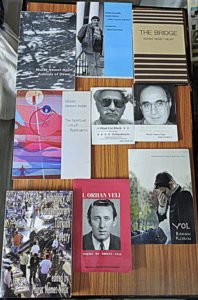

Murat Nemet-Nejat: Poet, Translator, Essayist was born in Istanbul, and has lived in the United States since 1959. His works include a book-length poem, The Bridge, (1977) which is his first volume of poetry that presents the author’s personal battle between memory, family consciousness and the experience in the United States and throws a fresh light on a condition whose cultural shock has become a stimulus for art; The Spiritual Life of Replicants (2011) a book that takes resources from Blade Runner, the film, and according to Efe Murad, “replicates itself as a poem that transcends the confines of its own poetics” , Animals of Dawn (2016) which is according to Maria Damon, “ a radiant matrix of intertextuality…in holding a vast array of precedent texts – as disparate as Hamlet, ‘Un Coup de Des’, and Basho’s famous frog haiku…” and soon-to-be published Io’s Song. His translation works include Eda: An Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry (2004), a book that presents the tradition of poetry hitherto undiscovered by the Western world, I, Orhan Veli, translations of poet Orhan Veli (1989), translation of A Blind Cat and Orthodoxies, a book authored by Ece Ayhan, Rose strikes and Coffee Grinds, authored by Seyhan Erozcelik (2016), and Y’ol by Birhan Keskin (2018). His critical works include The Peripheral Space of Photography (2003) His essay A Questions of Accent, that speaks volumes about the nature of language & identity beyond more orthodox ideas of nativism & foreignness, is one of his most famous, noted works.

Q / A for www.thedreamingmachine.com

Aritra Sanyal: You have been creatively active for three decades as a poet, as a translator, as an essayist. Who of these three basically are you, at the end of the day to yourself?

Murat Nemet Nejat: I am all the three. They feed on each other and form an organic totality. Phrases, passages from my translations (both acknowledged in the text and not) appear in my poetry. My last two poems The Spiritual Life of Replicants and Animals of Dawn are attempts to write American poems using the Turkish poetics of Eda, therefore, injecting that poetics into American poetry. My essays, in essence, always deal with questions that are occupying me, including in my reviews of other poets. For instance, my essay The Peripheral Space of Photography, which I wrote in the 1990’s, explore the relationship between images in photographs and words and how the viewer responds to these images in his or her mind, in words. In that way, the essay accompanies or anticipates my poems: “Vocabularies of Space” (which I wrote about the same time I was writing the essay),The Spiritual Life of Replicants and Animals of Dawn) which I wrote years later. In these poems, the space in which words appear in the poem and the open ended and visual way in which the reader must respond and read them (partly in silence in the mind) are crucial. I can give many more examples.

There is one correction I want to make to your question. I did my first translation in 1960. My life as a poet starts then though these early translations and poems were followed by a writing block that lasted almost ten years. I explain the process in my essay “Questions of Accent“, published first in The Exquisite Corpse in 1993, it can be accessed in its entirety or in selections on line.

AS: You moved to USA from Turkey at the age of 19, if I am not wrong. What seasoned your poetry principally, the American soil or a feeling of exile?

MNN. Definitely, the feeling of exile. When I first arrived in the United States in 1959 to study biology, I felt miserable and terribly homesick. I compensated for this spiritual state by reading Turkish poetry and translating the ones I liked.

AS: In your interview to Jacket Magazine, you said: “The Idea of a Book,” says, “As much as a collection of translations of poems and essays, this book is a translation of a language.” We, in India, would love to know about EDA in details, about the process of translation, and how the idea about a seamless anthology dawned upon you.

