rasping, broken voice she whispered, ‘I had gone in search of happiness.’

‘Did you find your happiness?’ I asked again.

She took my right hand, held it on her lap and said, ‘My sister’s home is in Bhagabangola. A friend of my brother-in-law was after me for a long time. These three months I had tried my best to see if we clicked. My sister and her husband, that man too, all want me to settle down, rear a family. They want me to stop singing. I have not sung even once for these three months. I had broken my dotara too. But can it go on like this forever, Gosain? Finally, I simply could not adjust anymore and came away.’ Without the least hesitation, I placed my other hand on her lap. I had become jealous at Rabi’s hints. I asked her, ‘Did Rabi, from my office, visit your akhra?’

‘Only to the akhra, you say? He had followed me even to Baharan, to my brother’s place where I lived. He is a gross man, Gosain, he doesn’t want to listen to songs. He had promised to give me much money.’

Once Rabi and I were standing near the door of the train compartment. A young couple stood closely beside the railway line talking to each other. From the running train, Rabi had shouted towards the boy, ‘Arrey! You scoundrel, why do you waste time speaking? Pull her to bed, lay her down without wasting any more time.’

I asked Sonamoni, ‘What do you plan to do now?’ She replied, ‘I will sing and go on as I used to. I will sing songs if I get people like you as my audience.’

‘And your life?’

I felt I already knew what she would say in reply. She replied, ‘Everything is not for everybody, Gosain. You can’t have it all. You’ll be hurt, you’ll cry but still you can’t. There will be poverty and desires, cravings too would be there. They will scorch you, sometimes you will want to be rash, to take risks—’ She fell silent abruptly. At last, she said, ‘But I would have to go on singing songs, Gosain, whatever else happened. I need songs to keep myself alive.’

Suddenly Sonamoni let go of my hands and placed both her hands on my neck. My heart trembled. Our faces were now so close that the distance between them was not even a single foot. All of a sudden, the bird left the nearby tree rending the sky with its shrill cry, and came to sit on the tree on which Sonamoni was leaning. And taking advantage of that tumult, Sonamoni sang out for the first time in three months, ‘Within the eighteen homes burns a single lamp of beauty—it is a strange miracle.’ That song was so emotionally charged that it seemed as embodied as her limbs.