MNN: It grew out of the conviction that the twentieth century Turkish poetry was one of the great poetic achievements of that time period. It has an idiosyncratic originality that grows out of the syntactical structure of Turkish language and the implicit Sufi sensibility this syntax expresses, embodies. I wanted the Western reader to read this poetry on its own terms without misreading (and implicitly dismissing it as derivative) through conceptual misappropriations with phrases such as “Turkish avant-garde” (a phrase the English translator and poet George Messo applied to the Second New movement in Turkey), “Turkish Whitman” (the convenient way the poet Ilhan Berk is introduced to the West, an easy phrase that blurs his achievement),surrealism, symbolism, etc. The idea of Eda developed out of this basic concern. Before all, I wanted Eda to represent an Asiatic poetic experiment, speaking to the concerns and arising out of the sensibility, beliefs and thoughts of this continent. For instance, in addition to Sufi ideas, in her recent review of Animals of Dawn, Runa Bandyopadhyay sees in the treatment of time and memory/ oblivion in the poem Hindu/Brahmin connections.

One American book that, in its form, was an inspiration during the writing of the Eda anthology: the anthology The Technicians of the Sacred compiled by Jerome Rothenberg (1969). In this book, Jerome Rothenberg envisions a new experimental American poetry around a group of translations from American Indian, French, Austrian, etc. poetries.

AS: In the same interview you told us that people were shocked at your audacity in not mentioning the contributor-poets’ names in the anthology. It is really something unprecedented. It reminded me of the dynamic relationship which according to T.S. Eliot existed between tradition and individual talent. It seems you preferred to have a panoramic view of the evolution of Turkish literature down the ages. What prompted you to take this fascinating decision: A search for lost time or a fellow feeling about the poets?

MNN: Your description is not quite accurate. I do mention the names and birth and death dates of all the poets whose works appear in the anthology. Also, in a two or three page index at the end of the anthology, I give the Turkish title of each poem whose translation appears in the anthology and the Turkish book or magazine where the poem first appeared in Turkey as well as the date. What I completely omit in the anthology is any additional biographical or bibliographical information besides the birth and death dates, the Turkish title of the poem which is the original source (though my translation, in a few instances, takes quite a few liberties with the original) and the place and date of the original appearance of the poem. That is the audacity that shocked my poet friend Benjamin Friedlander. That bareness of information.

Also, in 2005 after the publication of the anthology, giving a reading from it at the University of Maine, it appears, without my being conscious of it, I was most often not mentioning the name of the poet the translation of whose poem I was reading at the moment, shifting from one translation text to the other with no interjection naming the poet. That is partly what projected the sense of unity of the anthology –that the anthology was not a collection of poems, but each poem, each poet was a station point (in a sense “nameless”) in the progress of a language. The focus was the totality of that language. That is finally what differentiation the book from other anthologies.

AS: I am tempted to ask you about this “progress of language”, as you have seen it, in terms of changing Global and Turkish political scenario. As you have incorporated works of several Turkish poets in this project, I am sure; you have faced a great challenge as a translator in coping with individual viewpoints. Closely related to this is a small question about your own identity as a poet: while translating the Turkish poets, poets sharing a common ethnic identity to which you once directly belonged, what feel did you have: of an “insider’s” or an “outsider’s”?

MNN: I do not have a defined identity in a regular sense as a translator or a poet. Translating a poem I try to be as faithful to the original poem’s essence as I can, though sometimes I need to take liberties transplanting that essence from one language to another. I do not tell lies about the poem or poet I am translating. I am faithful to what I feel is the essence of the poem, though it may exist as a potentiality in the original. My identity as a translator may derive from the texts I choose to translate and the way I read them translating them. My own poetry has very little ‘lyric I’, therefore, identity in that sense. The lyric ‘I’ constantly splits into different perspectives, identities. My focus is on ideas, specific words or multiple voices. I write long poems. My identity derives from the way I connect the different parts, the music of the movement from one part to the other.

The Turkish embodied in Turkish poetry represents my mother tongue. American English is the imperial, non resonant language in which I write/must write. I go into the relation between the two in great detail in my essay “Questions of Accent” . I write in the crack between two languages. Perhaps no poem of mine embodies this reality better than the following poem:

An/kara: My Kind Hearted Step Mother1

Ankara.

An–: moment, second.

kara: black.

Ankara:

Second black, not first.

An(a): mother.

kar: doing it.

kar: snow.

kar(a): to the snow.

kara: land.

kara: black.

K(i)r: prick.

kar(i): the snow.

kari: old crone.

Kirhane: prick house

next to our synagogue in Istanbul there was a prick house,

on wooden tables at the end of Yom Kippur

in the dark, in the intersection of our street and theirs,

the ladies of the night and their pimps left

glasses of water for us to drink

for free: Sebil.

Mysterious Cybil.

So civil-

Ized.

Realized.

thirty years later I went to the same spot.

the synagogue and its porch garden

(where I’d spent two evenings a year, the twinkling lights mixing with the stars through the Succah)

was all in ruins,

the rusting gate ajar,

and a red rooster was strolling at home among the lunar mounds and weeds.

Red rooster: as in red light district?

Red: kizil.

(Kiz): virgin.

(Kiz): angry.

Yuzde yuz kiz: hundred percent virgin.

Yuz: hundred.

Yuz: face.

Yuz: swim.

Rooster: horoz.

Whore

and oz, as in the Wizard of O’s.

- There is a saying in Turkish: Ankara (the capital of modern Turkish Republic) is a wife. Istanbul is a mistress.

AS: Sometimes in your own poems you break a word into halves and this split emanates forces from dimensions that are completely different (like hori…zon…e). I have a few intimate questions about that. A) how does an idea, which you develop into a poem, come to you? Do you see an image? An abstraction? Or simply a word that shines differently with a strange flicker of inspiration? B) how has the process of writing for you changed from the very first day to today?

MNN: My writing process is open-ended. My poems almost always start with a vague image or sense of what I want to do. But I have no idea on how to get there. Then I begin to explore means of achieving that purpose. I write lines and play with them or collect others’ or my own old texts that create the kind of flicker you are referring to. Very often, pursuing where my impulses take me, I digress from my original purpose. I feel lost and become convinced that I will never recapture the sense of wonder and expectation I felt at the beginning. On the average, this process takes about five years. Then gradually, as the poem takes shape, I see the original purpose appear embedded in it. In other words, like a north star, the original purpose guides my work beyond my consciousness; but the means of getting there are totally unexpected, full of contingencies and surprises. For instance, my last poem Animals of Dawn started with my desire to write a work full of explorations at the end of which no answer is found. I wanted to write a poem of the exploration itself in its pure essence. The answer remains in a zone beyond the tip of the hori…zon, so to speak; the bars (or the music that imprisons the angel of chaos) remain. I think the poem achieves that purpose. In the final, ironically climactic “The Ghost Speaks” section, the only thing the speaker achieves is that for an infinitesimally short moment the moss on the bark of a tree in a different time zone become tactile (“COLONIES OF MOSS BECOME TACTILE”).

While the ultimate goal as a vague image was present at beginning, the means of achieving it, the form were almost completely unexpected and a surprise. The idea of using Hamlet came to me some time late in the second year of writing the poem, and at first I resisted the impulse. It was too disruptive. But relatively quickly I realized I had no choice but give in. In the same way, I had no idea that Wittgenstein or Kafka or Levinas would be part of the poem or that its form would be a combination of poems and prose essays or that I would use the kind of puns or word-breaks you are describing. These things happened as a result of my struggle to bring to fruition the original purpose, often accidentally. The Wittgenstein quotes were used by a poet friend of mine, Alan Sondheim, in an on-line discussion during the time I was writing the poem. I combined them with two quotes from Kafka, which I also did on line during the writing of the poem, and one of which I misquote in the poem. I happened to be reading a book, The Burnt Book, about the holy Jewish book of jurisprudence The Talmud during the same time. As my afterword essay “Hamlet and Its Hidden Texts” indicates, the structure of The Talmud has had a strong influence on the structure of Animals of Dawn. That was not part of my original intention, but an opening I came across and followed to serve my purpose. In the same open-ended, opportunistic spirit, I used passages from Turkish poets I happen to translate or passages from my old poems that I retool for a new purpose, etc., etc. I can say the essence of my writing method is letting my instinct of the moment guide me in its meandering rhythm—sometimes into disruptive rabbit holes—and not letting the sense of panic or loss of direction the process creates or the control-freak injunctions of my conscious mind short-circuit the process. I trust utterly that the unconscious totality of my mind knows what is true; that is where knowledge and the poem are buried.

Through the years the process of open-ended randomness remained essentially the same. What has changed is the length of the poems. Therefore, the process of gestation became much longer, Individual poems—which now I hesitate to call poems and call “fragments” or “pieces”—became truly poems when they found their places in a whole. In fact, a significant part of the gestation consists of finding the right place of each fragment in the totality of the poem—exactly where it appears. Also, during the last twenty years or so, space became an integral part of the language of the poem. Therefore, in my writing I open to other media, such as film or photography.

AS: How much do you find editing is important in the process of writing?

MNN: Editing is absolutely essential for me during the writing of the long poems. I experiment with multiple sequences over long periods before I decide on the place of each fragment in the poem. A quite similar process occurs on the placement of lines on a page. This is particularly so in Animals of Dawn where, in multiple instances, I create what I call ‘ideograms’—combining more than one poem, sometimes three or four, each with its own tone or seemingly separate subject, into a single poem on a single page. For such a poem to be successful, the balance of the parts must be exquisitely precise, creating an elusive harmony of thought.

On the other hand, once the poem is written, I almost never change or “re-edit” it. I believe that poem is true for/in that moment when it was written. Re-editing falsifies it, introducing (while ignoring) the element of time. In that way, it is deceptive like memory. It remembers the poem incorrectly. Quite often, I deconstruct and re-write an old poem, or a part of it, to place it in a long later poem. Re-written, in that new framework, one has a new poem separated from the older one by the element of time. One has a poem altered by time. Neither better than the other.

AS: Poems utilize the weight and effect of the words, but more importantly, reading you one may think logically think over the role of ‘space’ in poetry, sometimes ‘eloquent’ space and sometimes ‘space’ in the sense of ‘Silence’… can we know your opinion?

MNN: Silence can be most eloquent. As Keats says, “heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard sweeter.” For me emptiness is the space of the politically and psychologically suppressed, of the “unreal.” The eloquence of language uttered through its silence escapes syntactical rules. It becomes, in poetry, a tabula rasa of rebellious, subversive thought—a space of freedom and imaginary.

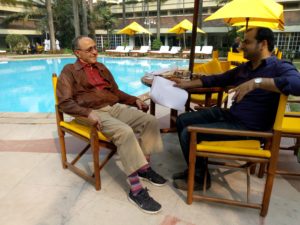

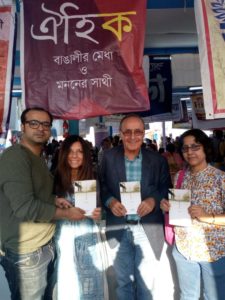

Gallery of Murat Nemet-Nejat and literary co-conspirators in .Kolkata

Aritra Sanyal is a poet, translator, researcher, and an ex-sports journalist who presently works as a teacher of English language in a school in West Bengal, India. He is a doctoral candidate at Assam University focusing on the novels of Amitav Ghosh. Earlier he worked as a research fellow in University of Calcutta under the supervision of Prof Chinmoy Guha in a major research project: Impact of France on the 19th an early 20th Century Bengali Literature. He is the author three books of poetry. Forthcoming is Ekta Bahu Purano Nei (An Old Absence) from Pathak Press, Calcutta.

Photos by Aritra Sanyal.

Comments 1